Like a lot of people, after a particularly long day at work, David Niddam likes to have a beer and relax. Unlike most people, he can explain how the alcohol in that beer moves from his bloodstream to his spinal cord, cerebellum and cerebral cortex, where it increases dopamine and norepinephrine levels, decreases the transmission within his acetylcholine systems, bumps up the production of beta-endorphin in his hypothalamus and puts a smile on his face.

Niddam works in the Integrated Brain Research Unit (IBRU) of Taipei Veterans General Hospital, a facility under the administration of both the hospital and National Yangming University. Earlier this week he gave the Taipei Times a tour of the facilities, where current research topics include epilepsy, cognitive linguistics, mood disorders and the genetic mapping of spino-cerebellar ataxia, a type of neuro-muscular degeneration specific to Taiwanese.

For his part, Niddam researches pain. He has been with the IBRU since 2002, coming to Taiwan after completing his doctoral studies at Aalborg University in his native Denmark. He chose to work at the IBRU, he said, because the facility is among the best in the world in terms of the quantity and quality of hardware available to researchers, making his research a little less painful.

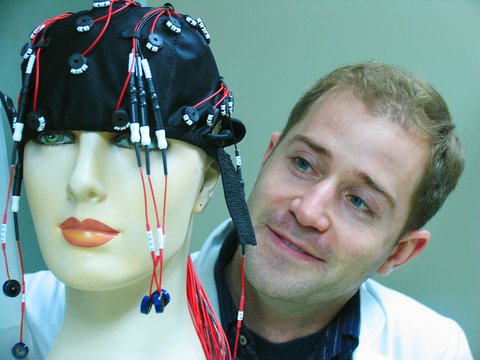

PHOTO: DAVID MOMPHARD, TAIPEI TIMES

"In brain research the gold standard is to know which local brain networks are involved in a specific task and how they are connected through global networks," he said.

Equally important are knowing the order in which those networks are activated, being able to follow the information that flows through them, and understanding the biochemistry involved in the process.

"Ideally, we would like to have all that information from the same subjects or patients," Niddam said, instead of piecing together bits of information from hospitals and research centers across the globe.

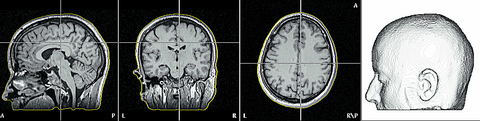

PHOTO COURTESY OF DAVID NIDDAM

To make that possible, National Yangming University and Taipei Veterans Hospital have established the Research Center for Neuroimaging and Neuroinformatics to bring into one facility all the instruments required in neurological research.

"This is a new trend worldwide and it's called multimodal brain imaging," Niddam said, adding that the researchers at National Yangming University and the Veterans Hospital were the only ones in the past year to receive money from the National Health and Research Institute of Taiwan to establish a center.

"So it means this area has been acknowledged as a key research area for Taiwan," he said.

Among the hardware available to Niddam and his fellow researchers are six magnetic imaging resonance (MRI) machines as well as electroencephalography (EEG) and magnetoencephalography (MEG) machines.

EEGs and MEGs record from outside the brain. The EEG does so when the patient puts on a rather unfashionable Lycra cap with dozens of electrodes attached to it. The MEG has the patient sit in a room that has been shielded from the earth's magnetic forces and place their head in an inverted bowl.

The benefit of both the EEG and MEG is an ability to follow brain activity in real time, down to the millisecond. However, the machines cannot pinpoint where in the brain the activity is taking place to an area smaller than 100,000 or more brain cells.

With the MRI technology that looks deep into the brain, activity can be located to areas smaller than a millimeter, but cannot provide the temporal accuracy of an EEG or MEG. MRI works by tilting the spin of every atom in the body in the same direction, then sending pulses of radio waves into the scanner which knock the nucleus of each cell out of its proper alignment. When it realigns, it sends a signal which the scanner records, analyzes and drafts into an image.

Another form of MRI measurement, called a functional MRI, can measure brain activity by detecting oxygen levels in specific brain areas.

Niddam's colleague, Yeh Tzu-chen (葉子城), showed the MRI scan of a patient with a brain tumor. The functional MRI, he explained, is used not only to pinpoint the location of the tumor, but to discern what functions the areas of the brain beside the tumor control.

Because of the tumor's location on the left side of the patient's brain, there was a risk that surgery could leave the patient without the use of the right hand.

"During the MRI, I stood next to the patient and tapped on their foot," said Yeh, who is also an assistant professor in the Department of Radiology at National Yangming University Medical School. "They knew that when I did they should move their right hand. The MRI recorded exactly which part of the brain next to the tumor was responsible for moving the hand, creating an indispensable map for surgeons to use in removing the tumor."

"Remember those guys who invented [MRI] got the Nobel for it?" Niddam said, referring to American Paul C. Lauterbur and Briton Sir Peter Mansfield's 2003 prize. "Without it, diagnosis worldwide would be much less efficient."

The primaries for this year’s nine-in-one local elections in November began early in this election cycle, starting last autumn. The local press has been full of tales of intrigue, betrayal, infighting and drama going back to the summer of 2024. This is not widely covered in the English-language press, and the nine-in-one elections are not well understood. The nine-in-one elections refer to the nine levels of local governments that go to the ballot, from the neighborhood and village borough chief level on up to the city mayor and county commissioner level. The main focus is on the 22 special municipality

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invaded Vietnam in 1979, following a year of increasingly tense relations between the two states. Beijing viewed Vietnam’s close relations with Soviet Russia as a threat. One of the pretexts it used was the alleged mistreatment of the ethnic Chinese in Vietnam. Tension between the ethnic Chinese and governments in Vietnam had been ongoing for decades. The French used to play off the Vietnamese against the Chinese as a divide-and-rule strategy. The Saigon government in 1956 compelled all Vietnam-born Chinese to adopt Vietnamese citizenship. It also banned them from 11 trades they had previously

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful

Jan. 12 to Jan. 18 At the start of an Indigenous heritage tour of Beitou District (北投) in Taipei, I was handed a sheet of paper titled Ritual Song for the Various Peoples of Tamsui (淡水各社祭祀歌). The lyrics were in Chinese with no literal meaning, accompanied by romanized pronunciation that sounded closer to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) than any Indigenous language. The translation explained that the song offered food and drink to one’s ancestors and wished for a bountiful harvest and deer hunting season. The program moved through sites related to the Ketagalan, a collective term for the