Taiwan in Time: Feb. 22 to Feb. 28

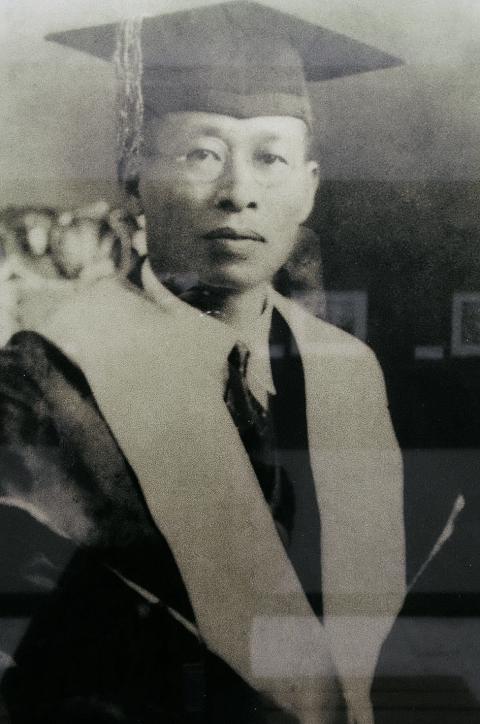

On the evening of March 11, 1947, as Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) reinforcements from China clashed with local protesters throughout Taiwan, Lin Mo-seng (林茂生), founder of the Minpao (民報) newspaper and dean of liberal arts at National Taiwan University, was reportedly escorted from his family home by six men, never to be heard from again.

As the first Taiwanese to receive a Doctor of Philosophy degree, Lin was one of many intellectuals targeted by the China-based KMT government during its violent suppression following the 228 Incident, which began as an armed local uprising. A large number of Taiwan’s private newspapers, which sprung up after Japan’s surrender in August 1945, were shut down within two weeks of the initial incident, including Lin’s Minpao.

Photo: Meng Ching-tsu, Taipei Times

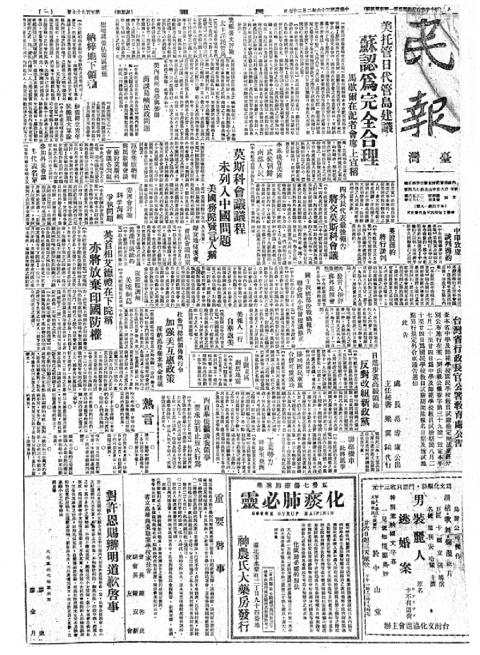

Not to be confused with the Japanese-era Taiwan Minpao (台灣民報), Lin’s paper made its debut on Oct. 10, 1945. Never afraid to criticize the government and including a column for citizen voices, it quickly became the most widely read private paper.

A quick sample of editorials during its brief existence shows titles such as “Are the People of Taiwan Really Happy?,” clearly reflecting the rising tension between local inhabitants and the newcomers from China.

One editorial, printed on July 24, 1946, even goes as far as stating that government corruption and nepotism is a “bad habit from the motherland that is now being picked up by Taiwanese.” It is not too hard to see why he would have upset the KMT.

Photo courtesy of National Library of Public Information

Interestingly, no institution in Taiwan appears to possess any record of this newspaper past Feb. 28, 1947, even though most sources have it printing its last issue on March 8, three days before Lin’s arrest.

The only reports available during the incident in the National Central Library’s newspaper archives are from the Taiwan Shin Sheng Daily News (台灣新生報), which was the official publication of the Taiwan Provincial Government, and the KMT-run China Daily News (中華日報).

The book, Lin Mo-seng, Chen Hsin and Their Era (林茂生, 陳炘和他們的年代) details Lin’s final days, as told to author Lee Hsiao-feng (李筱峰) by Lin’s son, Lin Tsung-yi (林宗義).

The younger Lin recalls his father responding to the incident, saying “Taiwanese are ready to tell the Mainlanders that we have had enough of being treated as second-class citizens, and we have had enough of authoritarian rule and government corruption that has been going on since October 1945.”

But Lin also denounced the use of force against the government, warning that violence is an ineffective method that would lead to disastrous results.

“The key to our future is democracy and respectful relations between Taiwanese and Mainlanders. We [Minpao] still face a momentous task in front of us,” he adds.

On March 4, after meeting with the 228 Incident Resolution Committee, Lin lamented to his son that this uprising lacked clear leadership and organization and that it was going nowhere.

The next day, Lin’s Japanese friend warned him that he was in danger. Even though Lin didn’t overtly participate in the uprising, he and his newspaper’s influence in society already posed a threat to the KMT.

On March 8, Taiwan governor Chen Yi’s (陳儀) reinforcement troops landed in Keelung as the government rejected all 32 demands made by the resolution committee, and the crackdown became increasingly violent. Minpao’s office was destroyed that night.

Lin Tsung-yi was notified by a servant of his father’s arrest in the morning of March 11. When Lin Mo-seng’s wife asked the men where they were taking him, one of them reportedly replied, “We’re going to see Chen Yi.”

Official charges against Lin included plotting rebellion, encouraging [NTU] students to riot and attempting to use international interference to achieve Taiwanese independence.

Most historians agree that the real reason Lin was arrested was because of his newspaper’s criticism of the government. And it was not just Lin.

The publishers of other private newspapers, such as the People’s Herald’s (人民導報) Wang Tien-teng (王添?) and Ta Ming Pao’s (大明報) Ai Lu-sheng (艾璐生), were also taken away never to be seen again.

But the most curious part of this is that even Juan Chao-jih, (阮朝日), general manager of the government’s Shin Sheng Daily News, became a victim of this media purge, together with editor Wu Chin-lien (吳金鍊) and other staff members.

On March 25, the Shin Sheng Daily News announced its new general manager and editor-in-chief, who were high-ranking military and government officials.

What happened to these people and how the newspaper’s coverage changed under the new management will be examined in next week’s edition of “Taiwan in Time.”

Part II appears in next Sunday’s Taipei Times.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand