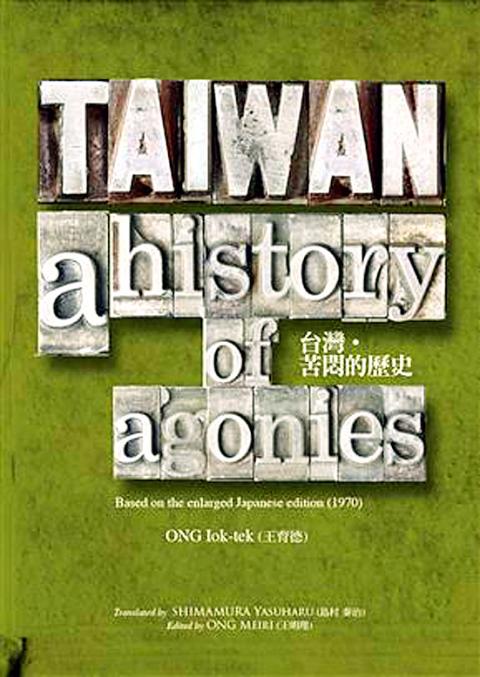

Ong Iok-tek’s (王育德) Taiwan: A History of Agonies has finally become available in English. Originally written in Japanese and translated into Chinese, its long-awaited English translation was completed last year. For that reason, Ong (1924—1985) may not be a household name among many in the West who study Taiwanese history, but that does not diminish the valuable insights and contributions of this work.

To place Ong in context, he was born in Taiwan in 1924 during the Japanese colonial era, and was a contemporary of Su Beng (史明, b.1918), a historian and Taiwan independence advocate, former president Lee Teng-hui (李登輝, b. 1923) and democracy pioneer Peng Ming-min (彭明敏, b. 1923), all Taiwanese who studied in Japan.

Parallels can be found between Ong’s book and Su Beng’s 400 Years of Taiwan History. Both books were originally written in Japanese. Su’s 400 Years was written in 1962; Ong’s History of Agonies in 1964. Both were later translated into Chinese and would be instrumental in informing Taiwanese of their past. Ong’s book was translated into Chinese in 1977; Su’s was translated in 1980. Su’s book would further be translated into English in 1986, whereas Ong’s English version was published last year.

Su and Ong both fled to Japan where they moved in different circles. Ong returned to his studies in 1949 and went on to get a doctorate in literature at the University of Tokyo; he would work with developing Taiwan support groups in intellectual and international spheres. Su escaped Taiwan in 1952 and would continue as a revolutionary, training insurgents to return to Taiwan.

Ong’s book is for those researching Taiwanese consciousness post-WWII. What makes it unusual is not just the historical content, much of which can now be found in other contemporary works, but the realization that awareness of Taiwan’s history and identity had reached a state of maturity in Japan by 1964.

Taiwan of course was under martial law and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) controlled most discourse coming out of the nation to the English-speaking world. In 1964, Peng was arrested on charges of treason for his pamphlet Declaration of Formosan Self-Salvation. In the following year, Lee left Taiwan to study for a doctorate at Cornell University.

While in Japan, Ong kept close tabs on Taiwan-related issues, including Peng’s house arrest and later escape. In Ong’s update of 1970, he devotes several pages to Peng’s ideas and flight to Sweden. Ong’s daughter, who helped in making the English version available, stresses that her father’s lifelong aim and pursuit was, “Taiwan is not China. The Taiwanese are not the Chinese. Taiwan should be ruled by Taiwanese themselves.”

Ong’s attention to detail and his ability to draw from Japanese periodicals and other sources are added benefits. Some may be familiar with the Qing Dynasty adage: “an uprising every three years and a revolution every five years.” Ong provides a list for each uprising and revolution, including the year, names of important people and the consequences.

Ong also provides the name, position and background of over a dozen Taiwanese who were targeted and murdered during the 228 Incident and its aftermath, including his brother who was a prosecutor in the Hsinchu District Court. Ong also writes how Taiwanese later were aware that Communist China and the KMT, though at odds, were united in their efforts to suppress any suggestions of Taiwan independence

As Ong spent the final 36 years of his life in Japan, one comes to realize the extent to which Taiwanese consciousness and the support of the independence movement was housed there throughout the 1950s and 1960s. It would later shift to the US in the 1970s and 1980s as more Taiwanese did their graduate studies there. Ong was involved with these different groups and was instrumental in setting up the “Taiwan Youth Society,” which was the forerunner of World United Formosans for Independence.

The book’s preface and final chapter were added by Ong’s daughter to take it well beyond Ong’s 1970 update. She also adds a timeline which ends with the KMT’s overwhelming loss in the November 2014 nine-in-one elections.

The translation reads extremely well. Since most of the book was written in 1964 and updated in 1970, the work uses the Wade-Giles system of Romanization. One can also expect a few discrepancies in historical dates and perceptions that would be cleared up in later decades as more information became available.

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,