After largely ignoring photography over the past decades, Taiwan’s galleries, museums and art fairs are duly making up for lost time.

The Museum of Contemporary Art, Taipei (MOCA, Taipei) steps into the picture with New Generation Photographers of Taiwan (台灣新世代攝影), a group show that presents the work of 13 “up-and-coming talents.” According to the exhibition introduction, the show attempts to reveal the “perspective of the new era, which goes beyond the traditional and conservative notion of photography held by past generations.”

Who are the old fuddy-duddy photographers that the museum’s blurb refers to? Perhaps Chang Tsai (張才), honored with a retrospective at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum last year? Or, closer to our “era,” Magnum photographer Chang Chien-chi (張乾琦)? It doesn’t say. In any event, this is MOCA’s first group show devoted purely to Taiwanese photographers (last year’s four-person exhibit at the Zhongshan MRT excluded), and it’s perhaps telling that it is shown in its Studio gallery rather than in the museum’s main exhibit space.

Photo courtesy of MOCA, Taipei

Still, curator Suan Hooi-wah (全會華), who runs the Taiwan International Visual Art Center, a gallery devoted to photography, has put together a fine exhibit — though the variety of work on display makes a coherent theme practically impossible. The show does, however, offer a panoramic perspective of what preoccupies this “new generation” of photographers: landscapes, people and art. Sound familiar? It should. And many of the photographers give explicit reference to what has come before.

Every section comes with an artist statement, succinct in style, as a guide for the viewer. Take Sim Chang (張哲榕): He uses “the power of pink to turn this world into an amusement park full of happiness and joy.” He’s not kidding. These cutesy photographs, many shot at theme parks, depict a doll-like woman dressed in a garish pink skirt and yellow rubber boots. Think waipai (outside photography, 外拍), popularized during the Japanese colonial era and revised over the past five years as amateur photographers and would-be models hit Taiwan’s most scenic locations.

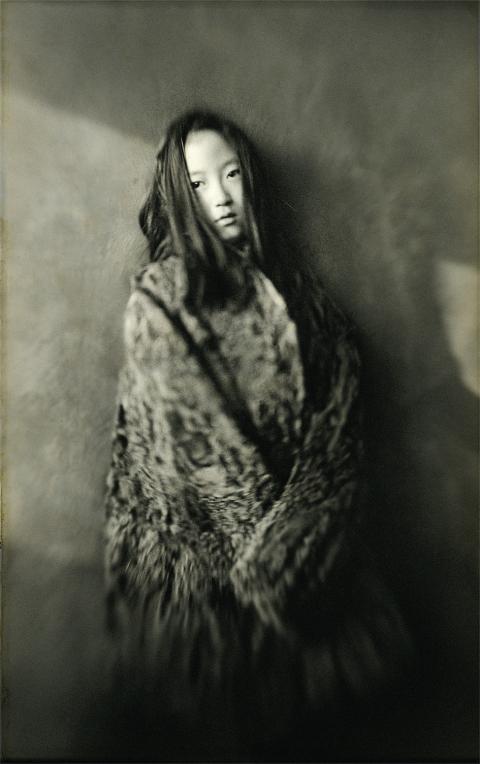

Though Feng Chun-lan (馮君藍) whimsically dubs himself a “foolish sinner,” his monochrome portraits — a man holding an oil lamp or a pouting boy staring melancholically at the viewer — are anything but whimsical. Feng, a pastor at the Taiwan Chinese Rhenish Church (台灣中華基督教禮賢會), employs the precepts of Christian anthropology to create “spiritual portraits” that are, in this reviewer’s opinion, the show’s best because of their haunting psychological depictions of their subjects.

Photo courtesy of MOCA, Taipei

There are also some works evoking particular art styles, such as Deng Bo-ren’s (鄧博仁) delightfully amateurish collage works that comment on fashion and consumerism, and Chou Chih-lung’s (周志龍) surreal bedroom scenes. Elaine Lee’s (李宣儀) multiple-exposure color photographs, without digital manipulation, were inspired by the “atmospheric impressions” of 19th century paintings. For this reviewer, however, they are expressionist renderings at best, reminiscent of Zao Wou-ki’s (趙無極) late-1960s autumnal paintings.

But for the most part, Taiwan’s changing landscapes and cityscapes serve as the exhibit’s focal point. At first glance, Chung Shun-lung’s (鍾順龍) pictures of concrete columns (the kind used to construct freeways) look like drab photos taken by an engineer. Twenty minutes later, however, our party of three was still discussing the images’ techniques and topography.

Chung’s photos delineate the disjunction between past and present, the pillars disappearing into the horizon of some partially constructed future. The photos hint at the ongoing process of industrialization, its pristine white pillars rising up from the rice fields of Taiwan’s rapidly disappearing agricultural society.

Photo courtesy of MOCA, Taipei

Taiwan’s ongoing development is similarly addressed by Chang Hsiao-chen (張小成). His images capture the manner in which a torn down structure imprints itself on the facade of other buildings that remain standing: the muddy silhouette of a small shack or the exposed brick outline of a demolished building. For Chang Hsiao-chen, the walls of a standing building serve as a metaphor for a headstone, the imprint its epitaph.

There is much else to see here that is worthwhile and this reviewer looks forward to future photography exhibits by Taiwan’s artists at MOCA. And, dare I say, in its main gallery space. There are plenty of subjects to draw on: portraiture from World War II to the present, or buildings ranging from pre-Japanese colonial era hovels to the phallic Taipei 101. As this exhibit reveals — along with shows at many other venues over the past two years — Taiwan certainly isn’t lacking in photographers who can depict the present with an eye on the past.

Photo courtesy of MOCA, Taipei

Photo courtesy of MOCA, Taipei

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand