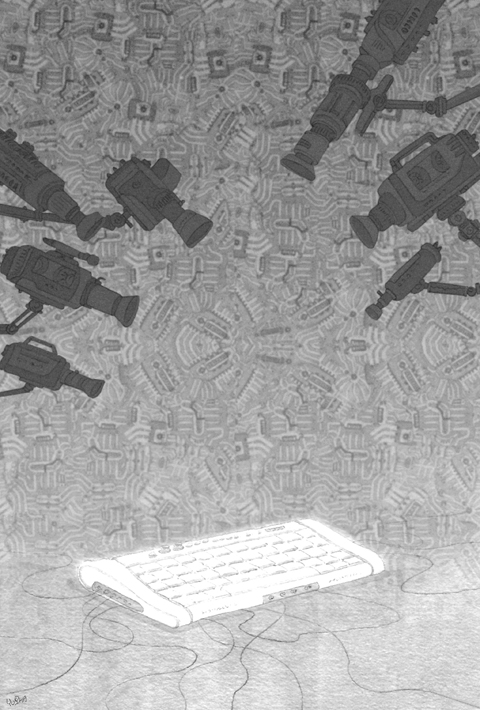

When vicious inter-ethnic violence broke out in Urumqi last year, Chinese authorities flooded the city with security forces. But next came an unexpected step: They cut off Internet access across the vast northwestern region of Xinjiang. Controlling the information flow was as crucial as controlling the streets, it seemed.

Eight months on, the net remains largely inaccessible in Xinjiang, though officials claim it will be restored. The small number of sites that were recently unblocked are heavily censored; only a severely restricted e-mail service is available.

The Internet blackout is partly an anomaly, made possible by the region’s poverty and remoteness. It is hard to imagine the authorities gambling with Shanghai or Beijing’s internationalized economies.

But it also reflects the government’s approach to the Internet: fear at the speed information or rumors can spread and people can organize. And an absolute determination to tame it. The cut-off lies at the extreme end of a spectrum of controls that experts say constitute the world’s most sophisticated and extensive censorship system — and one that is growing.

Google’s decision to shut its China search service has highlighted a crackdown that has closed thousands of domestic Web sites over the last year and blocked many hosted outside. Casualties included Yeeyan, a community translation Web site that was running a collaborative experiment with the Guardian, publishing stories in Chinese. Though it was later allowed to reopen, it no longer translates foreign news media. Other measures have included attempts to introduce real name registration and install controls on individual devices via the controversial Green Dam software — though the latter has been seen off by users, at least for now.

“A lot of people are very optimistic that the Web will bring us ‘glasnost for China’, but the determination to control it is stronger than ever,” said David Bandurski of the China Media Project at the University of Hong Kong.

Few, even those who deal with it regularly, can explain exactly how the censorship system works.

Chinese officials say most countries control the Internet and that Beijing does so according to law. The state proscribes up to 11 kinds of content, which range from spreading obscenity to “disrupting national policies on religion, propagating evil cults and feudal superstitions.”

The difference is not only that China outlaws far more content than other countries, but it does not state clearly what is off limits, why, and who made the decision.

“The special nature of Chinese censorship is that it has no transparency and is very random,” said Wen Yunchao (溫雲超), a Guangzhou-based blogger better known as Beifeng (北風, North Wind).

“When my blog has been closed or deleted or blocked, I have had no notice. After I find out there is no way to petition for its return. No netizens know which department made the decision; no one knows how the system works. We only see the results,” he said.

The first element is the so-called “Great Firewall.” Internet police bar access to services hosted overseas by blocking URLs and IP addresses and through keyword filtering. Although many Internet users find ways to scale the firewall most either do not know how or cannot be bothered.

But the second element is just as crucial: Domestic censorship. And here the authorities do not rely on controlling companies — but on making sure that they control themselves.

In evidence to a US House of Representatives hearing this month, Rebecca MacKinnon, a fellow at Princeton’s Center for Information Technology Policy, wrote: “Much of the censorship and surveillance work in China is delegated and outsourced to the private sector — who, if they fail to censor and monitor to the government’s satisfaction, will lose their business licence.”

Punishments can also include fines — or having sites closed, without warning. The decentralization of censorship means it is highly uneven. The transparency of filtering, content censored and methods used all vary. When MacKinnon tried to post 108 pieces of content on 15 different blog hosts, the most vigilant censored 60 posts; the least, only one.

At least one journalist, Shi Tao (師濤), is in jail for disclosing a propaganda directive. It is unsurprising that so few people want to discuss the system. But conversations with bloggers, industry sources and experts allow one to build up a portrait of it.

Most sites depend on both mechanized and human observation. Filtering software rejects posts outright or flags them up for further attention, but humans are essential to catch veiled references and check photographs. Sources suggest a huge portal — such as Sina, which runs not only news, but a microblog service and discussion forums — could employ anywhere between 20 and 100 censors.

These people take orders from a complex apparatus that briefs them about what is permitted, orders changes or deletions to content, and punishes them.

At the top are the Chinese Communist Party’s propaganda office and the information office of the State Council, China’s Cabinet. These deal with the biggest issues and set out a general approach; and they are replicated through the levels of the bureaucracy.

They have their own monitors who usually work as a single, city-level team. They focus on news-related Web sites, though this may include blog platforms. They shape content as well as removing it.

Separately, there are Internet police, dealing with security and crime-related issues — though in China these are interpreted very broadly. Usually they order deletion or site closures. It is thought they focus on social Web sites, such as bulletin boards; and their work veers towards information that may have offline repercussions for police and investigations.

These three groups form the bulk of the official censors. Within their ranks dedicated teams watch major sites. Like the firms’ own monitors, they work round the clock. Others will run searches on keywords, or check out tips from the public.

But there are numerous other entities overseeing parts of the Internet — the broadcasting administration deals with videos, for instance. Although they coordinate and cooperate, responsibilities overlap and turf wars can result.

Additionally, each government department or agency keeps an eye on its own patch. Usually these bodies will act via police or information and propaganda officials; sometimes, they call Web sites directly. It is not clear if they have the right to order deletion of content, but companies usually comply.

“Literally, pretty much every government office will try to contact you if they have your number,” an industry figure said.

Orders arrive in different ways. Censors may tell a site to delete content, or tell an ISP to pull the plug. Sometimes a data center informs a company they have been told to shut a site; sometimes they act without warning or explanation.

Authorities will call major players to meetings to brief them; otherwise, they will ring up, send a text message or use online chat services. Smaller sites often rely on word of mouth. But companies usually maintain logs and occasionally these leak, offering a glimpse into the complex and baffling decisions of the censors.

One, said to have belonged to Chinese search giant Baidu, included banned sites, off-limits topics and sensitive words or phrases including AIDS, reactionary and even Communist Party; not problematic in themselves, but in certain combinations.

The censors’ decisions can be baffling — allowing tales of official abuse to remain while innocuous subjects are erased; one list translated by the New York Times last week included an order to delete references to a rare flower.

“The rest of us have to guess their likes and dislikes,” one of those struggling to keep up said.

Officials do not only prohibit content, they dictate how stories are reported; or if reader comments should be allowed; or set a ratio of “positive” stories.

“In the past it was about deleting. Now they do much more — saying what we should put on the headlines,” an industry source said.

“They don’t haul in everyone,” Phelim Kine said, Asia researcher at Human Rights Watch.

However, “discussion of the government’s monopoly on power; the need to examine 1989; calls for open elections — those are red flag issues and can get people a knock on the door,” he said.

Then there are topics and discussions acceptable today but perhaps not tomorrow. A summons to an intimidatory chat with police; detention; or jail could be the result. Amnesty International calculated last year about 30 journalists and 50 others were in prison “for posting their views.”

“Because people don’t know what they are not allowed to say, they kind of guess and take down or stop saying whatever might possibly not be permissible,” Wen, aka Beifeng, said.

The system’s effectiveness can be judged by what it has not done and does not need to do.

Li Yonggang (李永剛), a professor at Nanjing University, wrote: “In fact, the Great Firewall is rooted in our hearts.”

Elbridge Colby, America’s Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, is the most influential voice on defense strategy in the Second Trump Administration. For insight into his thinking, one could do no better than read his thoughts on the defense of Taiwan which he gathered in a book he wrote in 2021. The Strategy of Denial, is his contemplation of China’s rising hegemony in Asia and on how to deter China from invading Taiwan. Allowing China to absorb Taiwan, he wrote, would open the entire Indo-Pacific region to Chinese preeminence and result in a power transition that would place America’s prosperity

When Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) caucus whip Ker Chien-ming (柯建銘) first suggested a mass recall of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislators, the Taipei Times called the idea “not only absurd, but also deeply undemocratic” (“Lai’s speech and legislative chaos,” Jan. 6, page 8). In a subsequent editorial (“Recall chaos plays into KMT hands,” Jan. 9, page 8), the paper wrote that his suggestion was not a solution, and that if it failed, it would exacerbate the enmity between the parties and lead to a cascade of revenge recalls. The danger came from having the DPP orchestrate a mass recall. As it transpired,

A few weeks ago in Kaohsiung, tech mogul turned political pundit Robert Tsao (曹興誠) joined Western Washington University professor Chen Shih-fen (陳時奮) for a public forum in support of Taiwan’s recall campaign. Kaohsiung, already the most Taiwanese independence-minded city in Taiwan, was not in need of a recall. So Chen took a different approach: He made the case that unification with China would be too expensive to work. The argument was unusual. Most of the time, we hear that Taiwan should remain free out of respect for democracy and self-determination, but cost? That is not part of the usual script, and

All 24 Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers and suspended Hsinchu Mayor Ann Kao (高虹安), formerly of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), survived recall elections against them on Saturday, in a massive loss to the unprecedented mass recall movement, as well as to the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) that backed it. The outcome has surprised many, as most analysts expected that at least a few legislators would be ousted. Over the past few months, dedicated and passionate civic groups gathered more than 1 million signatures to recall KMT lawmakers, an extraordinary achievement that many believed would be enough to remove at