When I arrived with my mother in Rotterdam in the late 1970s, we thought we had found a safe haven. Coming from the sharp-edged mountains of north Morocco, the streets of the Low Countries felt like a place where everything could be done better. It did not seem possible that, 30 years later, the likes of Member of Parliament Geert Wilders of the Party for Freedom would wield influence, pushing his ban on the burqa, but then there were no burqas to be seen in the street.

The Netherlands felt like a country that would never betray me. I was greeted with enthusiasm at kindergarten; my name was the longest among the pupils and it was assumed I was very proud of that. Dutch culture was like a tattoo being imprinted on my brown skin. I learned the language and delighted in excelling at it in front of my teachers. I was their dream of multiculturalism: a foreigner who showed he could adapt to their culture through language. The mothers of classmates would inform me that they loved Moroccan cuisine, especially couscous. They would speak vividly, romantically about foreign cultures such as mine, and I felt proud.

The fact that I was different made me feel special and the Dutch created wonder in me as a child. They tolerated their dogs on their couches; they gave generously to faraway peoples suffering from disaster and sickness. I didn’t only read fairy tales, I lived one.

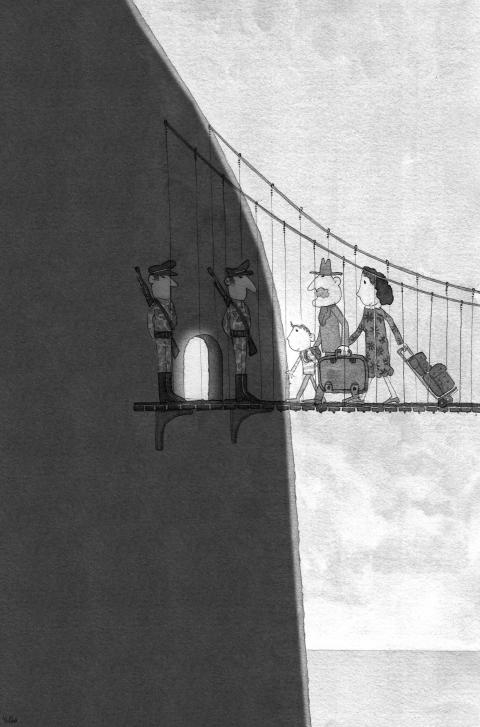

Illustration: Yusha

Then came the fall of the Berlin Wall, the 1990s and change. Europe decided it needed immigrants. The first change I saw was at home. My parents, growing older, gave up hope of the family returning to Morocco. Slowly, the feeling took over that we were here to stay, maintaining the privileges and opportunities of living in Europe. With that came the unease that their children would lose their identity. Already, we spoke Dutch, not Berber.

Meanwhile, the Dutch were waking up to the reality that most immigrants would never go back. Friday evening in Rotterdam saw large groups of immigrant children in the streets, estranged from their roots, trying to find solace in consumerism and urban culture, but also feeling alienated from Dutch society. Turks hung out with Turks, Moroccans with Moroccans. The melting pot didn’t heat up, the elements weren’t mixing. In my neighborhood, former convicts stopped me to talk about Islam. They felt that my staunchly secular lifestyle would not only bring disaster to me, but also to the spiritual community of Islam. A young friend introduced me to his uncle who had just come back from Afghanistan. He was a mujahidin.

I failed to see the shift. Immigrants had been seen by most Dutch as a marginal, colorful people from whose shops they could buy their meat and vegetables at ridiculously low prices. I knew this because my father had a butcher’s shop and I would sell them their lamb chops. As the 1990s progressed, the difference between allochtoon — one “originating from another country” — and autochtoon — “one originating from this country” began to be emphasized.

Allochtoon started becoming synonymous for criminality, big families, bad living and Islam. This wasn’t restricted to Holland. In Germany, questions were being raised about Turkish immigrants adhering to a fundamentalist Islam. Thousands of young French-Algerian football fans stormed the pitch when France played Algeria, their way of saying: “We don’t feel we belong in this country.”

So what had changed? I believe it was memories of war. The mass destruction of its people had given Europe a self-image as an intolerant, cruel continent. The deep feeling of guilt toward the victims had to be made good in the attitude towards new immigrants. The immigrant became a totem of the left-wing elite, of which there could be no criticism. Multiculturalism became the catchphrase.

In the banlieues of Paris, young immigrant girls could not go out in the evening for fear of being beaten by their brothers. No criticism. Immigrants from west Africa could keep four women in the same quarters. The elite did not intervene, for this was their culture. Society leaders believed that over time these immigrants would assimilate. A Moroccan would become Dutch, an Algerian French, a Turk Swedish.

This did not happen. They did the reverse. This was the moment the fear crept in, threatening the idea that Europe could assimilate its new citizens. If these immigrants adhered to their practices and rituals such as slaughtering their sheep on the balcony and not allowing their girls to go to school, Europe was being undermined from the inside.

It is in this context that Wilders can proclaim that there is no moderate Islam, that any Muslim who calls himself a Muslim will one day become radicalized. This is not just a trick of words; when Dutch people who voted for Wilders looked out of the window, they really had this feeling that their Muslim neighbors were becoming more Muslim, not less. They saw girls in burqas, proclaiming that this was an individual decision strengthening their spiritual relationship with Allah.

The burqa worried me too, but I saw Wilders’ move as a dangerous way of turning populist sentiment into cold-blooded politics and creating a new sort of fear.

The place of World War II in all this is growing more complicated. Populist parties in the Netherlands, Denmark and France are linking Islamist ideology to fascism. Islam is the new Nazism and Mohammed is their Adolf Hitler. History has become a blueprint for a new history: the world war against Islam.

In the 1980s, this message would have made people laugh, but not now. Look around. In Sweden, the debate around Islam and migration is growing in urgency, and Islam is just a particularly toxic element in the anti-immigrant movement. French President Nicolas Sarkozy, who is part Jewish, is throwing out the Roma. In Germany, the country of the Holocaust, a former head of the Bundesbank, Thilo Sarazzin, is making a plea for reducing working-class immigrants because of their “low IQ.”

The idea that Europe is being kidnapped by an ever-growing non-Western population is creating fear and populist parties are winning — but it will be -impossible to stop migration. European populations are growing older, the work forces shrinking. However, speaking in favor of migration — passionately, because I am a child of migration and make literature out of all its painful and comical contradictions — has become a form of blasphemy.

Certainly there is something rotten in multiculturalism, but turning the stereotypical victim into the stereotypical scapegoat is cheap and does not do justice to reality. I know that the Netherlands of my childhood will never come back. We are entering a dark period. A generation is growing up with xenophobia and the fear of Islam has become mainstream.

It’s time to come up with a new idea of what Europe is, drawing on the humane Europe as defended and described by writers such as Thomas Mann and Bertol Brecht. A Europe that newcomers consider a refuge, not a hell. If not, Europe will not die for a lack of immigrants, it will die for lack of light.

When it became clear that the world was entering a new era with a radical change in the US’ global stance in US President Donald Trump’s second term, many in Taiwan were concerned about what this meant for the nation’s defense against China. Instability and disruption are dangerous. Chaos introduces unknowns. There was a sense that the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) might have a point with its tendency not to trust the US. The world order is certainly changing, but concerns about the implications for Taiwan of this disruption left many blind to how the same forces might also weaken

As the new year dawns, Taiwan faces a range of external uncertainties that could impact the safety and prosperity of its people and reverberate in its politics. Here are a few key questions that could spill over into Taiwan in the year ahead. WILL THE AI BUBBLE POP? The global AI boom supported Taiwan’s significant economic expansion in 2025. Taiwan’s economy grew over 7 percent and set records for exports, imports, and trade surplus. There is a brewing debate among investors about whether the AI boom will carry forward into 2026. Skeptics warn that AI-led global equity markets are overvalued and overleveraged

Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi on Monday announced that she would dissolve parliament on Friday. Although the snap election on Feb. 8 might appear to be a domestic affair, it would have real implications for Taiwan and regional security. Whether the Takaichi-led coalition can advance a stronger security policy lies in not just gaining enough seats in parliament to pass legislation, but also in a public mandate to push forward reforms to upgrade the Japanese military. As one of Taiwan’s closest neighbors, a boost in Japan’s defense capabilities would serve as a strong deterrent to China in acting unilaterally in the

Taiwan last week finally reached a trade agreement with the US, reducing tariffs on Taiwanese goods to 15 percent, without stacking them on existing levies, from the 20 percent rate announced by US President Donald Trump’s administration in August last year. Taiwan also became the first country to secure most-favored-nation treatment for semiconductor and related suppliers under Section 232 of the US Trade Expansion Act. In return, Taiwanese chipmakers, electronics manufacturing service providers and other technology companies would invest US$250 billion in the US, while the government would provide credit guarantees of up to US$250 billion to support Taiwanese firms