Robert Hughes, who has died aged 74 after a long illness, dismissed the notion of Crocodile Dundee as a representative Australian figure as “macho commedia dell’arte.” All the same, Hughes as the Crocodile Dundee of art criticism is too good a parallel to reject: burly ocker from the outback, tinny in left hand, confronted by New York aesthete armed with stiletto, reaches with his right hand for his own massive bush knife, commenting slyly to his terrified assailant: “Now that’s what I call a knife.”

I described him in the Guardian once as writing the English of Shakespeare, Milton, Macaulay and Dame Edna Everage; Hughes enjoyed the description. His prose was lithe, muscular and fast as a bunch of fives. He was incapable of writing the jargon of the art world, and consequently was treated by its mandarins with fear and loathing. Much he cared.

When he reached a mass audience for the first time in 1980 with his book and television series The Shock of the New, a history of modern art starting with the Eiffel Tower and graced with a title that still resounds in 100 later punning imitations, some of the BBC hierarchy greeted the proposal that Hughes should do the series with ill-favoured disdain. “Why a journalist?” they asked, remembering the urbanity of Lord Clark of Civilization.

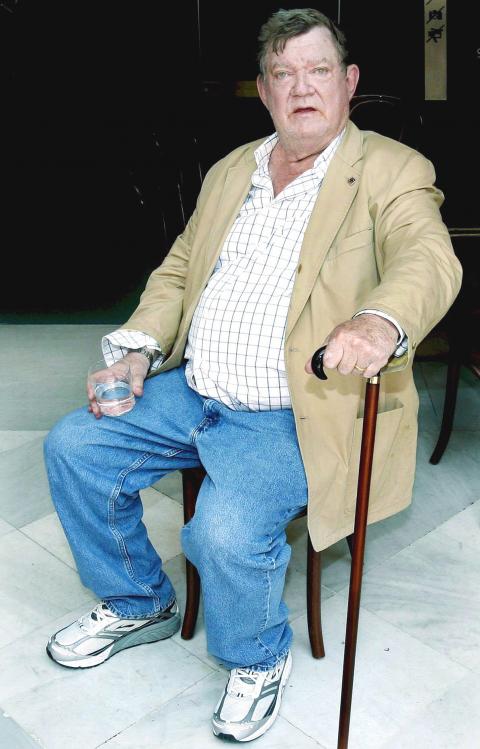

photo: EPA

He gave them their answer with the best series of programs about modern art yet made for television, low on theory, high on the kind of epigrammatic judgment that condenses deep truths. Van Gogh, he said, “was the hinge on which 19th-century romanticism finally swung into 20th-century expressionism.” Jackson Pollock “evoked that peculiarly American landscape experience, Whitman’s ‘vast Something,’ which was part of his natural heritage as a boy in Cody, Wyoming.” And his description of the cubism of Picasso and Braque still stands as the most coherent 10-page summary in the literature.

Hughes was born in Sydney into a family of lawyers descended from an Irish policeman who had emigrated to Australia 100 years before Robert’s birth. This was something of which Hughes was obscurely ashamed, because convicts were to be the heroes of his great work of Australian social history, The Fatal Shore (1987). His father died when he was 12, and he went to a Jesuit boarding school, St Ignatius college.

At Sydney University, where he went to study architecture, he was academically undistinguished. In his words: “I actually succeeded in failing first year arts, which any moderately intelligent amoeba could have passed.”

All the same, he went on at the age of 28 to write a book on The Art of Australia. He himself later dismissed this as juvenilia. In truth, it is a useful source on Australian art. After its publication the popular historian Alan Moorehead advised Hughes, who by now was making a bare living as a freelance architectural writer, to go to Europe.

Hughes took the advice, traveled around the great art capitals and the dodgier casinos, washed ashore in London, wrote art criticism for the London-based Sunday Times which, with the proviso that art did not have the hold on the public imagination then that it does now, had something of the same effect as the young Kenneth Tynan erupting in the theatre columns of the Observer. In London he wrote a book called Heaven and Hell in Western Art (1969) that bombed. However, a Time magazine executive happened upon a copy, leafed through it, and promptly hired Hughes as art critic. In 1970 he moved to Manhattan and wrote for Time for the rest of the century.

The Shock of the New was a success around the world; the book was revised and republished in 1991. But, when Moorehead took Hughes under his wing and gave him shelter for a couple of months at his house in Porto Ercole, Tuscany, he also advised him that if he wanted to find a big subject for a book, he ought to consider convicts. Convicts! thought Hughes. I didn’t come all this way to think about convicts but about Piero della Francesca.

Nonetheless, the seed was planted. And when, in tackling a TV series on Australian art (called Landscape with Figures), Hughes could find no book to tell him about the experience of Australia’s early settlers, in effect the cultural background, he was committed. “Our past was either denied or romanticized. I wrote The Fatal Shore to explain it to myself.”

His private working title for the book was Kangaroots. In the public records office he found a privy council envelope marked Convict Ms, tied with faded ribbon still bright red in the knots and containing rat-nibbled papers bearing firsthand testimony of the experience of transportation under George III. The rest is history, 688 pages of it.

He followed this in 1990 with a study of Frank Auerbach, a painter whom he much admired, not least for his refusal to paint by the yard, either bespoke or made to measure. In a more dogged way, the British painter possessed the qualities that are most to be valued in Hughes himself and which are demonstrated in his collection of essays Nothing If Not Critical (1991).

Normally these collections of journalists’ cuttings are not much of an advance on vanity publishing. Hughes’s collection is a jewel box. Here he is on Watteau’s “musicality:” “it lives in pauses, silences between events. He was a connoisseur of the unplucked string, the immobility before the dance, the moment that falls between departure and nostalgia.” And on a new manifestation of fashionable Manhattan, Hughes sets out his stall in the first sentence: “A taste for Alex Katz’s work is easily acquired, but is it obligatory?”

Such certitude; but Hughes could also leave the door quietly ajar: “One may wonder if any painter in the last century put more meaning into his sense of color than Gauguin; and while one is under the spell of this show, it seems quite certain that none except Van Gogh and Cezanne did.”

His blithe clearsightedness always eschewed ideology, so that when he essayed into the broader cultural scene with his book excoriating American political correctness, Culture of Complaint: The Fraying of America (1993), he found himself ducking flak from left and right. And in 1995 a Time cover story on the assault on federal funding of the arts caused such outrage that Newt Gingrich, the house speaker, demanded and got a right of reply.

In 1999 Hughes had a near-fatal car crash in Western Australia, from which legal complications followed. The episode provided the starting point for his memoir Things I Didn’t Know (2006).

The hallucinations he suffered after the accident led him to identify even more strongly with an artist taken up with grotesques and horrors, and in 2004 he produced a long-planned book, Goya. That was also the year of his BBC television sequel program, The New Shock of the New, which regretted the growing power of money and celebrity in art. These themes recurred in a TV program criticizing Damien Hirst in 2008, and there was also plenty of scope for sharp observation in his last book, the historical survey Rome (2011).

Hughes is survived by his third wife, Doris Downes. His previous marriages ended in divorce, and in 2002 his son by his first wife took his own life.