Battles for acceptance by gay and lesbian students have erupted in the places that expect it the least: the scores of Bible colleges and evangelical Christian universities that, in their founding beliefs, see homosexuality as a sin.

Decades after the gay rights movement swept the country’s secular schools, more gays and lesbians at Christian colleges are starting to come out of the closet, demanding a right to proclaim their identities and form campus clubs, and rejecting suggestions to seek help in suppressing homosexual desires.

Many of the newly assertive students grew up as Christians and developed a sense of their sexual identities only after starting college, and after years of inner torment. They spring from a new generation of evangelical youths that, overall, holds far less harsh views of homosexuality than its elders.

Photo: Bloomberg

But in their efforts to assert themselves, whether in campus clubs or more publicly on Facebook, gay students are running up against administrators who defend what they describe as God’s law on sexual morality, and who must also answer to conservative trustees and alumni.

Facing vague prohibitions against “homosexual behavior,” many students worry about what steps — holding hands with a partner, say, or posting a photograph on a gay Web site — could jeopardize scholarships or risk expulsion.

“It’s like an unstoppable force meeting an immovable object,” said Adam Short, a freshman engineering student at Baylor University who is openly gay and has fought, without success, for campus recognition of a club to discuss sexuality and fight homophobia.

A few more liberal religious colleges, like Belmont University in Nashville, which has Baptist origins, have reluctantly allowed the formation of gay student groups, in Belmont’s case after years of heated debate, and soon after the university had forced a lesbian soccer coach to resign.

But the more typical response has come from Baylor, which with 15,000 students is the country’s largest Baptist university, and which has refused to approve the sexuality forum.

“Baylor expects students not to participate in advocacy groups promoting an understanding of sexuality that is contrary to biblical teaching,” said Lori Fogleman, a university spokeswoman.

Despite the rebuff, more than 50 students continue to hold weekly gatherings of their Sexual Identity Forum, and will keep seeking the moral validation that would come with formal status, said Samantha Jones, a senior and president of the group.

“The student body at large is ready for this,” said Saralyn Salisbury, Jones’ girlfriend and also a senior at Baylor. “But not the administration and the regents.”

At Abilene Christian University in Texas, several students are openly gay, and many more are pushing for change behind the scenes. Last spring, the university refused to allow formation of a Gay-Straight Alliance.

“We want to engage these complex issues, and to give help and guidance to students who are struggling with same-sex attraction,” said Jean-Noel Thompson, the university’s vice president for student life. “But we are not going to embrace any advocacy for gay identity.”

At Harding University in Arkansas, which like Abilene Christian is affiliated with the Churches of Christ, half a dozen current and former students posted an online magazine in early March featuring personal accounts of the travails of gay students. The university blocked access to the site on the university’s Internet server, which helped cause the site to go viral in the world of religious universities.

At chapel, Harding’s president, David Burks, told students that “we are not trying to control your thinking,” but that “it was important for us to block the Web site because of what it says about Harding, who we are, and what we believe.” Burks called the site’s very name, huqueerpress.com, offensive.

Most evangelical colleges say they do not discipline students who admit to same-sex attractions — only those who engage in homosexual “behavior” or “activity.” (On evangelical campuses, sexual intercourse outside marriage is forbidden for everyone.)

Abilene Christian sees a big difference, Thompson said, between a student who is struggling privately with same-sex feelings, and “a student who in e-mails, on Facebook and elsewhere says ‘I am publicly gay, this is a lifestyle that I advocate regardless of where the university stands.’”

Amanda Lee Genaro said she was ejected in 2009 from North Central University, a Pentecostal Bible college in Minneapolis, as she became more assertive about her gay identity. She had struggled with her feelings for years, Genaro said, when she was inspired by a 2006 visit to the campus of SoulForce, a national group of gay religious-college alumni that tries to spark campus discussion.

“I thought, wow, maybe God loves me even if I like women,” Genaro recalled. In 2009, after she quit “reparative therapy,” came out on MySpace and admitted to having a romantic, if unconsummated, relationship with a woman, the university suspended her, saying she could reapply in a year if she had rejected homosexuality. She transferred to a non-Christian school.

Gay students say they are often asked why they are attending Christian colleges at all. But the question, students say, is unfair. Many were raised in intensely Christian homes with an expectation of attending a religious college and long fought their homosexuality. They arrive at school, as one of the Harding Web authors put it, “hoping that college would turn us straight, and then once we realized that this wasn’t happening, there was nothing you could do about it.”

The students who do come out on campus say that it is a relief, but that life remains hard.

“I’m lonely,” said Taylor Schmitt, in his second year at Abilene Christian after arriving with a full scholarship and a hope that his inner self might somehow change. By the end of his first year, Schmitt said, he accepted his homosexuality. He switched to English from the Bible studies department, which, he said, “reeked of the past deceptions and falsehoods I’d created around myself.”

Rather than transferring and giving up his scholarship, he is taking extra classes to graduate a year early.

Some of the gay students end up disillusioned with Christianity, even becoming atheists, while others have searched for more liberal churches.

David Coleman was suspended by North Central University in his senior year in 2005, after he distributed flyers advertising a gay-support site and admitted to intimate relations (but not sexual intercourse) with other men. He calls the university’s environment “spiritually violent.”

Coleman, 28, is now enrolled at United Theological Seminary of the Twin Cities in New Brighton, Minnesota, which is run by the more accepting United Church of Christ. He still dreams of becoming a pastor.

“I have a calling,” he said.

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,

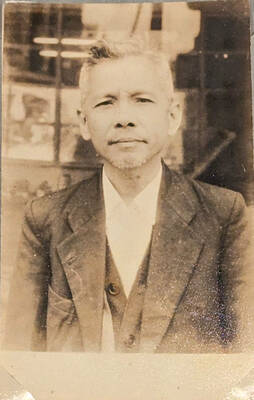

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name

There is no question that Tyrannosaurus rex got big. In fact, this fearsome dinosaur may have been Earth’s most massive land predator of all time. But the question of how quickly T. rex achieved its maximum size has been a matter of debate. A new study examining bone tissue microstructure in the leg bones of 17 fossil specimens concludes that Tyrannosaurus took about 40 years to reach its maximum size of roughly 8 tons, some 15 years more than previously estimated. As part of the study, the researchers identified previously unknown growth marks in these bones that could be seen only