Throughout the Japanese invasion and the days of China's last emperors during the Qing Dynasty, Guan Daoli's Manchu family have resided in their quaint courtyard home in one of Beijing's central districts.

Even after the rampaging teenage Red Guards took over their spacious property during the chaotic Cultural Revolution in the 1960s, Guan's family managed to stay put, squeezed into two small rooms.

But wars and regime changes are proving no match for developers and the current Chinese government's mad rush to cash in on a property boom.

PHOTO: AFP

"They are demanding we sign the papers to move. They said they have to build offices here," Guan said.

"But this home was handed down to us by our ancestors. My grandfather, who was a Manchu official, lived here. We are private property owners. They should respect our rights."

The 70-year-old man and his 65-year-old wife might not have a choice.

All around them, families have been moved and demolition workers have wasted no time in turning their neighborhood into a wasteland of brick piles, fallen wooden beams, scattered glass and half-standing houses.

Across China's major cities, especially in the capital Beijing where the 2008 Olympic Games will be held, the government is forcing people living in centrally-located homes to make way for commercial and residential buildings.

Officials said the land is needed to build new offices for Beijing's procuratorate.

"All compensations are based on government regulations," said an official from the district government's suboffice in the neighborhood.

Critics say authorities use the excuse that the homes are old and dangerous, but are in fact hungry for the revenue they can rake in and the corruption money they can pocket by driving residents out to the suburbs and selling the land to developers.

Most residents grudgingly pack up, having no choice but to take a non-negotiable amount as compensation.

The stubborn ones must put up with cuts to electricity and water, wrecking crews who bulldoze up to their walls and front doors. Sometimes hired thugs intimidate people into moving by beating them with clubs at night.

But in the end, all except perhaps President Hu Jintao's (胡錦濤) great aunt have had to give in.

Hu's aunt Liu Bingxia, a tottering hunched-backed woman in her late 80s, managed to save the family's ancestral home in Taizhou, a city in east China's Jiangsu province, after she informed the bank that wanted to build there that her great nephew was then vice president.

Anxious to avoid potential offense, the bank decided on a bizarre architectural compromise and Hu's childhood home remains, locked-up and unused, inside the bank compound.

Ordinary people like Guan, however, have no recourse. And lawyers wil not waste time on the cases as the courts refuse to touch them. The Chinese media shy away from such stories.

Guan's home is one of six or seven still standing in the neighborhood, all that's left after homes for nearly 300 households and businesses there were razed.

Except for the two rooms and a hallway he and his wife occupy with their eldest son, almost every room in the 19-room two-story house has been emptied, their windows

knocked out.

"We don't agree to move. If we have to die here, we will," said Guan's wife Jin Xuefang.

Families like Guan's who own their property, unlike many of the residents who were assigned free housing after the communists took over in 1949, are usually the last to budge.

The family has been offered compensation of 200,000 yuan (US$24,000), which only accounts for the two rooms they occupy, not what they lost during the Cultural Revolution.

They said the amount is a pittance and not nearly enough for them to find suitable accommodation. Beijing's property prices mean they would have to move at least a couple of hours bus-ride away to the countryside to afford to buy a home with that money.

"There's no law to protect the rights of those being forced to move," said one of Guan's neighbors, who is also refusing to leave.

"It doesn't matter what project they're building, before they begin knocking down homes, they should work out a price that residents can accept."

His elderly mother standing nearby said, "They're worse than the Japanese," referring to the Japanese occupation during World War II.

US President Donald Trump may have hoped for an impromptu talk with his old friend Kim Jong-un during a recent trip to Asia, but analysts say the increasingly emboldened North Korean despot had few good reasons to join the photo-op. Trump sent repeated overtures to Kim during his barnstorming tour of Asia, saying he was “100 percent” open to a meeting and even bucking decades of US policy by conceding that North Korea was “sort of a nuclear power.” But Pyongyang kept mum on the invitation, instead firing off missiles and sending its foreign minister to Russia and Belarus, with whom it

When Taiwan was battered by storms this summer, the only crumb of comfort I could take was knowing that some advice I’d drafted several weeks earlier had been correct. Regarding the Southern Cross-Island Highway (南橫公路), a spectacular high-elevation route connecting Taiwan’s southwest with the country’s southeast, I’d written: “The precarious existence of this road cannot be overstated; those hoping to drive or ride all the way across should have a backup plan.” As this article was going to press, the middle section of the highway, between Meishankou (梅山口) in Kaohsiung and Siangyang (向陽) in Taitung County, was still closed to outsiders

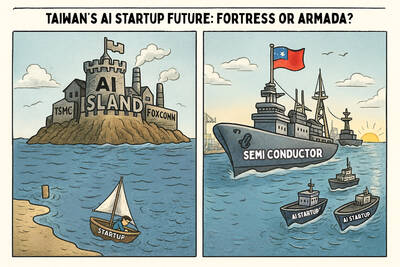

President William Lai (賴清德) has championed Taiwan as an “AI Island” — an artificial intelligence (AI) hub powering the global tech economy. But without major shifts in talent, funding and strategic direction, this vision risks becoming a static fortress: indispensable, yet immobile and vulnerable. It’s time to reframe Taiwan’s ambition. Time to move from a resource-rich AI island to an AI Armada. Why change metaphors? Because choosing the right metaphor shapes both understanding and strategy. The “AI Island” frames our national ambition as a static fortress that, while valuable, is still vulnerable and reactive. Shifting our metaphor to an “AI Armada”

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has a dystopian, radical and dangerous conception of itself. Few are aware of this very fundamental difference between how they view power and how the rest of the world does. Even those of us who have lived in China sometimes fall back into the trap of viewing it through the lens of the power relationships common throughout the rest of the world, instead of understanding the CCP as it conceives of itself. Broadly speaking, the concepts of the people, race, culture, civilization, nation, government and religion are separate, though often overlapping and intertwined. A government