The last team Inspector Liz Owsley of London’s Metropolitan Police (the Met) worked on, not so long ago, happened to have just one woman. All the rest were young male police constables. There was a moment, she relates, when a bit of a situation was starting to kick off with a bunch of yobs in a courtyard. A constable was getting overly verbal with one of the lads, trading insults — a real slanging match.

“So the woman officer just turned to him and said, quite gently: ‘You’re not helping,’” Owsley recalls. “It was only a small thing, tiny really, but it was classic. Women police will always want to resolve a situation with the least possible upset. Their question is always, can we do this without confrontation? Is it possible without conflict? There just isn’t that same kind of macho aggressiveness you can get from the men. We’re better communicators.”

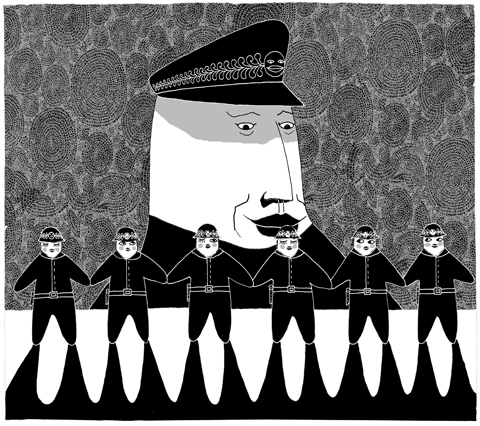

After the public outrage and official brickbats heaped on the Met’s handling of the G20 protests in London in April, during which a newspaper vendor, Ian Tomlinson, died after being hit by a police officer, news this week that both senior officers controlling tactics at next week’s Climate Camp will be women has been broadly welcomed as evidence that the force may be trying to adopt a less confrontational approach to policing demonstrations.

Superintendent Julia Pendry — who once took the Met to an employment tribunal before settling her sexual discrimination claim out of court — has been named “silver” commander for the operation, and was quoted as saying she selected her deputy, Inspector Jane Connors, because she was “reasonable, sensible and able to communicate.”

Perhaps the most noted American researcher into gender differences in policing, Joseph Balkin, observed that “policemen tend to see police work as involving control through authority, while policewomen see it as public service.”

In some respects at least, he concluded, “women are better suited for police work than men.”

Can the Climate Camp protesters really expect a different experience, however, to the unpleasant, even brutal one many of them encountered in London’s City earlier this year, simply because the officers in charge are women?

Certainly their management style is likely to be different, believes Jennifer Brown, a professor of forensic psychology at the University of Surrey in southern England who has spent the best part of 20 years researching gender issues in policing.

“The police service has been thinking a lot about leadership styles, about the difference between transactional leadership — ‘This is what I think we should do’ — and transformational leadership, which is more consultative, ‘negotiative,’” Brown said. “As a generality, the way in which women police approach leadership ... is more likely to be: ‘Let’s sit down, let’s think about this together, let’s hear what everyone has to say.’”

That would seem to be borne out by at least one study published in a leading US police journal, which concluded that female police executives tend to be “more flexible, emotionally independent, self-assertive, self-confident, proactive and creative than their male counterparts.”

Male police executives, on the other hand, were “more authoritarian and prejudiced.”

Several promising preliminary meetings have reportedly already been held between the Met and the event’s organizers, who have also been assured that the more controversial policing methods used at last year’s Climate Camp at Kingsnorth power station in Kent, southeast England — placing a “ring of steel” around the camp, for example, and depriving protesters of sleep by playing loud music through the night — will not be repeated.

It will be what transpires on the ground, though, that will determine whether the police approach really has changed. The whole exercise, may be simply one big public relations exercise.

“I wonder whether the young woman who may have suffered a miscarriage after the beating she received on Bishopsgate [in the City] would agree about the positive virtues of women police officers?” said Kevin Blowe, a the charity worker, campaigner and blogger who was on the G20 protest.

He is clearly skeptical of any change of heart — or tactics — by the Met.

As Blowe points out, the woman said that “one of the most traumatic visual moments for me was that a female police officer in front of me had blood spattered on the outside of her visor. I was so lost in fear and shock by this point that I said: ‘Do you know you have blood on your visor?’ That really upset her and I really got laid into and I got knocked on to the floor and all the people trying to help me ... were also hit.”

There is now, however, based largely on extensive US research, a mounting body of evidence indicating that women officers do indeed behave differently on the ground to their male colleagues, especially in potentially difficult situations.

“Women police officers rely on a style of policing that uses less physical force, are better at defusing and de-escalating potentially violent confrontations, and are less likely to become involved in problems with use of excessive force,” wrote, unambiguously, the authors of one report. “In addition, women officers tend to possess better communications skills than their male counterparts and are better able to facilitate the co-operation and trust required to implement a community policing model.”

Brown confirms that “for the most part, men are more likely to get themselves into trouble through the use of force. The number of complaints against men is proportionately higher. Women are less likely to resort to batons, pepper spray or quick cuffs to get out of trouble, and more likely to use negotiative skills to talk someone down.”

Perhaps most significantly, in light of the allegations leveled at some Met officers policing the G20 protests, a study for the US National Center for Women and Policing shows big differences between men and women police in the use of excessive force. Combining data from seven major US police agencies, the researchers found that while 13 percent of big city officers were women, meaning that proportionately they should be involved in around 13 percent of all incidents, the real figures were far lower.

The authors of Men, Women and Police Excessive Force: A Tale of Two Genders conclude that the average male police officer in the US costs from 2.5 to five times more than the average woman officer in compensation payments for excessive force; is nine times more likely to have an allegation of excessive force upheld against him; and is three times more likely to be named in a public complaint over the use of excessive force.

This could, of course, be down to the fact that women police are exposed to fewer situations that might require the use of force, but the researchers also produced data from two 1990s scientific studies funded by the US National Institute of Justice showing that there was no significant difference between female and male officers when it came the use of legitimate force during “routine patrol duties” — including arrests.

In short, women officers are not necessarily reluctant to use force, but they are far less likely to use excessive force.

“Excessive use of force takes a serious toll on the individuals involved, but excessive force incidents [also] severely erode the trust between the police and the public,” said the report’s authors, who include the center’s director, Margaret Moore. “Every sustained allegation undermines the confidence the community places in their police, and limits the police’s effectiveness to fight crime and serve the public. When the community comes to mistrust the police, they withdraw the cooperation that is essential for police to perform their job.”

That argument presents a convincing case for putting many more women officers on the streets. There are others: studies in the US and elsewhere — summarized in the report Hiring and Retaining More Women: The Advantages to Law Enforcement Agencies — show that in terms of overall competence, effectiveness and productivity on patrol, there are no meaningful differences between male and female officers, and (a tough chestnut this one) that physical strength and aggression are not determining factors in either general police effectiveness, or the ability to successfully handle a dangerous situation.

Others have it that women officers are far more in tune with the aims of “community-oriented policing,” the generally accepted modern approach to policing which is based more on communication and cooperation with the public. Women police have been found to be the target of fewer insults than their male colleagues; to be less cynical and more respectful of members of the public; to have a beneficial influence on the behavior of their male colleagues and a community advantage over men in several areas, “including empathy toward others and interacting in a way which is not designed to ‘prove’ anything.”

You could almost formulate the question this way, said one female officer who asked not to be identified: “It’s not, can women make good police officers. It’s why should so many unsuitable men, with the way they respond to so many situations, the way they so often have to prove who’s biggest, be allowed to try? Any policewoman could give you a dozen examples of male colleagues getting it wrong.”

There has not been much research of this sort in the UK, where women police make up around 25 percent of the overall service — a figure that has been growing by about 1 percent a year for the past decade or so (most British research, it seems, has focused on the difficulties women police officers face in advancing their careers).

There is an acknowledgment within the service, however, said one study supervised by Brown, that it needs to “reconsider its style and priorities ... and create a model of policing that is more consultative. The model that has evolved takes on initiatives having the appearance of a more feminized style.”

The overall trend, the study’s authors said, has been “a shift toward interpersonal and communication skills away from the physical skills pre-eminent in more traditional models of policing.”

Brown’s research for the British Association of Women in Policing (BAWP) into whether members of the public had a preference for the sex of officer they would like to see deployed in certain tasks, however, threw up some unexpected results.

“Essentially, people seem to feel that if a job is perceived as requiring muscle — dealing with a football hooligan, sorting out a pub fight — then men are better,” she said. “Strength and assertiveness were seen as important. If it’s something like dealing with victims of sexual abuse, or domestic violence, they’d rather see police women involved. It’s almost as if the public are behind the actuality.”

The response to the murder of PC Sharon Beshenivsky, who was shot dead during a robbery in Bradford, northern England, in 2005 and was only the second female officer in the UK to be fatally shot, reveals “we somehow still find it more alarming to see a young woman hurt and possibly killed. There’s a feeling of, should women really be doing this, getting into these kind of situations?”

In fact, all the evidence shows “if women are involved, both parties are more likely to emerge with their heads intact.”

There remain obstacles, not so much to the recruitment but the retention of female officers, said Owsley, who has 20 years’ experience in the service and is now national coordinator of BAWP. Flexible working in particular is the bugbear.

“They just can’t get their heads round it,” Owlsey said. “There are some supervisors out there who will tell you quite plainly women shouldn’t be promoted.”

Brown — who cautions against generalizing and notes that it is perfectly possible for male police to have “a more feminine way of doing things,” and vice versa — puts it this way: “There’s still a culture that if you’re not dedicated to the job 24/7, you’re only half a copper.”

The benefits to police forces and the public of having more women officers, however, are now unarguable, Owsley said.

“The real issue is changing the culture,” she said. “Things could be changed overnight if the Association of Chief Police Officers wanted them changed.”

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has long been expansionist and contemptuous of international law. Under Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平), the CCP regime has become more despotic, coercive and punitive. As part of its strategy to annex Taiwan, Beijing has sought to erase the island democracy’s international identity by bribing countries to sever diplomatic ties with Taipei. One by one, China has peeled away Taiwan’s remaining diplomatic partners, leaving just 12 countries (mostly small developing states) and the Vatican recognizing Taiwan as a sovereign nation. Taiwan’s formal international space has shrunk dramatically. Yet even as Beijing has scored diplomatic successes, its overreach

After more than a year of review, the National Security Bureau on Monday said it has completed a sweeping declassification of political archives from the Martial Law period, transferring the full collection to the National Archives Administration under the National Development Council. The move marks another significant step in Taiwan’s long journey toward transitional justice. The newly opened files span the architecture of authoritarian control: internal security and loyalty investigations, intelligence and counterintelligence operations, exit and entry controls, overseas surveillance of Taiwan independence activists, and case materials related to sedition and rebellion charges. For academics of Taiwan’s White Terror era —

After 37 US lawmakers wrote to express concern over legislators’ stalling of critical budgets, Legislative Speaker Han Kuo-yu (韓國瑜) pledged to make the Executive Yuan’s proposed NT$1.25 trillion (US$39.7 billion) special defense budget a top priority for legislative review. On Tuesday, it was finally listed on the legislator’s plenary agenda for Friday next week. The special defense budget was proposed by President William Lai’s (賴清德) administration in November last year to enhance the nation’s defense capabilities against external threats from China. However, the legislature, dominated by the opposition Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), repeatedly blocked its review. The

In her article in Foreign Affairs, “A Perfect Storm for Taiwan in 2026?,” Yun Sun (孫韻), director of the China program at the Stimson Center in Washington, said that the US has grown indifferent to Taiwan, contending that, since it has long been the fear of US intervention — and the Chinese People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) inability to prevail against US forces — that has deterred China from using force against Taiwan, this perceived indifference from the US could lead China to conclude that a window of opportunity for a Taiwan invasion has opened this year. Most notably, she observes that