This is a serious, ground-breaking and finally brilliant novel by one of China's leading authors. Laid out in the form of a dictionary of the dialect spoken in a minute part of southern China, A Dictionary of Maqiao quickly develops into a story of the lives of a group of so-called "educated youth" dispatched to such remote regions during China's Cultural Revolution.

Much of it is in fact the story of Han Shaogong's own experience. The result is a masterpiece, and at the same time a clarion call in defense of the local and particular as against the international and the uniform.

For Han to call it a "dictionary" is to stretch the term, to put it mildly. Each word, rather, acts as a stimulus to provoke seemingly random thoughts on the subject referred to, a process aided by the words not being in Western alphabetical order. So you begin with "River," then a particular river, then a term used to describe the local rustic population -- and before you know where you are you are listening to a tale of how a group of urban youth once tried to cheat a ferryman of his fare, and on another occasion threw a gun they shouldn't have possessed down into the mud, and so on. After only a few pages an array of characters has been established, and their interactions begin to constitute the material of an almost conventional story.

This method, as the translator Julia Lovell comments, actually harks back to the traditional Chinese literary form of the "jottings" (biji) essay -- loosely connected thoughts prompted by a particular idea or quotation. There are European precedents too. The penultimate section of Joyce's Ulysses is one example in English, as are all the many long fictions, such as Don Quixote or Gargantua and Pantagruel, that proceed by episodes, digressions, and animadversions irregularly inserted on any subject under the sun.

A Dictionary of Maqiao conjures up once again the world of remote upland China made familiar in so many other novels written by former "educated youth" about their experiences. Rain falls for days on end, winds howl, people find shelter from evil spirits in thatched huts and have long been conditioned to eating the most abominable horrors. Yet today the former urban evacuees remain ambivalent, continuing to feel that their tame life back in the cities has never attained quite the same level of memorability.

The meeting of two such different forms of sensibility lies at the heart of the novel's method. The migrants tend not to have much religious belief, have more or less ingested Maoist orthodoxy, however grudgingly, and approach problems with a generally rational outlook.

The locals, by contrast, embody as weird a collection of attitudes as you could imagine. Imported novelties such as dangerous agricultural pesticides and Communist Party hierarchies are treated with equal wonder and puzzlement. Their patched-up, hand-to-mouth world had had its own bizarre coherence, and these new intrusions, which the city youth understand and accept, give rise to comic contortions of resentment and adaptation in the peasants.

An example of the episodic technique is the entry under the headword "This him." This refers to a Maqiao word meaning "someone here, standing in front of you," and distinct from another word meaning "someone not here, someone far away."

Han, however, raises his definition to an intense pitch of emotion by using it as a pretext to describe an incident involving an ultra-humble character, Yanzao. He is someone who is given all the most menial tasks, things even more disgusting than the norm in that deprived and forsaken village. Han returns after many years and asks after him. That evening he shows up from many miles away, carrying a huge log on his shoulder. In the event they barely talk.

Han feels disgusted at Yanzao's swollen gums, the bulging veins in his neck, his grunts and his sour country smell. After half an hour they part, but as Yanzao leaves, Han catches sight of a tear in the corner of his eye. Among all the pressures of city literary life, he writes, whether sleeping or awake, he can't forget that tear. It's the difference between the Maqiao words for the man who's far away, and the one who's real, present, and standing crying in front of you. It's the difference between an abstract idea of backward peoples, and the reality of their poverty, their need, and their inability to escape who they are.

In an important Afterword, Han comments on how differences of language define people, giving character to not only regions but also to generations. The people of Hainan Island, he points out, have what is perhaps the largest fish-related vocabulary in the world. Yet when he asked one market salesman to identify an item in Mandarin, all the Hainan man could come up with was "big sea fish."

Not only was the fish's identity blurred and diminished by the man having to speak Mandarin, Han asserts -- so was the speaker's.

When it first appeared in Chinese in Taiwan, this book won the China Times Best Novel award, and has elsewhere been cited as one of the Top 100 works of 20th century Chinese fiction. It was first published in English last month.

It would be a pity if, at a time when foreign-language films as well as translated books are reportedly becoming harder and harder to sell to the American public, this magnificent fictional work was left gathering dust on bookstore shelves. It's that rare pleasure, something that is both of high quality and yet at the same time readable and enjoyable. The translation is everywhere excellent - -- fluent, colloquial where appropriate, without being excessively so, learned in places, and without any hint anywhere of "translationese."

This is a wonderful book, surely destined for classic status. When you start it you think it's just the working out of a clever idea. But in the event the depths it touches are extraordinary.

Has the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) changed under the leadership of Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌)? In tone and messaging, it obviously has, but this is largely driven by events over the past year. How much is surface noise, and how much is substance? How differently party founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) would have handled these events is impossible to determine because the biggest event was Ko’s own arrest on multiple corruption charges and being jailed incommunicado. To understand the similarities and differences that may be evolving in the Huang era, we must first understand Ko’s TPP. ELECTORAL STRATEGY The party’s strategy under Ko was

Before the recall election drowned out other news, CNN last month became the latest in a long line of media organs to report on abuses of migrant workers in Taiwan’s fishing fleet. After a brief flare of interest, the news media moved on. The migrant worker issues, however, did not. CNN’s stinging title, “Taiwan is held up as a bastion of liberal values. But migrant workers report abuse, injury and death in its fishing industry,” was widely quoted, including by the Fisheries Agency in its response. It obviously hurt. The Fisheries Agency was not slow to convey a classic government

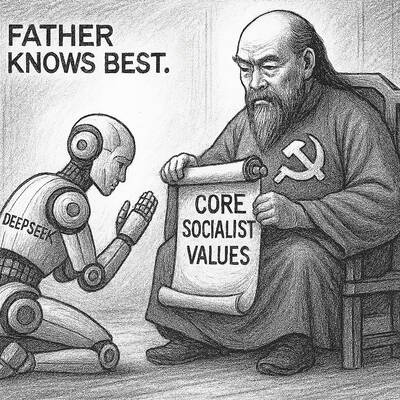

It’s Aug. 8, Father’s Day in Taiwan. I asked a Chinese chatbot a simple question: “How is Father’s Day celebrated in Taiwan and China?” The answer was as ideological as it was unexpected. The AI said Taiwan is “a region” (地區) and “a province of China” (中國的省份). It then adopted the collective pronoun “we” to praise the holiday in the voice of the “Chinese government,” saying Father’s Day aligns with “core socialist values” of the “Chinese nation.” The chatbot was DeepSeek, the fastest growing app ever to reach 100 million users (in seven days!) and one of the world’s most advanced and

It turns out many Americans aren’t great at identifying which personal decisions contribute most to climate change. A study recently published by the National Academy of Sciences found that when asked to rank actions, such as swapping a car that uses gasoline for an electric one, carpooling or reducing food waste, participants weren’t very accurate when assessing how much those actions contributed to climate change, which is caused mostly by the release of greenhouse gases that happen when fuels like gasoline, oil and coal are burned. “People over-assign impact to actually pretty low-impact actions such as recycling, and underestimate the actual carbon