Taiwan in Time: Aug. 1 to Aug. 7

At the end of World War II, the Taiwanese in Beijing got together and celebrated the defeat of Japan, which had colonized Taiwan in 1895 and conquered much of East Asia in the 1930s and 1940s.

Beijing fell to the Japanese in October 1937, and as Japanese citizens, many Taiwanese traveled there to work. Official Japanese records show that between late 1937 and early 1944, the Taiwanese population increased from 37 to 548. The majority of them worked for the Japanese as minor officials and translators or as Japanese language teachers in local universities.

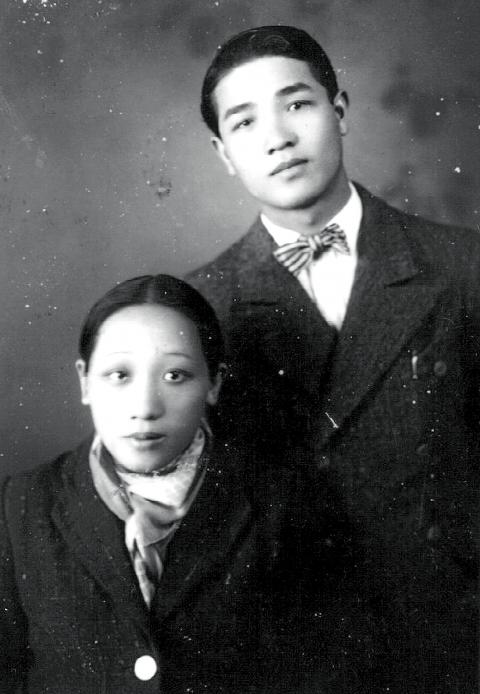

Photo courtesy of Chung Li-ho Literary Memorial Museum

After the war, those Chinese officials that ranked higher than county commissioner under the Japanese were deemed traitors and punished. Most Taiwanese did not qualify, but many lost their jobs and were seen as traitors by the Chinese anyway — finding it necessary to hide their Taiwanese identity.

Pingtung native Chung Li-ho (鍾理和) was deeply disturbed by this treatment, noting that he had happily celebrated when the Japanese surrendered. After no Chinese official showed up at the Taiwanese in Beijing Association’s formal celebration, Chung wrote the short story, The Sorrow of the White Sweet Potato (白番薯的悲哀).

“They were cast aside by the motherland,” he writes. “They wanted encouragement, comfort, warmth, the gratitude of a long-awaited reunion — but there was nothing. The white sweet potatoes walked out of the celebration feeling empty, disappointed and miserable.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

He says that they were “excluded from the motherland’s glory” because of history, because they were once citizens of the enemy.

“Beijing is large,” he writes. “Its greatness and humility can embrace everything within — but if someone finds out that you’re Taiwanese, unfortunately, that equals a death sentence. Then, you will start feeling that Beijing is cramped — so cramped that it cannot hide you anymore.”

Chung swore not to return to Taiwan when he first arrived in China eight years previously, but in March 1946, Chung, his pregnant wife and their son boarded a refugee boat to Keelung, arriving in his family home in Meinong District (美濃) in today’s Kaohsiung later that year.

Chung and his literary contemporary Wu Cho-liu (吳濁流) both wrote about the identity crisis of Taiwanese during World War II, being distrusted by the Chinese in the “motherland” and discriminated against by the Japanese at home. But while Wu sought a new life in China after being fed up with discrimination, Chung fled Taiwan in the name of love.

Born to a wealthy family, Chung was always fascinated with China, which he calls the yuanxiang (原鄉, original or old country), through listening to his father talk about his travels after business trips to China. When Chung’s brother returned from a trip to China, they listened to records and marveled at scenic photographs. He writes in his novel, From the Old Country (原鄉人) about his experiences with people from the old country, starting from the private Chinese-language school he attended to various peddlers he would meet, developing a generally positive impression.

“I’m not a patriot, but the blood of one from the old country will not stop boiling until he returns to the old country,” Chung proclaims in the novel.

After graduating from a Japanese school, Chung spent a year and a half learning Chinese, before later finding work on his father’s farm in Meinong. There, he fell in love with farm worker Chung Tai-mei (鍾台妹), but their union was met with disapproval because they shared the same surname. Chung severed relations with his family and fled to Shenyang in 1938, which was then under Japanese control, and came back to elope with his lover in 1940.

“Unless you’re very naive, you would never expect your father to risk his reputation to hold such a wedding for his son,” he writes in the novel Lishan Farm (笠山農場), which is based on this incident. “Maybe young people see glory and greatness in being a revolutionary, but no father would want his son to start a revolution.”

Chung asserts his unwavering belief in fighting one’s fate in two other novellas. In Weak Breath (游絲), he tells the story of a woman whose father tries to force her into an arranged marriage, detailing her struggle between accepting fate or fighting for what she really wants. And in Silver Grass (薄芒) he details the tragic results and sacrifices people make when they obey traditional values over their own desires.

“People are willing to accept this cup of bitter wine, tears streaming down their face, saying that this is fate,” he writes.

Indeed, Chung was a true idealist, choosing to live in poverty over working for the Japanese, writes literature professor Chen Chao-chen (陳兆珍) in her book, A study of Chung Li-ho’s Thought and Work (鍾理和思想及其小說研究). And despite being mostly educated in Japanese, he insisted on writing in Chinese. It is not hard to imagine his dismay when he was forced to return to his homeland where he still “had memories of past sorrow.”

Chung writes that he developed tuberculosis during his 20-day journey on the refugee boat with not enough to eat or sleep.

He worked as a Chinese teacher for a while, but quit due to his illness. The final 10 years of his life would be his most prolific period as an author, but it was not easy. Living in poverty after exhausting the family’s resources, his older son developed a disability due to illness and his younger son died. He was still looked down upon by the community due to the taboo he violated, and his brother and his closest childhood friend were executed during the White Terror era. One bright spot was Lishan Farm winning a national literary award in 1956.

Legend has it that Chung kept writing despite his illness, and died after coughing blood onto a manuscript, earning him the moniker “The Writer who Lies in a Pool of Blood (倒在血泊中的筆耕者).”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand