As world leaders landed in Papua New Guinea (PNG) for a Pacific Rim summit, the welcome mat was especially big for China’s president.

A huge sign in the capital, Port Moresby, welcomed Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平), picturing him gazing beneficently at Papua New Guinea’s leader, and his hotel was decked out with red Chinese lanterns.

China’s footprint is everywhere, from a showpiece boulevard and international convention center built with Chinese help to bus stop shelters that announce their origins with “China Aid” plaques.

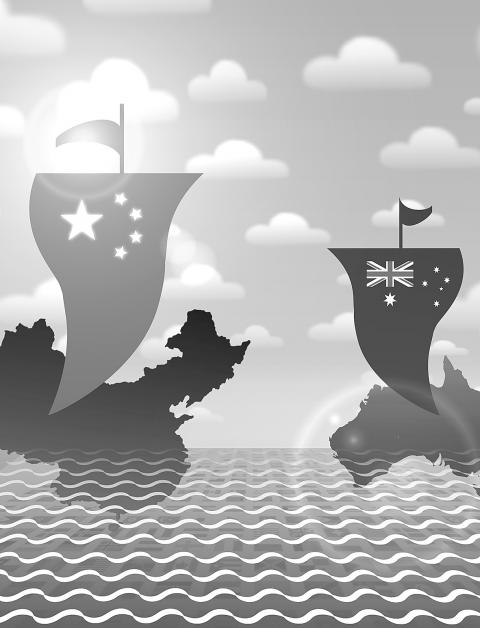

Illustration: Yusha

On the eve of Xi’s arrival for a state visit and the APEC meeting, newspapers ran a full-page statement from the Chinese leader. It exhorted Pacific island nations to “set sail on a new voyage” of relations with China, which in the space of a generation has transformed from the world’s most populous backwater into a major economic power.

With both actions and words, Xi has a compelling message for the South Pacific’s fragile island states, long both propped up and pushed around by US ally Australia: They now have a choice of benefactors.

With the exception of Papua New Guinea, those island nations are not part of APEC, but the leaders of many of them traveled to Port Moresby and were to meet with Xi.

Meanwhile, the APEC meeting was Xi’s to dominate. Headline-hogging leaders such as Russian President Vladimir Putin and US President Donald Trump did not attend.

Trump’s stand-in, US Vice President Mike Pence, stayed in Cairns in Australia’s north and flew into Papua New Guinea each day. New Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison, the nation’s fifth leader in five years, is barely known abroad.

“President Xi Jinping is a good friend of Papua New Guinea,” Papua New Guinean Prime Minister Peter O’Neill told reporters. “He has had a lot of engagement with Papua New Guinea and I’ve visited China 12 times in the last seven years.”

Pacific island nations, mostly tiny, remote and poor, rarely figure prominently on the world stage, but have for several years been diligently courted by Beijing as part of its global effort to finance infrastructure that advances its economic and diplomatic interests.

Papua New Guinea with about 8 million people is by far the most populous, and with its extensive tropical forests and oil and gas reserves, is an obvious target for economic exploitation.

Six of the 16 Pacific island states have diplomatic relations with Taiwan, a sizeable bloc within the rapidly dwindling number of nations that recognize the nation. Chinese aid and loans could flip those six into its camp.

A military foothold in the region would be an important geostrategic boost for China, though its purported desire for a base has so far been thwarted.

Beijing’s assistance comes without the oversight and conditions that Western nations and organizations such as the World Bank or the IMF impose. It is promising US$4 billion of finance to build the first national road network in Papua New Guinea, which could be transformative for the mountainous nation, but experts warn there could also be big costs later on: unsustainable debt, white elephant showpieces and social tensions from a growing Chinese diaspora.

“China’s engagement in infrastructure in PNG shouldn’t be discounted. It should be encouraged, but it needs to be closely monitored by the PNG government to make sure it’s effective over the long term,” said Jonathan Pryke, a Papua New Guinea expert at the Lowy Institute, a think tank in Sydney. “The benefits of these projects, because a lot of them are financed by loans, only come from enhanced economic output over a long time to be able to justify paying back these loans.”

“The history of infrastructure investment in PNG shows that too often there is not enough maintenance going on,” Pryke said. “There’s a build, neglect, rebuild paradigm in PNG as opposed to build and maintain, which is far more efficient.”

Some high-profile Chinese projects in Papua New Guinea have already run into problems.

A promised fish cannery has not materialized after several years and expansion of a port in Lae, the major commercial center, was botched and required significant rectification work.

Two of the Chinese state companies working in the nation, including the company responsible for the port expansion, were until recently blacklisted from World Bank-financed projects because of fraud or corruption.

Xi’s newspaper column asserted China is the biggest foreign investor in Papua New Guinea, a statement more aspirational than actual. Its involvement is currently dwarfed by the investment of a single company — ExxonMobil’s US$19 billion natural gas extraction and processing facility.

Australia, the former colonial power in Papua New Guinea, remains its largest donor of conventional foreign aid.

Its assistance, spread across the nation, and aimed at improving bare-bones public services and the capacity of government, is less visible, but its approach is shifting in response to China’s moves.

In September, the Australian government announced it would pay for what is typically a commercial venture — a high-speed undersea cable linking Australia, Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, that promises to make the Internet and telecommunications in the two island nations faster, more reliable and less expensive.

Earlier this month, Australia announced more than US$2 billion of funding for infrastructure and trade finance aimed at Pacific island nations and also agreed to the joint development of a naval base in Papua New Guinea, heading off feared Chinese involvement.

It is also boosting its diplomatic presence, opening more embassies to be represented in every Pacific island state.

“The APEC meeting is shaping up to be a face-off between China and Australia for influence in the Pacific,” Human Rights Watch Australia director Elaine Pearson said.

That might seem a positive development for the region, but Pearson cautioned that competition for Papua New Guinea’s vast natural resources has in the past had little positive impact on the lives of its people.

“Sadly, exploitation of resources in PNG has fueled violent conflict, abuse and environmental devastation,” she said.

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s