Europe’s political forces are divided between those who regard the EU as promoting unfair, inefficient neoliberal economic policies, and those who see the bloc as key to preserving the relatively equitable and inclusive “European social model.”

Yet the recent European Parliament election featured little debate about this model and generated few ideas for what policymakers should do to tackle income inequality across the continent.

That is a pity. Comparisons of income growth and inequality in Europe and the US over the past four decades have yielded important new insights into why incomes are far more evenly distributed in Europe than in the US, and about what each side of the Atlantic could learn from the other.

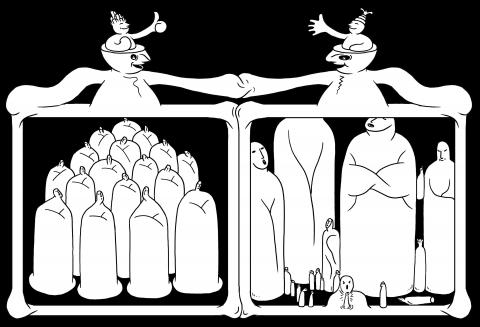

Illustration: Mountain People

Overall, US incomes have grown faster than those in Europe over the past 40 years. Between 1980 and 2017, average national income per adult grew 65 percent in the US, compared with 51 percent in Europe. The difference largely, though not entirely, reflects the EU’s failure to coordinate a continent-wide economic stimulus following the 2007-2008 financial crisis.

Compared with Western Europe, which subsequently suffered a lost decade (2007-2017) in which average national income per adult grew by less than 5 percent, the US grew five times faster.

However, these average growth rates conceal the extent to which income inequality has exploded in the US over the past four decades, while remaining far less extreme in Europe.

Although the average pre-tax income of the top 50 percent of US earners has more than doubled since 1980, that of the bottom half has grown by just 3 percent.

In Europe, on the other hand, the pre-tax income of the bottom half of the population grew by 40 percent over the same period — more than 10 times faster than for their US counterparts — although still below overall average European income growth.

Differences between US and European tax and transfer systems do not significantly change the overall picture. After taking these into account, the post-tax incomes of the bottom 50 percent have grown by a modest 14 percent in the US since 1980 — still way below overall income growth — and by up to 40 percent in Europe.

Economists often attribute rising inequality to technological change or growth in international trade. Yet this does not explain the sharply divergent inequality trends over the past 40 years in the US and Europe, because both experienced similar technological shocks and faced increased competition from developing countries over that period.

Instead, the contrast between Europe and the US reflects different policy choices.

Policymakers have two broad options for tackling income inequality:

Predistribution aims to create the conditions for a more even distribution of income in the future — through investments in healthcare and education, effective antitrust laws and labor-market regulations, and relatively strong labor unions, for example.

Redistribution of income, meanwhile, aims to reduce current inequalities through progressive taxation — whereby richer people pay higher rates of tax — and social transfers to the poorest.

Europe’s lower levels of inequality are not a consequence of more redistributive tax policies. True, the top marginal rate of US federal income tax has fallen from an average of 80 percent in 1950-1980 to 37 percent today, and US President Donald Trump lowered the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent in his Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017.

However, Europe’s corporate tax rates have also plunged, from an average of 50 percent in 1980 to 25 percent today — thereby benefiting richer citizens who increasingly rely on personal shareholdings for their income.

Moreover, taxes on consumption, which impose a proportionately greater burden on the poor, increased significantly in Europe over the same period.

Taxation systems in both the US and Europe, therefore, have generally become less progressive in recent decades. If anything, the US’ tax system is now slightly more progressive than Europe’s, but US inequality is nonetheless far greater.

The World Inequality Lab’s How Unequal Is Europe? report suggests that Europe’s more equal income distribution is largely the result of predistributive policies such as national minimum wages, greater worker protections, and free access to public education and healthcare.

Yet progressive taxation is still key to reducing both post and pre-tax income inequality. High marginal tax rates, for example, can help to limit unequal capital accumulation today and therefore make future income flows more equitable.

More fundamentally, progressive taxes are essential for the political sustainability of countries’ fiscal systems. The “yellow vest” protests that began in France in November last year — and appeared elsewhere in Europe thereafter — were initially ignited by a feeling of tax injustice.

Finally, progressive taxation also plays a predistributive role in Europe by helping to finance universal public education and healthcare programs. These in turn promote greater equality of opportunity and thus more equal distribution of income later on. The danger, therefore, is that the general trend toward less progressive tax systems would make it harder for Europe and the US to contain inequality in the future.

However, this is not inevitable. Perhaps US voters might become keener on free public education and healthcare if they see how these have supported rather than hampered economic growth in Europe. And Europe might draw inspiration from how the US government largely ended tax competition between states a century ago by introducing federal corporate and income taxes.

If Europe and the US can learn from each other in this way, radical-sounding approaches to tackling inequality might start to look more pragmatic and feasible on both sides of the Atlantic. And the next four decades might be less unequal than the previous four.

Thomas Blanchet is statistical tools and methods coordinator at the World Inequality Lab at the Paris School of Economics. Lucas Chancel, codirector of the lab, is a lecturer at Sciences Po and a research fellow at the Institute for Sustainable Development and International Relations. Amory Gethin is a research fellow at the lab.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

The US Senate’s passage of the 2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), which urges Taiwan’s inclusion in the Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercise and allocates US$1 billion in military aid, marks yet another milestone in Washington’s growing support for Taipei. On paper, it reflects the steadiness of US commitment, but beneath this show of solidarity lies contradiction. While the US Congress builds a stable, bipartisan architecture of deterrence, US President Donald Trump repeatedly undercuts it through erratic decisions and transactional diplomacy. This dissonance not only weakens the US’ credibility abroad — it also fractures public trust within Taiwan. For decades,

In 1976, the Gang of Four was ousted. The Gang of Four was a leftist political group comprising Chinese Communist Party (CCP) members: Jiang Qing (江青), its leading figure and Mao Zedong’s (毛澤東) last wife; Zhang Chunqiao (張春橋); Yao Wenyuan (姚文元); and Wang Hongwen (王洪文). The four wielded supreme power during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), but when Mao died, they were overthrown and charged with crimes against China in what was in essence a political coup of the right against the left. The same type of thing might be happening again as the CCP has expelled nine top generals. Rather than a

Former Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmaker Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) on Saturday won the party’s chairperson election with 65,122 votes, or 50.15 percent of the votes, becoming the second woman in the seat and the first to have switched allegiance from the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) to the KMT. Cheng, running for the top KMT position for the first time, had been termed a “dark horse,” while the biggest contender was former Taipei mayor Hau Lung-bin (郝龍斌), considered by many to represent the party’s establishment elite. Hau also has substantial experience in government and in the KMT. Cheng joined the Wild Lily Student

Taipei stands as one of the safest capital cities the world. Taiwan has exceptionally low crime rates — lower than many European nations — and is one of Asia’s leading democracies, respected for its rule of law and commitment to human rights. It is among the few Asian countries to have given legal effect to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant of Social Economic and Cultural Rights. Yet Taiwan continues to uphold the death penalty. This year, the government has taken a number of regressive steps: Executions have resumed, proposals for harsher prison sentences