Soul of a Demon (蝴蝶), celebrated director Chang Tso-chi's (張作驥) first film in five years, almost didn't make it to the big screen. Originally envisioned as a work of magic realism aided by CGI effects, the production came to a halt when the animation production company backed out of the project. After scraping together a new budget, Chang and his team re-shot the movie one year later. The result is a sober human drama about a tormented gangster who is unable to disengage from the cycle of violence and his troubled relationship with his father.

Set in Nanfangao (南方澳), a fishing port built by the Japanese, the film begins when Che (Tseng Yi-che) returns home from jail. Che took the rap for his younger brother, Ren (Cheng Yu-ren), who had stabbed to death the son of a local mob boss.

To reconnect with his semi-Aboriginal roots, Che visits his mother’s grave in Orchid Island (蘭嶼) with his ex-girlfriend Pei (Chen Pei-chun), who is mute from past emotional trauma.

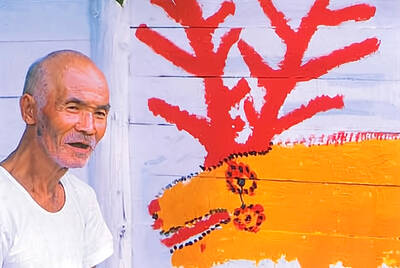

PHOTO: COURTESY OF CHANG TSO CHI FILM STUDIO

Meanwhile, Ren returns from hiding in Japan with the brothers’ father, Chang (Michio Hayashida), whose departure from the family home led to his wife’s suicide. Old hatreds erupt, and violence rears its ugly head.

The title of the film comes from the Tao (達悟) word for butterfly. Tao tribal tradition holds that at the moment of death, a person’s soul leaves their body much in the same way as butterflies flutter towards the sky.

From images of butterfly wings shimmering on bamboo trees and the deserted amusement park where Che is abandoned by his father, to a glove puppet performance on the seashore, the film creates an atmospheric world in which the troubled protagonist is eventually consumed by his past and memories.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF CHANG TSO CHI FILM STUDIO

Though death, wickedness and human tragedy are motives in Chang’s work, the director’s sense of fatalism is taken to new heights in Soul of a Demon: men find no way to escape the vicious cycle of und erworld vendetta and women are either crippled, mute or dead. Chang’s Nanfangao is dismal and bleak, and suffocates the characters.

The fishing port is an ideal vehicle for Chang’s contemplative reflection on Taiwan’s history and the country’s hybrid cultural and political identities. By adding the role of Che’s grandfather, a photographer who came to Nanfangao with a Japanese construction team, to the story, Chang reveals the history of Nanfangao as one of the places where the first wave of Japanese soldiers and civil servants arrived in Taiwan. Che’s conflicts with his family, therefore, can be read as a metaphorical reference to Taiwan’s historical relationships with Japan and the nation’s Aborigines.

With the divine dancing Eight Generals (八家將) practitioners in Ah Chung (忠仔, 1996), the blind and gangsters in Darkness and Light (黑暗之光, 1999) and the deprived youth in The Best of Times (美麗時光, 2002), Chang excels in revealing the beauty and ugliness of life through the stories of social underdogs. In Soul of a Demon, the motifs are all there: gangsters, people with disabilities and a dysfunctional family. Yet the film is likely to be seen as one of Chang’s less successful pieces, since the story is oftentimes strays and becomes lost in the director’s auteurist exercise.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF CHANG TSO CHI FILM STUDIO

The film is, perhaps, like the director himself readily admits, a faithful reflection on the chaos of his life, frustrations and the passing of his father five years ago.

It’s always a pleasure to see something one has long advocated slowly become reality. The late August visit of a delegation to the Philippines led by Deputy Minister of Agriculture Huang Chao-ching (黃昭欽), Chair of Chinese International Economic Cooperation Association Joseph Lyu (呂桔誠) and US-Taiwan Business Council vice president, Lotta Danielsson, was yet another example of how the two nations are drawing closer together. The security threat from the People’s Republic of China (PRC), along with their complementary economies, is finally fostering growth in ties. Interestingly, officials from both sides often refer to a shared Austronesian heritage when arguing for

The ultimate goal of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is the total and overwhelming domination of everything within the sphere of what it considers China and deems as theirs. All decision-making by the CCP must be understood through that lens. Any decision made is to entrench — or ideally expand that power. They are fiercely hostile to anything that weakens or compromises their control of “China.” By design, they will stop at nothing to ensure that there is no distinction between the CCP and the Chinese nation, people, culture, civilization, religion, economy, property, military or government — they are all subsidiary

Nov.10 to Nov.16 As he moved a large stone that had fallen from a truck near his field, 65-year-old Lin Yuan (林淵) felt a sudden urge. He fetched his tools and began to carve. The recently retired farmer had been feeling restless after a lifetime of hard labor in Yuchi Township (魚池), Nantou County. His first piece, Stone Fairy Maiden (石仙姑), completed in 1977, was reportedly a representation of his late wife. This version of how Lin began his late-life art career is recorded in Nantou County historian Teng Hsiang-yang’s (鄧相揚) 2009 biography of him. His expressive work eventually caught the attention

Late last month the Executive Yuan approved a proposal from the Ministry of Labor to allow the hospitality industry to recruit mid-level migrant workers. The industry, surveys said, was short 6,600 laborers. In reality, it is already heavily using illegal foreign workers — foreign wives of foreign residents who cannot work, runaways and illegally moonlighting factory workers. The proposal thus merely legalizes what already exists. The government could generate a similar legal labor supply simply by legalizing moonlighting and permitting spouses of legal residents to work legally on their current visa. But after 30 years of advocating for that reform,