Hot on the heels of the success of his debut novel, The Teahouse of the August Moon, American author Vern Sneider spent the summer of 1952 in Taiwan researching his next book.

Ushered in by the 228 Incident of 1947, the White Terror era was at its most brutal at that time as thousands of suspected political dissidents were imprisoned or executed by the ruling Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT).

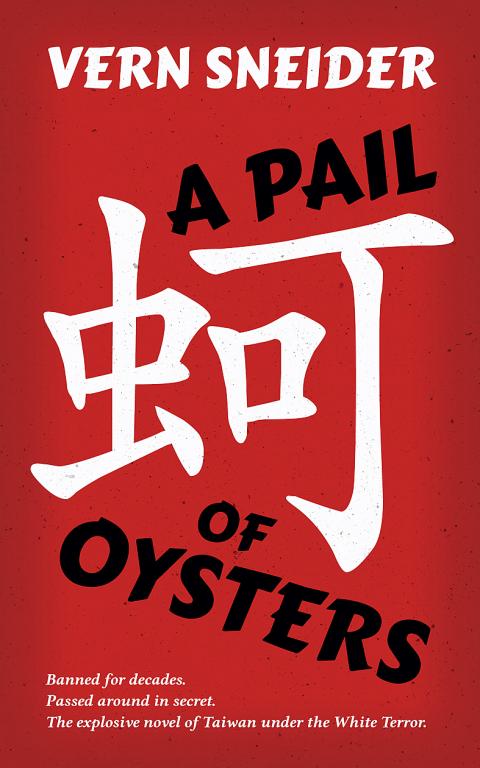

The resulting book, A Pail of Oysters, was banned in Taiwan, but to Sneider’s dismay, even the US denounced it. It was the McCarthy era, and anything portraying the KMT in a negative light was inevitably painted as pro-communist. It went out of print shortly after.

Photo courtesy of camphor press

While Mandarin and Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) translations have been available since 2003, English editions are rare (rumor has it that pro-KMT students hunted down and destroyed copies from US libraries), with Abebooks.com just listing six copies, ranging from about NT$900 to NT$3,800.

“It’s one of those books that were passed around in secret during the bad old days,” Taiwan and UK-based Camphor Press cofounder Mark Swofford says.

Camphor Press is today releasing the first republishing of the book since the 1950s in digital format, with a print edition to come soon.

“It was suppressed and never got a fair hearing. We want to give it one,” Swofford says.

The book depicts life during White Terror through a variety of characters — most prominently Li Liu, a half-Hakka and half-Aborigine whose family is robbed by KMT soldiers at the beginning of the novel.

But bashing the KMT isn’t the point of the novel, Swofford says.

“It’s a very complex novel, [written] when many people thought it was just the communists versus the KMT,” he says. “It was more of a middle way sort of thing; from the standpoint of the Taiwanese people.”

RE-INTRODUCTION

Late last year, Jonathan Benda, a lecturer at Boston’s Northeastern University, found himself interviewing Sneider’s 85-year-old widow, June.

Benda was familiar with A Pail of Oysters. He read it during his 18-year stay in Taiwan and published an academic paper on it in 2007. Benda says he had once considered republishing it, but lacked the means to do so — and was surprised when Camphor Press asked him to write the introduction to their new edition.

Benda was eager to learn more about the book. In addition to speaking to June, he also dug up old articles and correspondences and obtained copies of the author’s notes through his hometown museum in Monroe, Michigan.

Stationed in Okinawa and Korea, Sneider had never been to Taiwan before the summer of 1952, but the US Army had him study the country at Princeton University in preparation for possible military occupation during the war.

Benda was impressed with the amount of research Sneider’s notes contained — including interviews with people ranging from then-governor K.C. Wu (吳國楨) to pedicab operators and extensive notes on items such as how children are named and blind masseuses. He even had his palm read, which is featured in the novel.

“It’s easy to point out mistakes or problems with his depictions … but I come away thinking that he got a lot of it right,” Benda says.

Through examining letters, Benda found that Sneider had hoped to counter the pervading pro-KMT perception of Taiwan as “Free China” and show how its people were actually suffering under martial law.

“My viewpoint will be strictly that of the Formosan people, trying to exist under that government,” he wrote to George H. Kerr, author of Formosa Betrayed. “And … maybe, in my small way, I can do something for the people of Formosa.”

But although Sneider was critical of the government, he generally gives a balanced picture, including democracy proponents in the KMT and sympathetic soldiers, Benda says.

In addition, the American perspective is shown through the eyes of Ralph Barton, a journalist investigating life in Taiwan under martial law — which corresponds to Sneider’s role, except that the author believed that fiction is a more powerful vehicle through its “emotional pull,” as detailed in his letter to Kerr.

Sneider died in 1981 — too early for any chance to redeem his book, but at least June is able to see it happen.

“She was glad to have this out during her lifetime,” Swofford says.

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name