I have long been of the opinion that the entire history of American popular culture - maybe even of Western civilization - amounts to little more than a long prelude to The Simpsons. I don't think I'm alone in this belief. But it does not follow that The Simpsons movie represents a creative peak toward which the show's 18 seasons and 400 episodes have been a long, slow climb. Let's keep things in perspective. The Simpsons is an inexhaustible repository of humor, invention and insight, an achievement without precedent or peer in the history of broadcast television, perhaps the purest distillation of our glories and failings as a nation ever conceived. The Simpsons Movie is, well, a movie.

Don't get me wrong. It's a very funny movie, loaded with dumb jokes that are often as funny as the clever ones, and full of the anarchic, generous, good-natured humor that is the show's enduring signature. From the very start, when Ralph Wiggum stands inside the 20th Century Fox logo and sings along with the company fanfare, to the last frames of the closing credits, The Simpsons Movie provides plenty of amusement for both casual fans and hard-core zealots. It is not better than the best episodes - it's no 22 Short Films About Springfield or Homer's Enemy or Krusty Gets Busted or Lisa the Vegetarian - and it doesn't strain to be. (I'd put it at about the level of Trash of the Titans, the 200th episode, with which it shares an environmental theme.)

Instead of trying to top The Simpsons or sum it all up, the film's director, David Silverman (whose association with the series goes back to the days of The Tracey Ullman Show) and the writers (who among them have at least a century's worth of experience on the show) take advantage of the opportunity to go wider and longer. CinemaScope, the wide-screen format developed by Fox in the 1950s to combat the rise of television, turns out to be the ideal way to appreciate the small-screen, small-town paradise that is Springfield. In a variation on the show's opening sequence, we swoop through the town, seeing it from new angles and appreciating its history and beauty anew.

PHOTOS: COURTESY OF FOX

There are also crowd scenes on a scale rarely attempted on television, spectacles that compensate somewhat for the skimpy screen time granted some of the secondary characters. Everyone has a little, thank goodness, but for my taste there was too much Flanders and not enough Krusty. Less Cletus, please, and more Groundskeeper Willie. And where were Patty and Selma? I will say that the Itchy and Scratchy movie at the beginning is pure genius, though.

At this point, the temptation is strong to rifle through my notes and repeat my favorite jokes - to tell you about Bart's full frontal nudity and Homer and Marge's bedroom scene and the bomb-defusing robot and the many acts of auto-homage that made my inner Comic Book Guy exclaim, "Oh yeah, I remember that episode." Instead, I'll just spoil the plot: Homer does something really stupid. Also, Lisa develops a crush, Bart gets in trouble and Marge expresses concern and disapproval. Sorry.

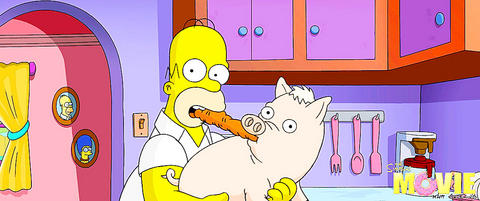

Homer's main screw-up is not necessarily more or less idiotic than anything he's done before. (All I'll say is that it involves a pig.) The consequences, though, are proportionate to what you might expect from a summer blockbuster action movie. That is, they involve Arnold Schwarzenegger, who has been elected president of the US; the elite attack forces of the Environmental Protection Agency; and the near-destruction of Springfield. Also motorcycles.

The head of the EPA is voiced by the Simpsons stalwart Albert Brooks, but the movie is generally light on celebrity cameos and voice-overs, properly emphasizing the talents of the series regulars (Dan Castellaneta, Julie Kavner, Yeardley Smith and Nancy Cartwright as the family, with Hank Azaria and Harry Shearer filling out much of the non-Simpson Springfield phone directory). There is Green Day, performing an excellent revved-up version of Danny Elfman's theme song, but other than that the filmmakers stick to the solid core of family and town, and to the mixture of irreverence and sentiment that has underwritten the program's longevity.

One of the esoteric pursuits that divert Simpsons devotees is what might be called the question of authorship. A movie may be the work of a single, imperial auteur, but a television comedy, more often than not, arises from the collective, at times antagonistic labor of a bunch of writers in a room. It is easy enough to identify the graphic style and populist sensibilities of Matt Groening, and to intuit the sharp, fuzzy humanism of James Brooks. But over the years dozens of writers have passed through the bungalows on the Fox lot where The Simpsons is written. Many have stuck around, come back after grazing elsewhere or left traces of their influence behind. They are, as a group, responsible for the show's variety and its consistency, for its high points and its occasional doldrums.

Quite a few storied figures of Simpsons history turn up in the movie credits - the screenplay is attributed to Groening, Brooks, Al Jean, Ian Maxtone-Graham, George Meyer, David Mirkin, Mike Reiss, Mike Scully, Matt Selman, John Swartzwelder and Jon Vitti, several of whom have served in the crucial and mysterious role of show runner - and this is a sign that the movie is more to its makers than a by-product or an afterthought.

Except, of course, that it inevitably is. Ten or 15 years ago, The Simpsons Movie, which has been contemplated for almost as long as the show has been on the air, might have felt riskier and wilder. But The Simpsons, for all its mischief and iconoclasm, has become an institution, and that status has kept this film from taking too many chances. Why mess with the formula when you can extend the brand? Do I sound disappointed? I'm not, really. Or only a little. The Simpsons Movie, in the end, is as good as an average episode of The Simpsons. In other words, I'd be willing to watch it only - excuse me while I crunch some numbers here - 20 or 30 more times.

April 28 to May 4 During the Japanese colonial era, a city’s “first” high school typically served Japanese students, while Taiwanese attended the “second” high school. Only in Taichung was this reversed. That’s because when Taichung First High School opened its doors on May 1, 1915 to serve Taiwanese students who were previously barred from secondary education, it was the only high school in town. Former principal Hideo Azukisawa threatened to quit when the government in 1922 attempted to transfer the “first” designation to a new local high school for Japanese students, leading to this unusual situation. Prior to the Taichung First

When the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese forces 50 years ago this week, it prompted a mass exodus of some 2 million people — hundreds of thousands fleeing perilously on small boats across open water to escape the communist regime. Many ultimately settled in Southern California’s Orange County in an area now known as “Little Saigon,” not far from Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton, where the first refugees were airlifted upon reaching the US. The diaspora now also has significant populations in Virginia, Texas and Washington state, as well as in countries including France and Australia.

On April 17, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) launched a bold campaign to revive and revitalize the KMT base by calling for an impromptu rally at the Taipei prosecutor’s offices to protest recent arrests of KMT recall campaigners over allegations of forgery and fraud involving signatures of dead voters. The protest had no time to apply for permits and was illegal, but that played into the sense of opposition grievance at alleged weaponization of the judiciary by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) to “annihilate” the opposition parties. Blamed for faltering recall campaigns and faced with a KMT chair

Article 2 of the Additional Articles of the Constitution of the Republic of China (中華民國憲法增修條文) stipulates that upon a vote of no confidence in the premier, the president can dissolve the legislature within 10 days. If the legislature is dissolved, a new legislative election must be held within 60 days, and the legislators’ terms will then be reckoned from that election. Two weeks ago Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (蔣萬安) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) proposed that the legislature hold a vote of no confidence in the premier and dare the president to dissolve the legislature. The legislature is currently controlled