It has already wooed and won millions of lonely hearts in Europe and the US. Now speed dating is sweeping Asia and making a dash for China in a bid to seduce the army of lonely hearts living in the world's most populous nation.

Speed dating is a system in which up to 50 single people are brought together in a club and have three minutes to meet each member of the opposite sex. So far, the first China franchises for the service are being sold in Shenzhen, Shanghai and Beijing.

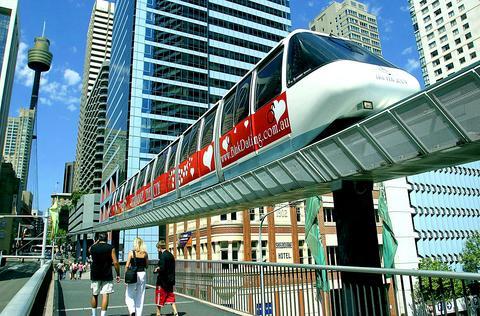

PHOTO: EPA

The romance deals are being brokered by Hong Kong-based WhirlWindDate, which has staged three speed dating evenings a month in Hong Kong since launching last August. The company has also sold a franchise for business in Singapore.

WhirlWindDate, which is modelled on speed dating companies that first made headlines in the US two years ago, is also seeking other franchise partners for similar operations in other major Asian cities such as Kuala Lumpur, Taipei and Bangkok.

"We know that there is no speed dating in China at the moment. Most people don't know what it is. So we think there is a huge potential market demand there," said general manager Cynthia Chan Kar-man.

Single people pay around US$40 for a ticket to the speed dating events, held in swanky clubs to bring together professional singles mostly aged between 25 and 45.

The system claims to take the embarrassment out of one-on-one meetings by creating a succession of brief encounters after which participants nominate the people they want to see again on a secret form.

If the forms match, the organizers send out e-mail addresses to the participants the following day so they can contact each other.

Companies like WhirlWindDate say speed dating increases the chances of single people finding a match -- although critics call the approach superficial and faddish.

Dating agencies are already widely used in China, and for centuries, couples have turned to traditional matchmakers to seek marriage partners. Chan said she thought that although people might initially be shy of the concept of speed dating, they would soon realize its advantages.

"People in China are getting more and more open and they are starting to realize that traditional methods aren't as effective," she said. "It tends to be very formal and the result may not be as good as speed dating where you get 20 or me people to meet at a time.

"Young people in places like Shenzhen and Shanghai are not actually too far removed from Hong Kong. There are so many links between Hong Kong and China that they might know about us and what we do already.

"These cities are cosmopolitan and similar to the culture of Hong Kong and the people there are well educated. Many of them are professional and they have spare money to enjoy their life and find partners."

Single people in China who sign up for speed dating will have their details put into the WhirldWindDate computer and will be able to meet Hong Kong singles online, raising the possibility of cross-border romances.

"I think that cross-border romances are very possible especially with young professionals in Shenzhen," said Wan. "A guy may find a girl who he thinks is very suitable for him even though she's on the other side of the border and they may try to meet up."

Toby Jones, founder of UK and Hong Kong online dating service www.wheresmydate.com.hk and a critic of speed dating, said he was also working on plans to expand his business to China.

However, he said franchising out the business carried risks. "I would do it with an office and a company up there," he said. "China is one of the biggest places around, revenue opportunities are great and you can't afford to give it away to people you don't know.

"The biggest loophole is that someone finds out about it and the next thing you know they do the same thing with a different name.

There are lots of trendy bars in Chinese cities that will latch onto this and just copy it.

"Speed dating is great at first but after a while it gets boring. It's been in Hong Kong for six to nine months now. Another six months and it'll just be part of the furniture, and people will want to move on to something new."

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.

It’s a bold filmmaking choice to have a countdown clock on the screen for most of your movie. In the best-case scenario for a movie like Mercy, in which a Los Angeles detective has to prove his innocence to an artificial intelligence judge within said time limit, it heightens the tension. Who hasn’t gotten sweaty palms in, say, a Mission: Impossible movie when the bomb is ticking down and Tom Cruise still hasn’t cleared the building? Why not just extend it for the duration? Perhaps in a better movie it might have worked. Sadly in Mercy, it’s an ever-present reminder of just