I met Jonathan Fenby in the 1990s when he was editor of the South China Morning Post in Hong Kong (before that he had edited the Observer in London), and it would be hard to imagine a more urbane, genial and even-tempered man. Since then he’s written an adoring but also highly perceptive book on France, and many books about Chinese affairs, most notably a widely praised biography of Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) — Generalissimo: Chiang Kai-shek and the China He Llost (2003). Now he’s been entrusted by Penguin to write a history of modern China that’s certain to be widely consulted, and even read, by students and the general public alike.

It’s next to impossible for history to be written independently of a specific viewpoint. Just to consider two English examples, Gibbon wrote from the viewpoint of an Enlightenment skeptic who saw Rome’s imperial equanimity as undermined by Christian obscurantism, and hoped the

same wouldn’t happen to 18th-century Europe, while Macaulay saw 19th-century England as the product of an evolution from Tory self-interest to Whig sanity and the rule of parliament. An “impartial” record of events, arguably, simply can’t be written. So, what are the fundamental beliefs that underpin Fenby’s capacious and magisterial history of China over the last 158 years?

peace at a price

Essentially, there are two. The first is that China has always, from the First Emperor in 221 BC to today, been ruled by an exceptionally efficient, though sometimes very cruel, bureaucracy that imposed peace at the price of individual self-realization. This was backed by the threat of force, but in general a society that endured longer than any other on earth, and traditionally saw itself as beyond compare, flourished and prospered. But government of the people by the people was never up for discussion.

Secondly, while the Chinese have every reason to be proud of their heritage, they must at the same time come to terms with their history, in particular their recent history. Censuring the Japanese over the Nanjing Massacre, the author writes that his book “argues for a more honest Chinese grasp of its history,” and that in the case of Nanjing the same is true for Japan as well.

The seamless continuity of Chinese governance from Emperor to CCP Chairman and President isn’t a new insight, of course. But the call for a more honest account of the recent past does lead to some strong emphases. The event Fenby is at most pains to highlight is the Beijing Spring of 1989. Including the run-up and the aftermath, this is given four entire chapters (out of a total of 32). By comparison the famine of the early 1950s gets a mere four pages.

The feeling you get is that, though this book will undoubtedly not be distributed in a Chinese translation inside China at present, it is bound, given Penguin’s formidable marketing powers, to be read there, if only in copies imported in travelers’ backpacks. This doesn’t make it earth-shattering, but it will certainly give support to a process already well underway via the Internet.

Fenby has been accused of ignoring sources written in Chinese, and it’s true there isn’t a Chinese character anywhere in the text. But his reading is capacious nonetheless. He has special praise for Roderick MacFarquhar and Michael Schoenhal’s Mao’s Last Revolution (2006) on the Cultural Revolution, and refers frequently to the famous memoirs of Mao’s doctor, The Private Life of Chairman Mao by Li Zhisui (李志綏) (1994). He is appropriately skeptical, though, when it comes to Jung Chang (張戎) and Jon Halliday’s controversial Mao, the Unknown Story of 2005 [reviewed in Taipei Times Jan. 8, 2006].

Here he has an especially interesting observation. Chang and Halliday, he writes, suggested that the Nationalist general Hu Zongnan (胡宗南) was a Communist “sleeper” who deliberately engineered disasters for his own forces. “They give no details of the evidence for this,” Fenby notes, “and Hu’s son threatened legal action in Taiwan. As with other disputed elements in their book, the authors did not reply to inquiries sent through their British publisher on this point.”

out with the truth

Regular readers of Taipei Times will remember that our review was also doubtful about the credibility of this unrelenting reverse-hagiography of the Great Helmsman, best-seller though it proved.

Fenby’s style is everywhere clear and effective, combining apparently well-informed judgment with telling detail. His tone is judicious and honest, and he never engages in rant or vituperative personal asides. But when the great moments arrive he doesn’t hold his punches, and on the darker side of Communism’s past he certainly doesn’t mince his words.

Taiwan’s separate history is touched on here and there, but Fenby is clearly in no two minds about the nation’s separateness. Even Hong Kong, he feels, when it was handed over to China in 1997, was submitting to what was “in many ways another outside ruler.”

As Fenby wrote in a review published in Taipei Times on March 12, 2006, “Can a nation that depends for its growth and stability on engaging with the rest of the world continue to deny the truths of its past?” By this date he must have been well advanced on this new, comprehensive overview, and the same insistence on honesty about former errors is at its heart.

China has much to be proud of, Fenby acknowledges, both in its ancient civilization and in its achievements over the past 30 years. But for its government to tell the truth and admit to old mistakes can only help it attain genuine dignity and respect, not to mention finally winning the unconditional support of its own people.

The Taipei Times last week reported that the rising share of seniors in the population is reshaping the nation’s housing markets. According to data from the Ministry of the Interior, about 850,000 residences were occupied by elderly people in the first quarter, including 655,000 that housed only one resident. H&B Realty chief researcher Jessica Hsu (徐佳馨), quoted in the article, said that there is rising demand for elderly-friendly housing, including units with elevators, barrier-free layouts and proximity to healthcare services. Hsu and others cited in the article highlighted the changing family residential dynamics, as children no longer live with parents,

It is jarring how differently Taiwan’s politics is portrayed in the international press compared to the local Chinese-language press. Viewed from abroad, Taiwan is seen as a geopolitical hotspot, or “The Most Dangerous Place on Earth,” as the Economist once blazoned across their cover. Meanwhile, tasked with facing down those existential threats, Taiwan’s leaders are dying their hair pink. These include former president Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文), Vice President Hsiao Bi-khim (蕭美琴) and Kaohsiung Mayor Chen Chi-mai (陳其邁), among others. They are demonstrating what big fans they are of South Korean K-pop sensations Blackpink ahead of their concerts this weekend in Kaohsiung.

Taiwan is one of the world’s greatest per-capita consumers of seafood. Whereas the average human is thought to eat around 20kg of seafood per year, each Taiwanese gets through 27kg to 35kg of ocean delicacies annually, depending on which source you find most credible. Given the ubiquity of dishes like oyster omelet (蚵仔煎) and milkfish soup (虱目魚湯), the higher estimate may well be correct. By global standards, let alone local consumption patterns, I’m not much of a seafood fan. It’s not just a matter of taste, although that’s part of it. What I’ve read about the environmental impact of the

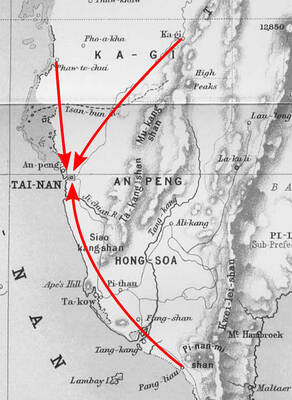

Oct 20 to Oct 26 After a day of fighting, the Japanese Army’s Second Division was resting when a curious delegation of two Scotsmen and 19 Taiwanese approached their camp. It was Oct. 20, 1895, and the troops had reached Taiye Village (太爺庄) in today’s Hunei District (湖內), Kaohsiung, just 10km away from their final target of Tainan. Led by Presbyterian missionaries Thomas Barclay and Duncan Ferguson, the group informed the Japanese that resistance leader Liu Yung-fu (劉永福) had fled to China the previous night, leaving his Black Flag Army fighters behind and the city in chaos. On behalf of the