Salvador Dali was the last of the great cultural outlaws, and probably the last genius to visit our cheap and gaudy planet. Look around you with an unbiased eye and, alas, you will see no painter of genius, and no novelist, poet, philosopher or composer who takes his or her place in that top tier without asking our permission. I think Dali was the greatest painter of the 20th century — far more important than Picasso, who was a 19th-century painter most at home in his studio, with the familiar props of guitars, jugs of wine and stoical girlfriends who must have wondered what was going on in his self-enclosed mind. Picasso was driven around Cannes in his American car, but he seems to have seen nothing of the world on the far side of the windscreen.

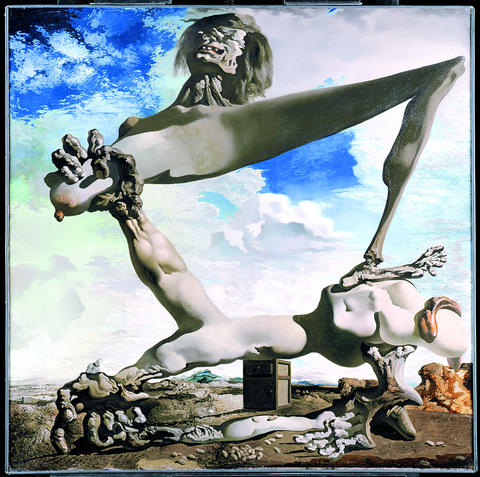

With Dali, we have the immediate sense that he not only saw the increasingly sinister world of the 1930s in all its lurid truth, but fully grasped the deranged unconscious forces that propelled Hitler and Stalin into the daylight. His paintings are like stills from an elegant newsreel filmed inside our heads, and we could reconstitute the whole of the last century from them, all its voyeurism, barbarism, scientific genius and self-disgust.

Dali's masterpiece and, I believe, the greatest painting of the 20th century is The Persistence of Memory, a tiny painting not much larger than the postcard version, containing the age of Freud, Kafka and Einstein in its image of soft watches, an embryo and a beach of fused sand. The ghost of Freud presides over the uterine fantasies that set the stage for the adult traumas to come, while insects incarnate the self-loathing of Kafka's Metamorphosis and its hero turned into a beetle.

PHOTO: AFP

The soft watches belong to a realm where clock time is no longer valid and relativity rules in Einstein's self-warping continuum.

What monster would grow from this sleeping embryo? It may be the long eyelashes, but there is something feminine and almost coquettish about this little figure, and I see the painting as the 20th century's Mona Lisa, a psychoanalytic take on the mysterious Gioconda smile. If the Mona Lisa, as someone said, looks as if she has just dined on her husband, then Dali's embryo looks as if she dreams of feasting on her mother.

How do we explain the huge popularity of this painting, and all of Dali's work? Suddenly, surrealism is everywhere, in those citadels of respectability such as the Tate, the V&A and the Hayward galleries in London. Put on a surrealism show and the crowds flock, quietly absorbing these strange and irrational images. It's as if people realize that reason and rationality no longer provide an adequate explanation for the world we live in. The lights may still be on, but a new Dark Age is drawing us towards its shadows, and we turn to the surrealists as our best guides to the underworld.

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

The 20th century was a vast textbook of psychopathology, but it took the surrealists a long time to be accepted. In the 50s, when I was hunting for illustrations of the latest Dali or Magritte, I was more likely to find them in the Daily Mirror or Daily Express, held up as objects of ridicule. Surrealism as a whole remained beyond the critical pale until well into the 1960s, and most of its great painters — Max Ernst, Magritte, Paul Delvaux — had to wait until their last years before they were accepted by the bowler- hatted bureaucrats of British art. They died loaded with honors, prizes and, worst of all, respectability.

Dali was the great exception, and never saw a bowler doffed in his direction. He alone remained faithful to the surrealists' first commandment: shock the bourgeoisie. Right to the end he upset the critics and cultural valuers of the arts establishment by posing as their worst nightmare: a genius and show-off greedy for money. He expressed his contempt for them by signing thousands of blank sheets of paper (at US$100 a time, so they say), well aware that a flood of inferior copies would drench the market, in the ultimate surrealist act that would make people unsure whether they owned a real Dali or a fake. And, anyway, did it matter?

A strong factor in Dali's ostracism from the critical fold was always his exhibitionism: the absurd moustachios, the gigolo manner, the preposterous English in which he yoked together rhinoceros horns and concepts from nuclear physics, his department-store window stunts, his playing up to the American news media, his strangely asexual devotion to his wife, Gala ("she has the look that pierces walls"), the bizarre space he occupied somewhere between American Vogue and a seaside freak show. The paintings came and went, as original and voluptuous as ever, but their seriousness was diminished by the stunts and tomfoolery. Only now are people beginning to look earnestly at the entirety of his lifetime's work and judge him as a painter rather than a performer.

What has changed? In part, it is the behavior of the contemporary art world. Exhibitionism, of one kind or another, is now the frame around all present-day artists, from Gilbert & George to Tracey Emin and Damien Hirst, the Chapman Brothers and a host of other YBAs. Dali never put on a little girl's party frock, but his eccentric antics now seem the norm in our celebrity culture.

Most important of all, though, in our revaluation of Dali, is the lens through which we see his paintings. We no longer live in a literary culture, and the human eye has been fine-tuned by a half-century of film and television. Dali's paintings, with their distant horizon lines, pseudo-Renaissance perspectives and mentalized stage-sets, are naturals for the age of the plasma TV screen. Our attention spans have shrunk to a single film-frame, and when we look at a Dali painting we can instantly construct the rest of the movie from the key frame that he offers us.

Film fascinated Dali from his earliest days, and he collaborated with Luis Bunuel to produce two classics of surrealist cinema, Un Chien Andalou (1928) and L'Age d'Or (1930). Both will be shown at the exhibition Dali & Film, which opens at Tate Modern tomorrow. Even today, after a deluge of horror and exploitation movies of the goriest kind, the films seem deeply shocking.

Un Chien Andalou opens with the thuggishly handsome Bunuel standing on a darkened balcony, thoughtfully stropping a cut-throat razor. He steps inside and approaches a young woman waiting for him, as a sliver of cloud slices across the moon. Then, in one of the most famous shots in all cinema, the razor appears to slice across the woman's eye, releasing its vitreous fluid. In fact, a cow's eye was slashed, but Bunuel is reported to have felt sick for days after filming the sequence. How Dali felt isn't known, though he probably thought up the sequence.

After that bracing start, there are a number of scenes involving an anguished young man who seems to be trying to make emotional contact with a turbulent young woman who repels his advances. There are no clues to behavior. Ants pour from a hole in the young man's palm. Rebuffed, he puts on a curious harness and drags towards the young woman a huge contraption consisting of two priests lying on their backs, tied to a grand piano across which is draped a dead donkey.

What comes through this 15-minute film is the feeling that it would all make sense if its scenes were assembled in the right order. But of course it would not make sense, whatever the order, and I take this to be the point of the film. The reality we inhabit daily, our domestic interiors and their emotional dramas, the hands helplessly caressing a young woman's breasts, the tennis racket she uses to drive away her unwanted suitor (the surrealists were intensely middle class), the small section of space-time we blunder through, are all equally unreal, though meaning and sanity seem tantalizingly within our grasp.

L'Age d'Or is a longer and more provocative film, guying the Catholic Church and sending up as many of our cherished notions as its director and scriptwriter can turn their attention to. A blind man is abused, a son is casually shot by his father, an old woman is slapped, the heroine sucks rapturously on the toe of a marble Apollo. Christ is played by the hero of Sade's 120 days of Sodom, and the film ends with a crucifix on which several scalps are nailed. I prefer Un Chien Andalou, but in L'Age d'Or there is the same sense that everyday reality is only a hand's breadth away, but will never be reached. In short, rather like life today. Welcome to the surrealist world, which you never knew you inhabited.

April 28 to May 4 During the Japanese colonial era, a city’s “first” high school typically served Japanese students, while Taiwanese attended the “second” high school. Only in Taichung was this reversed. That’s because when Taichung First High School opened its doors on May 1, 1915 to serve Taiwanese students who were previously barred from secondary education, it was the only high school in town. Former principal Hideo Azukisawa threatened to quit when the government in 1922 attempted to transfer the “first” designation to a new local high school for Japanese students, leading to this unusual situation. Prior to the Taichung First

When the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese forces 50 years ago this week, it prompted a mass exodus of some 2 million people — hundreds of thousands fleeing perilously on small boats across open water to escape the communist regime. Many ultimately settled in Southern California’s Orange County in an area now known as “Little Saigon,” not far from Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton, where the first refugees were airlifted upon reaching the US. The diaspora now also has significant populations in Virginia, Texas and Washington state, as well as in countries including France and Australia.

On April 17, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) launched a bold campaign to revive and revitalize the KMT base by calling for an impromptu rally at the Taipei prosecutor’s offices to protest recent arrests of KMT recall campaigners over allegations of forgery and fraud involving signatures of dead voters. The protest had no time to apply for permits and was illegal, but that played into the sense of opposition grievance at alleged weaponization of the judiciary by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) to “annihilate” the opposition parties. Blamed for faltering recall campaigns and faced with a KMT chair

Article 2 of the Additional Articles of the Constitution of the Republic of China (中華民國憲法增修條文) stipulates that upon a vote of no confidence in the premier, the president can dissolve the legislature within 10 days. If the legislature is dissolved, a new legislative election must be held within 60 days, and the legislators’ terms will then be reckoned from that election. Two weeks ago Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (蔣萬安) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) proposed that the legislature hold a vote of no confidence in the premier and dare the president to dissolve the legislature. The legislature is currently controlled