Nils Frahm does some very interesting things with the piano — or to be more exact, with four pianos. For his stage performances, he currently uses a grand piano, an upright piano, a Fend Rhodes electric piano and a Juno synthesizer, jumping from one instrument to another, sampling and looping their sounds through a computer and creating engrossing compositions with a very broad appeal.

Frahm is not only making a splash in the staid world of contemporary classical, but also drawing hoots and hollers from young listeners who otherwise identify more with electronic dance music or indie rock.

This autumn, the 32-year-old German will tour to some of the world’s best known concert halls. He has already sold out October shows in the Sydney Opera House and the Barbican in London and will play a wide variety of other stages, including churches, contemporary art centers and arts festivals in Europe, Australia and North America.

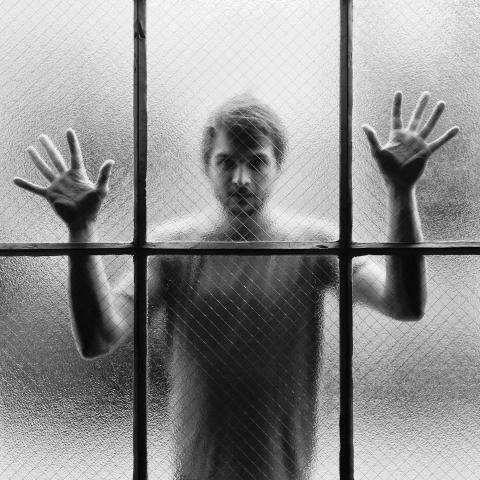

Photo courtesy of White Wabbit Records

Frahm’s only performance in Asia will be Saturday in Taipei in a warehouse converted to an indie rock live house, Legacy. The concert will open up the P Festival — the “P” is for “piano” — a two week series of performances by contemporary pianists including international names like Frahm, Rachel Grimes and Hauschka along with local cross-genre standouts like Lu Yi-chih (盧易之) and Cicada.

ACCESSIBLE SOUND

Photo courtesy of Legacy

Frahm’s music is by turns complex, emotional and widely accessible. It can at times be extremely down to earth and even quite funny, like his recent composition, Toilet Brushes — More, which begins with Frahm banging directly on the strings of an open grand piano with the titular bathroom cleaners. (There is a fantastic video of a performance of the work at London’s St John-at-Hackney Church on YouTube. Frahm is a big fan of YouTube and quickly uploads videos of many performances to the site.)

The idea to use toilet brushes was fairly spontaneous.

“When you go to IKEA you always buy a lot of crap you didn’t intend to,” says Frahm, speaking over the phone from his studio in Berlin. “I was browsing and I saw the toilet brushes, but they were only selling them in a pack of two. That didn’t make any sense to me, because I think that most people who buy things at IKEA don’t have two bathrooms ... So why would you need to buy two toilet brushes?”

Photo courtesy of Legacy

Frahm notes, however, that the toilet cleaners “looked like drumsticks to me, and I thought, ‘Okay, now I know why I need two of them.’”

He says he took the brushes directly to a gig and used them instead of musical mallets.

“What interested me was seeing the ridiculousness of what I’m doing paired with the grandness and hugeness of the sound it produces. The sound is kind of sinister and sincere. By having to laugh while listening to something really dark — it creates a nice tension in the concert,” says Frahm.

“It’s like defining the borders of my universe. On one side I have that kind of lighthearted, goofy, jokey elements, which is just part of my persona. I’m making these silly jokes between songs and so forth. But then two minutes later, you are listening to something heart-breakingly sad and tragic, musically.”

The toilet brushes may be a quirky innovation, but it should not be confused with mere noise or other types of abstract or experimental music.

Each piece by Frahm is conceived very much as a composition, and works manage to synthesize ideas from traditional chamber music, medieval music, avant-garde 20th century composers like John Cage, Steve Reich and Terry Reilly and also contemporary rock, pop and electronic music, which composes much of “the couple thousand records in my record collection, which I love.”

Frahm’s more fundamental purpose in using the toilet brushes was to pull some percussive sounds out of the piano. Because even though he uses electronics, he believes the sounds he produces must all be produced by him playing the actual instruments, even if those sounds are later looped or modulated by delays or other electronic effects.

“It’s obvious that all the motions and movements I’m doing are connected to the sound, and that’s kind of exciting for people to watch, rather than just have an iPad and pressing play. Then there is this big wall of sound and you play piano on top,” he says.

“I’m struggling for sounds,” Frahm adds. “Since I’m not using a computer, which can reproduce twelve million sounds, I’m using a limited set.”

The limitations of the piano’s sonic palette also got Frahm to start using a synthesizer in his concerts about two years ago.

“I was playing only piano concerts, and I felt I needed a very loud element between sections, so that the surrounding songs would feel different,” Frahm explains.

“You have to know what comes before a certain passage determines that passage. For me it’s very important that a concert flows from start to finish, and that one song helps another song become stronger by putting them in the right direction.”

It also amounts to an exciting new direction in music. You can hear it for yourself this weekend in Taipei.

Nils Frahm plays with Lu Yi-chih (盧易之) on Saturday at Legacy, 1, Bade Rd, Sec 1, Taipei City (台北市八德路一段1號). Tickets are NT$1,650 through www.artsticket.com.tw. P Festival runs from Oct. 4 to Oct. 19. For more info: www.pfestival.tw.

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand