Kick-wheel potter Chan Kuo-hsiang (詹國祥) tells a story of how late president Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國) was puzzled during a visit to the old pottery town of Yingge (鶯歌鎮). BMWs and Mercedes were parked along streets lined with dilapidated buildings — conspicuous wealth amid ramshackle abodes.

Before China opened up its market, Yingge potters producing imitation Chinese ceramics were raking it in.

“The heyday was probably 1980 to 1990,” says Cheng Wen-hung (程文宏), head of the Educational Promotion Department of the New Taipei City Yingge Ceramics Museum. “After that... most of the big factories moved to China.”

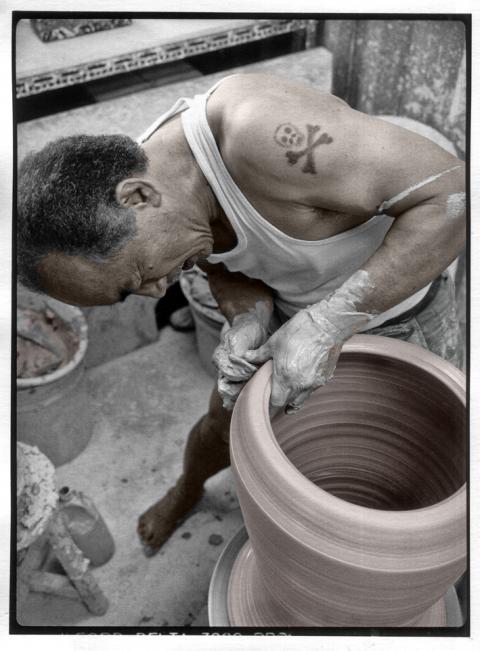

Photo: Paul Cooper, Taipei Times

Chan and his brother, Weng Kuo-hua (翁國華), specialize in throwing huge pots. They have seen good times and bad. In many ways, their fortunes have been tied to those of Yingge itself.

Yingge has been a pottery town since 1804. It flourished because of local coal and clay deposits, and, later, because the arrival in Taiwan of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in 1949 put a temporary stop to pottery imports from Japan and China. This gave Yingge potters the chance to start producing functional wares for the domestic market.

IMITATING DYNASTIC PORCELAIN

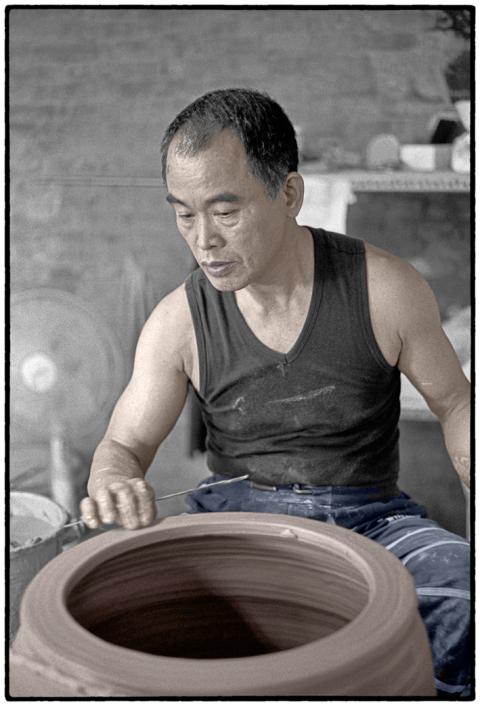

Photo: Paul Cooper, Taipei Times

In the 1970s, many factories also started producing imitation Chinese imperial wares. Experts from Hong Kong were brought over to introduce traditional Chinese ceramics techniques. Many of the wares were exported, and some were sold as authentic Song, Yuan, Ming and Qing porcelains.

For a time, there was money to be made, with imitation wares being sent to Hong Kong, Japan and the West. Yingge had moved from its humble beginnings to become a major exporter of quality wares.

Chan and Weng were born in Yingge, but their father, a kick-wheel potter making large water jars in the town, moved the family to Miaoli in search of work when they were still little. The family was too poor to afford rent. The boss was kind enough to let the whole family live in the factory. The brothers lived there until they were 20.

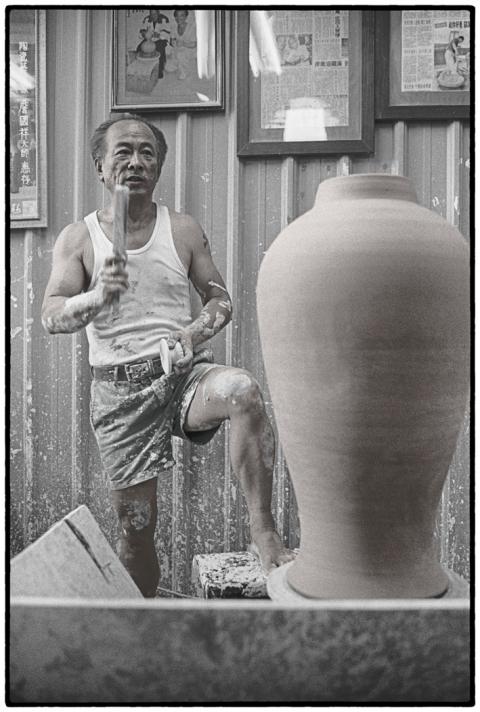

Photo: Paul Cooper, Taipei Times

Being constantly around the factory for their entire childhood, the brothers were able to learn their craft — learning the techniques of coiling and throwing on the kick-wheel, the traditional potters’ wheel introduced by the Japanese and used in Taiwan before the invention of an electric version.

Weng started learning properly when he was around nine or 10, working at the factory at around 16 or 17.

“I was very skilled at this point, since I had started very early.” he remembers.

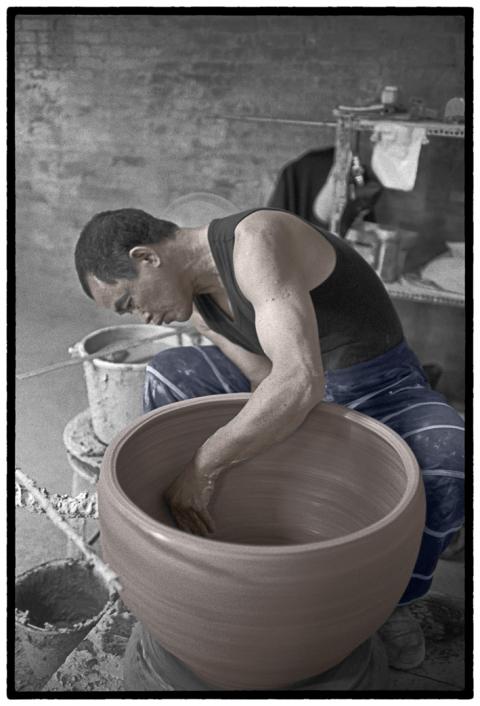

Photo: Paul Cooper, Taipei Times

During the heyday, Weng took off on his own and developed his own crystal glaze over many years of experimentation. He would decorate his own pots with this glaze, and sell them in shops around Yingge.

“It would cost me NT$50,000 to make one piece. The shop would place a heavy commission on top of this, charging say NT$300,000,” Weng says.

Weng remembers turning his own house into a factory, to fit in all the large kilns he needed, and having no space left in which to sleep.

Photo courtesy of Chan Kuo-hsiang

“I was nuts. I spent all my money on the kilns and on making the pots,” says Weng. “I could have bought a lot of houses for that money.”

MARKET CHANGE

Then the market changed. Cheng says that increased investment in China led to a steep decline in the number of people employed at factories in Taiwan. Only a few people work in the factories producing imitation wares nowadays.

Weng had to abandon his creative work in 1996. He drove a truck, delivering electrical goods around Taiwan, from ages 43 to 53. He returned to Yingge 10 years ago to work in a factory again.

You won’t see so many luxury cars in Yingge nowadays. Much of the creative work has moved out of town, where people work in smaller studios.

Chan has his own factory now, making large pots to order. He also introduces the kick wheel technique every week at the museum, hoping to keep the tradition alive.

Weng works in a factory. He still coils water jars. He has plans of making more creative work again, resurrecting his crystal glaze. Unlike his brother, he is not very positive about the possibility of passing on their traditions.

“There is a good reason the younger generation don’t want to do this kind of work, not if they don’t come from a rich family. There’s simply no money in doing it at a creative level,” Weng says.

Next month, Tseng Tsai-wan (曾財萬), also known as Master Wan, who shows that locally-produced quality wares still have a place in a fiercely competitive market.

Yingge Town Artisan is a monthly photographic and historical exploration of the artists and potters linked to New Taipei City’s Yingge Town.

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not