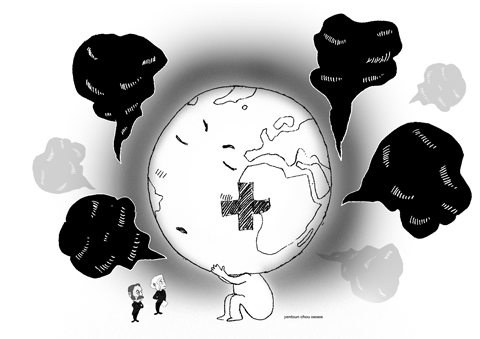

Our current approach to solving global warming will not work. It is flawed economically, because carbon taxes will cost a fortune and do little, and it is flawed politically, because negotiations to reduce carbon dioxide emissions will become ever more fraught and divisive. And even if you disagree on both counts, the current approach is also flawed technologically.

Many countries are now setting ambitious carbon-cutting goals ahead of global negotiations in Copenhagen this December to replace the Kyoto Protocol. Let us imagine that the world ultimately agrees on an ambitious target. Say we decide to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by three-quarters by 2100 while maintaining reasonable growth. Herein lies the technological problem: to meet this goal, non-carbon-based sources of energy would have to be an astounding 2.5 times greater in 2100 than the level of total global energy consumption was in 2000.

These figures were calculated by economists Chris Green and Isabel Galiana of McGill University. Their research shows that confronting global warming effectively requires nothing short of a technological revolution. We are not taking this challenge seriously. If we continue on our current path, technological development will be nowhere near significant enough to make non-carbon-based energy sources competitive with fossil fuels on price and effectiveness.

In Copenhagen this December, the focus will be on how much carbon to cut, rather than on how to do so. Little or no consideration will be given to whether the means of cutting emissions are sufficient to achieve the goals.

MISPLACED FAITH

Politicians will base their decisions on global warming models that simply assume that technological breakthroughs will happen by themselves. This faith is sadly — and dangerously — misplaced.

Green and Galiana examine the state of non-carbon-based energy today — nuclear, wind, solar, geothermal, etc — and find that, taken together, alternative energy sources would get us less than halfway toward a path of stable carbon emissions by 2050, and only a tiny fraction of the way toward stabilization by 2100. We need many, many times more non-carbon-based energy than is currently produced.

Yet the needed technology will not be ready in terms of scalability or stability. In many cases, there is still a need for the most basic research and development. We are not even close to getting this revolution started.

Current technology is so inefficient that — to take just one example — if we were serious about wind power, we would have to blanket most countries with wind turbines to generate enough energy for everybody, and we would still have the massive problem of storage: we don’t know what to do when the wind doesn’t blow.

Policymakers should abandon fraught carbon-reduction negotiations, and instead make agreements to invest in research and development to get this technology to the level where it needs to be. Not only would this have a much greater chance of actually addressing climate change, but it would also have a much greater chance of political success. The biggest emitters of the 21st century, including India and China, are unwilling to sign up to tough, costly emission targets. They would be much more likely to embrace a cheaper, smarter, and more beneficial path of innovation.

WRONG QUESTION

Today’s politicians focus narrowly on how high a carbon tax should be to stop people from using fossil fuels. That is the wrong question. The market alone is an ineffective way to stimulate research and development into uncertain technology, and a high carbon tax will simply hurt growth if alternatives are not ready. In other words, we will all be worse off.

Green and Galiana propose limiting carbon pricing initially to a low tax (say, US$5 a tonne) to finance energy research and development. Over time, they argue, the tax should be allowed to rise slowly to encourage the deployment of effective, affordable technology alternatives.

Investing about US$100 billion annually in non-carbon-based energy research would mean that we could essentially fix climate change on the century scale. Green and Galiana calculate the benefits — from reduced warming and greater prosperity — and conservatively conclude that for every dollar spent this approach would avoid about US$11 of climate damage. Compare this to other analyses showing that strong and immediate carbon cuts would be expensive, yet achieve as little as US$0.02 of avoided climate damage.

If we continue implementing policies to reduce emissions in the short term without any focus on developing the technology to achieve this, there is only one possible outcome: virtually no climate impact, but a significant dent in global economic growth, with more people in poverty, and the planet in a worse place than it could be.

Bjorn Lomborg is director of the Copenhagen Consensus Center and adjunct professor at Copenhagen Business School.

COPYRIGHT: PROJECT SYNDICATE

In the US’ National Security Strategy (NSS) report released last month, US President Donald Trump offered his interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine. The “Trump Corollary,” presented on page 15, is a distinctly aggressive rebranding of the more than 200-year-old foreign policy position. Beyond reasserting the sovereignty of the western hemisphere against foreign intervention, the document centers on energy and strategic assets, and attempts to redraw the map of the geopolitical landscape more broadly. It is clear that Trump no longer sees the western hemisphere as a peaceful backyard, but rather as the frontier of a new Cold War. In particular,

When it became clear that the world was entering a new era with a radical change in the US’ global stance in US President Donald Trump’s second term, many in Taiwan were concerned about what this meant for the nation’s defense against China. Instability and disruption are dangerous. Chaos introduces unknowns. There was a sense that the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) might have a point with its tendency not to trust the US. The world order is certainly changing, but concerns about the implications for Taiwan of this disruption left many blind to how the same forces might also weaken

As the new year dawns, Taiwan faces a range of external uncertainties that could impact the safety and prosperity of its people and reverberate in its politics. Here are a few key questions that could spill over into Taiwan in the year ahead. WILL THE AI BUBBLE POP? The global AI boom supported Taiwan’s significant economic expansion in 2025. Taiwan’s economy grew over 7 percent and set records for exports, imports, and trade surplus. There is a brewing debate among investors about whether the AI boom will carry forward into 2026. Skeptics warn that AI-led global equity markets are overvalued and overleveraged

As the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) races toward its 2027 modernization goals, most analysts fixate on ship counts, missile ranges and artificial intelligence. Those metrics matter — but they obscure a deeper vulnerability. The true future of the PLA, and by extension Taiwan’s security, might hinge less on hardware than on whether the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) can preserve ideological loyalty inside its own armed forces. Iran’s 1979 revolution demonstrated how even a technologically advanced military can collapse when the social environment surrounding it shifts. That lesson has renewed relevance as fresh unrest shakes Iran today — and it should