Back in 2009, the New York Times published an article headlined “Recyclers, Scientists Probe Great Pacific Garbage Patch,” which noted that a group of scientists had “set sail from San Francisco Bay ... to study the planet’s largest known floating garbage dump, about 1,000 miles north of Hawaii.”

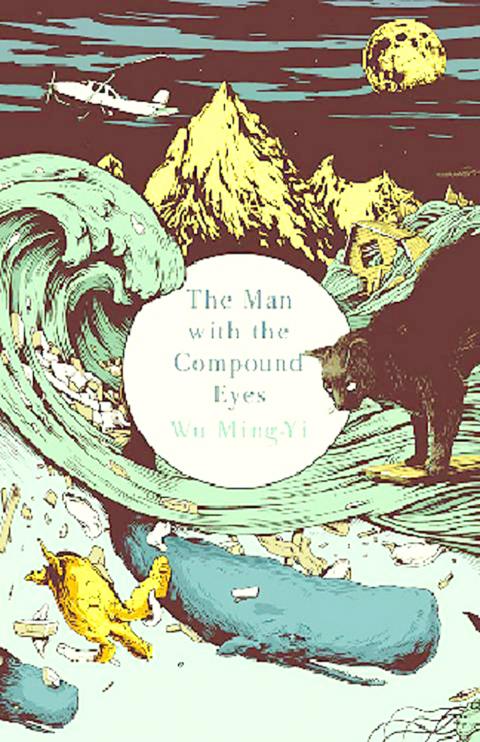

Fast forward to 2013: Taiwanese nature writer Wu Ming-yi (吳明益) has just released an English translation of his The Man with the Compound Eyes (複眼人) that’s aimed at an international readership. The 300-page novel, which has an eye-catching cover for the new British edition, is about that same floating dump.

Wu started writing the novel in 2006 when he read about the floating trash vortex in Chinese-language newspapers. As novelists often do, he concocted a “vision” based on the vortex: An Aboriginal teenager from the imaginary island of Wayo Wayo rides this garbage island and washes up with it one day on the east coast of Taiwan. In the ensuing chaos, the Taiwanese print and TV media have a field day reporting this ecological calamity, and Taiwan — the story is set in the near future of 2020 — is never the same.

In many ways, The Man with the Compound Eyes is a Pacific novel, about a Pacific Islander identity that differs in many ways from the commonplace Han Chinese-centric novels that are published in Taiwan.

The novel stars the boy from Wayo Wayo and a middle-aged Taiwanese college professor named Alice, both of whom are thrown into Taiwan’s east coast wilderness in a search for some lost hikers -- and enlightenment. There’s a cast of characters that expats will know well from their travels along the east coast, and Wu plots the story in very Taiwanese terms. (The English translation by Canadian expat Darryl Sterk, a professor at National Taiwan University, is superb and sensitively captures the nuances of Taiwan’s Aboriginal cultures and languages.)

Wu’s rollercoaster of a story is about wilderness, wildness, wonderment, love. It’s also about “massage parlors” along the east coast where tired and drunk soldiers go for rest and relaxation, with mini-lessons thrown in about various aspects of Aboriginal culture and food.

For readers in Taiwan who have been here for a number of years and know the east coast well, Wu’s novel is sure to strike a chord. But just how this Pacific novel will do overseas with readers in Europe and North America who know little about Taiwan or the Aboriginal cultures here remains to be seen.

As a longtime expat in Taiwan, I read the novel as a critique of modern society’s disregard for our planet’s ecology and environment — a wake-up call, in other words, for Taiwan and the rest of the world.

Readers overseas might find Wu’s story merely a pleasant diversion from the daily grind. You may not have to know much about Taiwan or insect eye biology to enjoy The Man with the Compound Eyes, and the mid-book chapters about that reveal the mystery behind the man with the compound eyes are perhaps the best writing to ever come out of a Taiwan novel. Some readers have drawn comparisons between the novel and Yann Martel’s Life of Pi. Yes, it’s that kind of book, and it would make that kind of movie, too.

Wu’s work began its literary life as a mostly-neglected, unheralded Chinese-language novel in 2011. Taiwan’s Ministry of Culture and the National Museum of Taiwan Literature (國立台灣文學館) used their resources and contacts to help set the book on its way to translation and overseas publication.

Published by Harvill Secker in London last month, the book will be released in New York in 2014, with a French edition as well. The US edition of the book, for reasons that only publishing and marketing industry executives know for sure, will not be released until next year. Readers in Taiwan and elsewhere who want to order the book can use the British Amazon Web site to purchase the UK edition.

Once I started reading this edition, I couldn’t put it down, and over the course of several days I felt that I had ventured into a new, uncharted territory concocted by a Taipei visionary. Part South American magical realism, part Margaret Atwood rollercoaster of the imagination, The Man with the Compound Eyes is a wild story that’s been mashed up into art, and you don’t need compound eyes to appreciate its unique vision.

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name