The bold, flowing, multicolor gowns that add to Colonel Muammar Qaddafi's reputation for flamboyant and quirky behavior may actually make a subtle point.

They are, in fashion terms, what some people would like to see Libya become — a blending of the traditional and the modern. Rabia Ben Barka knows because, she said, she often designs clothes for the colonel, known here as Brother Leader.

Ben Barka, a slight, cautious woman, has waited a lifetime to have the chance to combine the styles she learned in the capitals of Europe with the traditions of Libya, her North African homeland. But Libya was not always open to Ben Barka; it was not open to anyone who sought to pierce its isolation.

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

Or to recover family assets seized by the state.

Ben Barka began life lucky, born into a very rich family. Her father owned eight textile factories in Tripoli. Her uncles owned buildings and hotels.

Then she wasn't lucky. Or rich.

Qaddafi (he was a captain at the time) and a small group of officers staged a coup d'etat in 1969 and ousted the monarchy. Once in power, the colonel (he promoted himself) nationalized almost everything on his way to establishing a socialist-style economy. The government took the eight factories, the hotels and the other buildings.

Ben Barka was abroad at the time, attending an elite boarding school in Switzerland. She moved on from there to Rome, w here she studied with leading fashion designers. In 1976, when she was 26, she said, she won a regional fashion show in Egypt, defeating better known Egyptian and Lebanese designers.

But her career never took off, she said, because she could not work from her home in Tripoli and pursue her passion of combining traditional Libyan dress with modern Western styles. "I missed many years," she said.

Instead she did work for others, designing lines in Rome while trying to slip in her own Libyan-inspired flourishes. But her heart was always in Libya, and her aim was to return.

Ultimately, she said, the ticket back came through the family that took everything away: the Qaddafis.

First, though, a note of caution. Ben Barka may not like what Libya has become under the rule of Brother Leader, but she will not say it. She may not like that her family's assets were stripped and her life's work stalled, but she will not talk about that either.

She has made a mental accommodation with what Libya is under Qaddafi. It is much like the accommodation many intellectuals and artists have made to work, or simply live, in authoritarian states like Iraq under Saddam Hussein or the Soviet Union.

"They call me the ambassadress of Libyan fashion," she said. "I am an artist. I have nothing to do with politics."

She said the door to Tripoli was first cracked open for her by Qaddafi's daughter, Aisha, who apparently liked Ben Barka's designs. It was during the 1980s, and Ben Barka was coming in and out of the country, traveling between her temporary home in Rome and her birthplace, Tripoli. Over time, she built up enough contacts that she was able to open her own firm.

She does not want to alienate her most important client in any way, so the details of her climb to success are thin and come slowly. But she says that eventually, she moved from daughter, to wife, to Brother Leader himself.

"I was the leader's designer," she finally allowed.

Ben Barka's studio is in downtown Tripoli, off a busy traffic circle and not very far from where Qaddafi lives. The road in front of is unpaved, littered and rutted.

But it is a thrill for her, because the studio is in one of her father's old textile factories; through her work and relations with the first family, she said, she was able to convince officialdom to return at least something that once belonged to the family business.

Inside it is cold and dank like a factory, with cement floors, walls and ceilings. There are four or five sewing machines in the work space. There is a large picture of Brother Leader leaning against one wall, and racks of clothing that speak to her goal of fashioning Libyan identity in a modern context.

"We cannot pretend to be European or American," she said, as she flipped through racks of clothing as though gently turning the pages of an old family photo album. Libyan clothing reflects the country's Islamic, African and desert identities, all of which she plays with and builds on.

For both men and women there are bold stripes and intricate embroidered patterns. She sometimes uses materials woven with strands of gold and silver. For women there can also be pants, often beneath a traditional flowing veil that extends to the shoulders, like a shawl.

For men there are Western-style suits, livened up with embroidery on the sleeves, chest and waist. There are plays on traditional color patterns; black and white, for example, where tradition calls for only white.

"I didn't want to lose our character," she said.

Though her work was a shock to some Libyan traditionalists, over the years, she said, she has won a following here, dressing foreign diplomats and their spouses, staging fashion shows for visiting delegations and, of course, continuing her work for the first family. Now, she said, she grapples with another problem: bootleggers copying her designs.

But still, as Libya feels its way between isolation and integration, her audience is limited, her opportunities stunted. The country has begun to move toward economic reform, while preserving Qaddafi's political system. She cannot, for example, manufacture new clothing for every show, because the gold and silver threads are costly. She has been unable to figure out how to show her work in the US.

Few people can actually wear the haute couture of Europe off the runway. High-end outfits are for fashion shows and the Academy Awards. Ben Barka's clothing would also be tough to wear for a day at the office, or even a night out on the town. But Qaddafi is not afraid to wear a powder-blue jumper or lime-green robes.

It is impossible in Libya to get a fix on the colonel's thinking, so what he sees in the designs remains a mystery. But Ben Barka's idea is that his clothing represents a marriage of where Libya was and where she would like to see it go.

Standing in her studio, she held up a shiny suit with narrow black and gold stripes. The cut was Western and the pattern Libyan. A visiting friend pushed her to acknowledge that she had made one just like it for Qaddafi.

But she demurred. That was as far as she would go about her famous client.

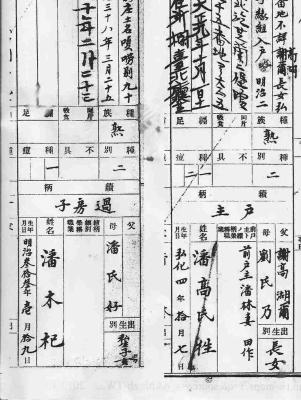

Feb. 9 to Feb.15 Growing up in the 1980s, Pan Wen-li (潘文立) was repeatedly told in elementary school that his family could not have originated in Taipei. At the time, there was a lack of understanding of Pingpu (plains Indigenous) peoples, who had mostly assimilated to Han-Taiwanese society and had no official recognition. Students were required to list their ancestral homes then, and when Pan wrote “Taipei,” his teacher rejected it as impossible. His father, an elder of the Ketagalan-founded Independence Presbyterian Church in Xinbeitou (自立長老會新北投教會), insisted that their family had always lived in the area. But under postwar

In 2012, the US Department of Justice (DOJ) heroically seized residences belonging to the family of former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁), “purchased with the proceeds of alleged bribes,” the DOJ announcement said. “Alleged” was enough. Strangely, the DOJ remains unmoved by the any of the extensive illegality of the two Leninist authoritarian parties that held power in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Taiwan. If only Chen had run a one-party state that imprisoned, tortured and murdered its opponents, his property would have been completely safe from DOJ action. I must also note two things in the interests of completeness.

Taiwan is especially vulnerable to climate change. The surrounding seas are rising at twice the global rate, extreme heat is becoming a serious problem in the country’s cities, and typhoons are growing less frequent (resulting in droughts) but more destructive. Yet young Taiwanese, according to interviewees who often discuss such issues with this demographic, seldom show signs of climate anxiety, despite their teachers being convinced that humanity has a great deal to worry about. Climate anxiety or eco-anxiety isn’t a psychological disorder recognized by diagnostic manuals, but that doesn’t make it any less real to those who have a chronic and

When Bilahari Kausikan defines Singapore as a small country “whose ability to influence events outside its borders is always limited but never completely non-existent,” we wish we could say the same about Taiwan. In a little book called The Myth of the Asian Century, he demolishes a number of preconceived ideas that shackle Taiwan’s self-confidence in its own agency. Kausikan worked for almost 40 years at Singapore’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, reaching the position of permanent secretary: saying that he knows what he is talking about is an understatement. He was in charge of foreign affairs in a pivotal place in