Ivory is the cocaine of Southeast Asia — millions of people demand it and the world thinks it can stop them by banning supply. The world is wrong.

On Thursday last week, the central London conference of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), a world wildlife organization, saw panjandrums from 46 countries meet with British royalty in the painted halls of Lancaster House. Previous Lancaster House conferences liberated Africans from bondage, but this one put them back. The Prince of Wales and the Duke of Cambridge pledged to “end the ivory trade” and “secure the future of these iconic species,” notably the rhinoceros and the elephant. Never were words so futile.

The futility would not matter if it were not so counterproductive. CITES is to wildlife what the US Drug Enforcement Administration is to narcotics. CITES secretary-general John Scanlon talks like a hardline cop about the need for ever more “undercover operations and harsher penalties,” but however many non-governmental organizations and bureaucrats it takes to fill a luxury hotel, one cannot defy the law of economics: Demand cannot be stifled by banning supply. All that does is raise the price. One rhinoceros horn can be worth as much as US$300,000, a figure that is a death sentence on every rhino.

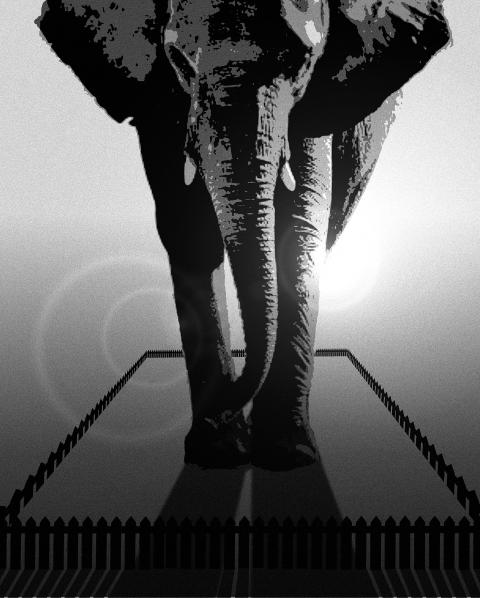

Illustration: Yusha

Few people care deeply enough about distant wildlife to challenge those who offer to make them feel good. Hence the ghoulish public relations exercises that precede CITES’ conferences of members destroying quantities of ivory in fires and crushers. This time, US President Barack Obama ordered the US to crush 5.4 tonnes and China duly crushed the same, while France crushed 2.7 tonnes. This appalling waste merely increases poachers’ profits and insults Africa, to which the value of the ivory properly belongs. It is like medieval princes burning food to taunt starving subjects.

When CITES first began flexing its muscles in the 1980s, an argument took place between ivory-producing southern Africa and Western wildlife charities. The African countries — notably South Africa, Namibia and Tanzania — argued that conservation was best achieved if locals had a vested interest in it, whether from tourism, controlled hunting or ivory sales. As long as people craved ivory, the alternative was massive poaching.

In his book, At the Hand of Man, US writer Raymond Bonner describes how US charity fundraisers overwhelmed African nations. Big money required “charismatic megaspecies” to be saved from imminent extinction, so the elephant was declared endangered when it was not. Furthermore, the world was flooded with pictures of mangled animals and in 1989, the trade in ivory and horn was banned.

Every prediction made by the African countries was right: Prices soared and in 10 years, elephant numbers halved and have continued to plunge by another two-thirds. An estimated 22,000 African elephants are killed annually in industrial massacres and the Asian elephant faces extinction. Rhino deaths have gone from a handful a year to more than 1,000, with their horns the same price per kilogram as gold.

It is hard to think of a more desperate failure of world government. Yet those responsible gather at Lancaster House to call for more of the same. Reducing consumption of any product requires reducing demand. Birds of paradise were hunted close to extinction until they went out of millinery fashion. Ivory demand did decline in Japan in the 1980s and China in the 1990s, leading to lower prices and less poaching, but the market soon recovered with economic liberation. Illegal suppliers now hold 90 percent of the Chinese market and rule their empires like Afghan drug lords.

The survival of wild animals depends entirely on those among whom they live. Elephants eat up to 453kg of vegetation a day and in India, kill up to 200 people a year. They may be glorious creatures, but they are destroying their ever-shrinking habitats. Unless local people want to save them, they will be poached to the point where just a few remain in fortified reserves.

The movement for African “community conservation” gained ground in the 1990s, with such ventures as Campfire in Zimbabwe and regulated hunting in Tanzania and Namibia. However, it has gained little purchase with Western conservationists. The director of wildlife for the Tanzanian Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism, Alexander Songorwa, had to plead with the US in the New York Times recently “on behalf of my country and all our wildlife” to not ban trophy hunting. The US$75 million revenue gained from the practice supports 26 game reserves.

Meanwhile, Namibia auctions up to five aging rhinos a year for culling, which recently fetched US$350,000 each. This is far more than photography tourism could ever generate and goes straight into wildlife protection and breeding. While more than 1,000 rhinos a year are reportedly poached in South Africa, Namibia’s rhinoceros population is rising.

Still, the auctions are vilified in the US. Richard Conniff, author of The Species Seekers, wonders that Americans who struggle to preserve the prairie dog “should be telling Namibians how to run their wildlife.”

However, hunting will not deliver the sort of money for conservation that could come from sales. CITES has an example of this in the killing of wild crocodiles, a practice that has virtually ceased since demand for skins is being met by captive breeding. South African conservationist Michael ‘t Sas-Rolfes has already made a powerful case for “ranched horn” from rhinos to underpin their protection.

Vague promises to get tough with ivory and horn dealers will have no more impact than getting tough with drug manufacturers. Animals will not be protected in the wild unless some value can be imputed to them and if this is not done, they will go the way of the European bear and the American bison. That value must accrue to those who alone can save them: Africa’s hard-pressed farmers, now increasingly inclined to turn to poaching. They and China’s consumers have a shared interest in wildlife conservation, so why criminalize them both?

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s