Musician Joe Wang (王明輝) remembers 1989 well. Political demonstrations brought turmoil to Taiwan society. Long-suppressed social forces were being released from long-term dictatorship. And the first official opposition party -- the DPP -- was using a strategy of protest to clash with the KMT regime.

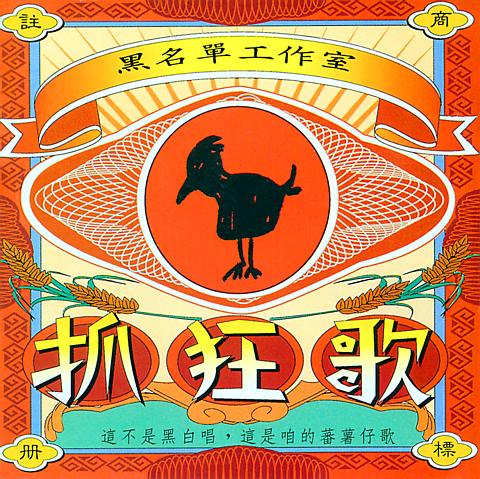

It was also the year that an unprecedented Taiwanese language album appeared on the market, titled Songs of Madness (抓狂歌) and subtitled "These aren't crap songs, these are our yam songs" (yam is a symbol of Taiwan). It was produced by Black List (黑名單工作室) -- comprised of Wang, Io Chen (陳主惠) and Keith Stewart from the US. The album recruited then underground singers such as Chen Ming-chang (陳明章) and Lin Wei-tseh (林瑋哲). The "mad songs" in the album mainly satirized the political situation at that time and ridiculed people's powerlessness in a hyper but chaotic society.

For example, in "Democracy Bumpkin" (民主阿草):

I went strolling in the morning, seeing troops of armed policemen, wondering if they were preparing to fight communists.

My neighbor told me it was against protesters. He said he is something called DPP and it's fun to protest.

There were a bunch of old guys occupying seats in the congress, using our tax money for their medical fees. There were old mainlanders serving the country for 40 years but gaining nothing. I want to protest. I want to protest, they shouted.

"We wanted to record the happenings of Taiwan's society and provide a space for people to think -- through music," Wang recalls. When it comes to protest singers or bands, one might think of Bob Dylan in the 60s, the UK's Billy Bragg in the 80s or Rage Against the Machine in the 90s. In Taiwan, in the late 80s and early 90s, it was Black List and its frontman Joe Wang.

For Wang, Black List's role was to find a way for intellectuals to intervene through music. "Since Lo Ta-yu (羅大佑) in the early 80s, [who sang "Lukang Small Town"], we had not heard an intellectual's voice in the music scene," he says. "For us, we didn't quite believe in sentimental inspiration when we wrote music."

Songs of Madness breaks down the convention of Taiwanese language pop songs, which contain exaggerated elements of lament, either about lost love or good times that can't be relived. But Black List's social criticism cloaked in cynical Taiwanese rap and folk songs, which soon became popular among college students and young middle class. Songs of Madness was labeled by media and critics as the New Taiwanese Songs. Soon, Chen Ming-chang and Lin Wei-tseh became popular songwriters and producers. Chen wrote and produced many award-winning scores for director Ho Hsiao-hsien (侯孝賢) and Lin is now producer of the award-winning singer Faith Yang (楊乃文). But for Wang, who insists on staying aloof from the mainstream, he knew that the New Taiwanese Song movement was no more than a market gimmick. "After Chiang Hui (江蕙) swept away KTV hit rate, the mainstream started to embrace sentiment ballads again," he said.

Wang didn't stop producing alternative music during the 10 years following Songs of Madness, a period during which his star has slowly dimmed. Gradually, Taiwanese language diminished as an essential tool of protest, so Wang shifted his focus to other subjects of social struggle -- for instance, labor and aboriginal issues. "We [Black List] are the only group who cares about the issue of class in Taiwan society," Wang says.

Words of the Year are not just interesting, they are telling. They are language and attitude barometers that measure what a country sees as important. The trending vocabulary around AI last year reveals a stark divergence in what each society notices and responds to the technological shift. For the Anglosphere it’s fatigue. For China it’s ambition. For Taiwan, it’s pragmatic vigilance. In Taiwan’s annual “representative character” vote, “recall” (罷) took the top spot with over 15,000 votes, followed closely by “scam” (詐). While “recall” speaks to the island’s partisan deadlock — a year defined by legislative recall campaigns and a public exhausted

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the

The primaries for this year’s nine-in-one local elections in November began early in this election cycle, starting last autumn. The local press has been full of tales of intrigue, betrayal, infighting and drama going back to the summer of 2024. This is not widely covered in the English-language press, and the nine-in-one elections are not well understood. The nine-in-one elections refer to the nine levels of local governments that go to the ballot, from the neighborhood and village borough chief level on up to the city mayor and county commissioner level. The main focus is on the 22 special municipality