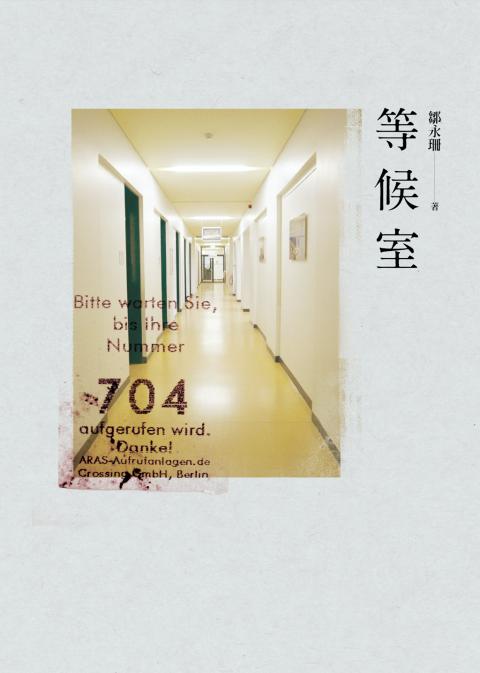

The life of Hsu Ming-chang (徐明彰) has dropped to a new low. He’s in Berlin, unable to appreciate its cultural riches, reeling from his divorce from a career woman for whom he had left Taiwan. His only source of income is freelancing for a Chinese-language publication. He speaks little German. Worse yet, his visa has expired, so he must make a trip to the waiting room of the Foreign Registration Office, where dreams are made and crushed with the same sterile detachment.

The Waiting Room (等候室), the Chinese-language debut novel of Tsou Yung-shan (鄒永珊), picks up at this juncture to follow Hsu as he navigates his visa troubles and the streets of Berlin.

Tsou, trained in mechanical engineering at National Taiwan University, is a new voice with an eye for fleeting detail. She picks out the tiny things that set Berlin apart, like how homeless men keep dogs, and renders them with a light and no-nonsense prose. She’s also expert at depicting the special miseries of the displaced person, such as the downgrade in social class, or how things that never cost a cent before are now painfully expensive — for instance, deep silences with a loved one over a pay phone. That’s Hsu calling his mother, of course — his ex-wife is back in Taiwan but doesn’t want to chat — and every expensive session leaves him feeling increasingly alienated from his home country.

Is his true home in Berlin? The question is open as Hsu struggles along in a foreign land, enrolling in a German class and cooking for himself for the first time. In another unprecedented move, he recoils from a series of bad housemates and springs for a little studio, the first personal apartment of his 32-year-old life.

The Waiting Room is clearly his bildungsroman, but he interacts with the locals, too, and eventually Tsou expands the stories of key auxiliary characters, all whom prove loosely connected to the Foreign Registration Office. Some, in their own ways, are alienated just like Hsu. There’s Mrs. Nesmeyanova, an immigrant from Minsk who becomes his landlady and housemate. She wants to leave Germany and go home, but can’t on account of an overbearing husband. Then there’s Ms. Meyer, an overweight and socially isolated German national who handles his visa request. Hsu feels put out because she treats him mechanistically like a number, as if that were a uniquely German thing. But it’s a people thing — unwittingly, he does the same thing to her, never learning her name and thinking of her, when the dreaded occasion requires it, simply as a fat German lady.

It’s with the cast of side characters that Tsou loses some of her gift for intimate details that build to match an absurd and unexpected reality. The weakest moments in the book are when Hsu meets, at separate times, a character named Christian and another named Christina and neither named Jesus, though they may as well have been for their weirdly wise dialogue and the tonic effect that it has on him.

Christian is a German who moves into the same building and listens to music turned up too loud, irritating all his neighbors except Hsu, who’s only intrigued. The two of them become friends and eventually lovers, and Christian teaches him that it’s not all right to let German phone companies scam him and that it is all right to ask for help.

Christina is a third-generation German Turk who meets Hsu by chance at her art exhibition at the Foreign Registration Office. She has thought a great deal about her identity as a German and as an ethnic Turk, which is believable, but her monologue — composed and grand like a personal statement for graduate school in sociology — is not. Despite that, their encounter is good for Hsu, who realizes that he is just like her, a thing caught between here and there. “Don’t be afraid. Chin up, back straight,” Christina concludes, unknowingly repeating Christian’s words of counsel, in one of the more aggressively placed coincidences of the novel.

At this point the plot is awkward, but it is an unusual disruption from a mostly elegant narrative. In a way, Christina performs a service, leading the reader to clumsily zoom out above the minutiae of Hsu’s life, so that his story is not exactly the story of a Taiwanese man, but a hopeful narrative about someone who learns to be comfortable with feeling uncomfortable. Perhaps, Christina/Tsou suggests, so long as people continue to grow, where home is will continue to be an open question.

The Waiting Room, a recommended title in this year’s Taipei International Book Exhibition, won a translation grant from the Taipei Book Fair Foundation and is being translated into English by professor Michelle Wu (吳敏嘉) of National Taiwan University’s Department of Foreign Languages and Literature. The work is scheduled for completion this year.

The Taipei Times last week reported that the rising share of seniors in the population is reshaping the nation’s housing markets. According to data from the Ministry of the Interior, about 850,000 residences were occupied by elderly people in the first quarter, including 655,000 that housed only one resident. H&B Realty chief researcher Jessica Hsu (徐佳馨), quoted in the article, said that there is rising demand for elderly-friendly housing, including units with elevators, barrier-free layouts and proximity to healthcare services. Hsu and others cited in the article highlighted the changing family residential dynamics, as children no longer live with parents,

The classic warmth of a good old-fashioned izakaya beckons you in, all cozy nooks and dark wood finishes, as tables order a third round and waiters sling tapas-sized bites and assorted — sometimes unidentifiable — skewered meats. But there’s a romantic hush about this Ximending (西門町) hotspot, with cocktails savored, plating elegant and never rushed and daters and diners lit by candlelight and chandelier. Each chair is mismatched and the assorted tables appear to be the fanciest picks from a nearby flea market. A naked sewing mannequin stands in a dimly lit corner, adorned with antique mirrors and draped foliage

Oct. 27 to Nov. 2 Over a breakfast of soymilk and fried dough costing less than NT$400, seven officials and engineers agreed on a NT$400 million plan — unaware that it would mark the beginning of Taiwan’s semiconductor empire. It was a cold February morning in 1974. Gathered at the unassuming shop were Economics minister Sun Yun-hsuan (孫運璿), director-general of Transportation and Communications Kao Yu-shu (高玉樹), Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) president Wang Chao-chen (王兆振), Telecommunications Laboratories director Kang Pao-huang (康寶煌), Executive Yuan secretary-general Fei Hua (費驊), director-general of Telecommunications Fang Hsien-chi (方賢齊) and Radio Corporation of America (RCA) Laboratories director Pan

The election of Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) as chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) marked a triumphant return of pride in the “Chinese” in the party name. Cheng wants Taiwanese to be proud to call themselves Chinese again. The unambiguous winner was a return to the KMT ideology that formed in the early 2000s under then chairman Lien Chan (連戰) and president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) put into practice as far as he could, until ultimately thwarted by hundreds of thousands of protestors thronging the streets in what became known as the Sunflower movement in 2014. Cheng is an unambiguous Chinese ethnonationalist,