One of the effects of the 911 attacks was to wake up the distracted Western public to the horror of Taliban rule in Afghanistan. Now, with the Taliban out of power, Osama, the first film produced in Afghanistan since they took over in 1996, arrives to nudge us back into a state of alertness, and also, as remnants of the ousted regime continue to menace that nation's peace and stability, to trouble our sleep and our consciences as well.

Written and directed by Siddiq Barmak, an Afghan filmmaker trained in Moscow in the 1980s and clearly influenced by the Iranian humanist cinema of the 1990s, Osama begins with an apt epigraph from Nelson Mandela: "I can forgive, but I cannot forget."

Barmak is unsparing in his anatomy of the Taliban's cruelty, especially as it was directed against women, but there is very little feeling of vengefulness or hatred in the film, which makes it all the more devastating in the end.

PHOTOS COURTESY OF CROWN FILMS

The opening scenes, a kind of trompe l'oeil documentary within the movie whose meaning becomes clear only much later, capture the violent suppression of a women's-rights demonstration in the sandy, war-blasted streets of Kabul. A scared young girl (Marina Golbahari) watches from a doorway as Taliban soldiers, using water hoses, live ammunition and grenade launchers, scatter a crowd of women in blue and ocher burkhas.

This is only the most brutal and public manifestation of the pervasive terror under which women in Kabul must live. The hospital where the girl's mother works is raided, and the mother (Zubaida Sahar) is saved from arrest only when a man whose father is in her care says he is her husband. There is an almost absurd sadism to the Taliban's regulations of women's behavior. Even when a household includes no men -- hardly uncommon after so many years of war -- the women still may not be seen in public or earn a living. An uncovered foot or an unwelcome word can lead to harassment, or even severe

punishment.

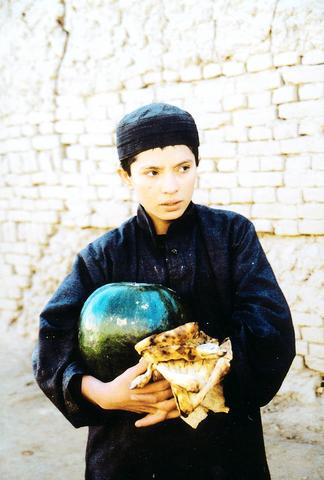

Despite all this injustice, the girl's kindly grandmother insists that the sufferings of men and women are equal because the sexes themselves are equal. This leads her to conclude that they may also be interchangeable, and so her granddaughter, with a short haircut and a dark skullcap, is sent out to work for a sympathetic shopkeeper. (She is later given the name Osama by a young beggar who knows the secret of her identity.) A similar masquerade was at the heart of Majid Majidi's film Baran, about an Afghan refugee in Tehran who disguised herself as a boy to work at a construction site.

Like Majidi, Barmak has a gently poetic visual sense: after her metamorphosis, one of the girl's severed braids is planted in a flower pot and watered by an intravenous drip her mother rescued from the shut-down hospital. He is also able to find moments of tenderness and humor in his bleak story. One sequence that stands out is a lesson in intimate hygiene taught to madrasa students by an elderly mullah -- a glimpse at the radical Islamist approach to sex education.

Barmak's patron was the Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf, whose Kandahar is set in Taliban-era Afghanistan and whose daughter Samira's At Five O'Clock in the Afternoon takes place in Kabul after the American-led rout of the Taliban. Some of the surrealist touches in Osama -- gorgeous, haunting images that call for an adjective like Makhmalbafian -- may be a result of this association, and the orange glow that suffuses the landscape in all three movies may owe something to the fact that they share the gifted cinematographer Ebrahim Ghafuri. This is not to take anything away from Barmak, who had the self-confidence to embark on this project with donated equipment, a tiny budget and a cast of nonprofessionals recruited from the streets of Kabul.

The mere existence of the movie, which received the Camera d'Or special mention for best first feature in Cannes last year and the Golden Globe for best foreign film last month, would be impressive enough. But the movie's power and coherence are such that you forget completely about the hard circumstances of its making, which is nothing short of astonishing.

There is not much overt or explicit violence in Osama, which opens today in Taiwan, but an unshakable dread shadows the bright alleyways of Kabul and seeps through the heavy wooden doors of the houses. Like The Pianist, Roman Polanski's tour of Nazi-occupied Warsaw, Osama is a meticulous and beautifully made inquiry into the ways that ideological evil can infect, and ultimately destroy, the intimacies and small pleasures of daily life.

Osama has no special resiliency or survival skills; her face is, at every moment, a study in suppressed panic and worried passivity. Her unvarnished vulnerability, along with the director's combination of tough-mindedness and lyricism, prevents the movie from becoming at all sentimental; instead, it is beautiful, thoughtful and almost unbearably sad.

It’s a good thing that 2025 is over. Yes, I fully expect we will look back on the year with nostalgia, once we have experienced this year and 2027. Traditionally at New Years much discourse is devoted to discussing what happened the previous year. Let’s have a look at what didn’t happen. Many bad things did not happen. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) did not attack Taiwan. We didn’t have a massive, destructive earthquake or drought. We didn’t have a major human pandemic. No widespread unemployment or other destructive social events. Nothing serious was done about Taiwan’s swelling birth rate catastrophe.

Words of the Year are not just interesting, they are telling. They are language and attitude barometers that measure what a country sees as important. The trending vocabulary around AI last year reveals a stark divergence in what each society notices and responds to the technological shift. For the Anglosphere it’s fatigue. For China it’s ambition. For Taiwan, it’s pragmatic vigilance. In Taiwan’s annual “representative character” vote, “recall” (罷) took the top spot with over 15,000 votes, followed closely by “scam” (詐). While “recall” speaks to the island’s partisan deadlock — a year defined by legislative recall campaigns and a public exhausted

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful