Algerian shopkeeper Abdelkrim Salouda has witnessed China’s global economic expansion first-hand and he does not like it, especially since he was in a mass brawl this month with Chinese migrant workers.

“They have offended us with their bad behavior,” said Salouda, a devout Muslim who lives in a suburb of the Algerian capital. “In the evening ... they drink beer, and play cards and they wear shorts in front of the residents.”

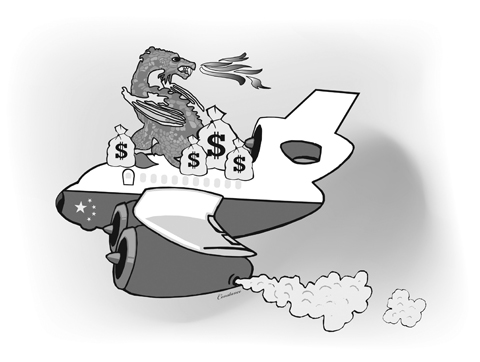

From Africa to Europe, the Middle East and the US, China’s drive to project its economic might abroad can sometimes breed fear and resentment.

The risks are likely to grow as Beijing channels more of its foreign exchange reserves, which stood at US$2.13 trillion at the end of June, into foreign investments.

From having a handful of tiny investments abroad less than two decades ago, China has grown to the world’s sixth-biggest foreign investor and overtook the US as Africa’s top trading partner last year.

That breathtaking rise has brought problems: allegations from emerging countries that China is stripping them of resources and suspicions in the developed world that obscure state interests lurk behind Chinese investments.

Where governments welcome Chinese investments for the boost they bring to their economies, a widely perceived Chinese tendency for Chinese firms to import their own workers has created tensions with job-seekers.

“It’s very new, it’s very big, it’s full of potential hazards, it’s also full of potential benefits,” said Kerry Brown, senior fellow at Britain’s Chatham House think tank.

The challenge of how to deal with such tensions will only be magnified as the global slowdown prompts Beijing to pump even more of its foreign exchange reserves overseas.

China used to be content to keep its surplus dollars in the bank or in US government debt. But the financial crisis and subsequent downturn have, in some quarters, shaken faith in the strength of the dollar and US Treasuries. With China still needing to secure access to global resources, some Chinese policy-makers are talking about redirecting billions of dollars into overseas investment instead.

The resentment felt by the Algerian shopkeeper toward his new Chinese neighbors is not universal: people in many places welcome the benefits from Chinese investment.

Those can include aid with few strings attached, capital for infrastructure that Western donors will not fund and competition that drives down prices.

Despite the clashes in Algeria’s capital this month, its government welcomes Chinese investment.

A US$9 billion minerals-for-infrastructure deal is presented by Democratic Republic of the Congo (DR Congo) President Joseph Kabila as a cornerstone of his plan to rebuild the DR Congo after years of war. China will build roads, schools and hospitals in exchange for mining rights. In Guinea’s capital, Conakry, the Chinese government is building a 50,000-seat sports stadium as a gift.

“We are very satisfied with our cooperation with China,” Republic of the Congo President Denis Sassou-Nguesso said on a visit to a hydro-electric dam being built by Chinese contractors.

“Contrary to certain assertions, it’s not just Chinese on the various construction sites, there are also numerous Congolese workers,” he said.

But in some countries, it is the sheer size of the Chinese presence that causes tension.

Russian officials estimated that last year there were 350,000 Chinese migrants living in the country’s far eastern regions, many illegally. The native population, in an area almost 10 times the size of France, is just more than 7 million.

Asked if the numbers of Chinese migrants jeopardized Moscow’s control there, a senior Russian migration official said: “There is a threat. It should not be overstated but there is a threat.”

The official did not want to be identified because of the sensitivity of the subject.

Elsewhere, the fact that the lion’s share of Chinese investments are from the state itself or state-controlled companies is the source of friction.

One of the best-known cases of thwarted Chinese expansion was when US lawmakers blocked the sale of oil company UNOCAL to China’s CNOOC Ltd in 2005.

One senator said the deal would effectively give the Chinese Communist Party control over a strategic US resource.

In Sudan, rebels accuse Beijing of supporting Khartoum in the six-year-old conflict in Darfur — and they see Chinese companies as the embodiment of that policy.

“Their only interest in Sudan is their own economic benefit,” said Al-Tahir al-Feki, a spokesman for Sudan’s rebel Justice and Equality Movement. “As soon as that benefit is gone they will disappear, leaving so many things destroyed behind them.”

Another accusation leveled at Chinese investors is that they cut corners.

Five Zambians were shot and wounded in 2005 in a riot over pay and safety standards at a Chinese-owned mine, and a year later 52 Zambians were killed in an explosion at a Chinese firm manufacturing explosives for mining.

In January, Chinese traders in Guinea closed their shops for several days for fear of reprisals after the authorities found Chinese-made fake medicines.

“A part of the population attacked the Chinese expatriates, whom they associated with the offenders. We ... had to intervene to calm the situation,” said a military source who was speaking on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak to the media.

China says its investors are forced to go into “frontier markets” because developed countries lock them out of more stable economies. As a result, they say, the risks they face are higher.

There is some truth in that argument, said Brown, a former British diplomat in Beijing and the author of The Rise of the Dragon, a book on Chinese investment.

“The underlying pattern we find is that in countries where governance is decent like Botswana or South Africa, where there’s reasonable rule of law and some kinds of infrastructure to control ... Chinese investment, then it’s not too problematic,” he said. “However, in countries where there are problems of governance, problems of environmental impact, problems of labor rights, unfortunately Chinese investment performs very poorly indeed.”

China has started to address the damage to its reputation as an overseas investor. Big firms have hired Western consultancy firms to give advice. Many are now seeking local partners, or favoring less high-profile indirect investments.

There are signs too that the Chinese government is doing more to win over the trust of local communities.

In Algeria, the Chinese embassy said it had advised its nationals to respect the country’s traditions. In Zambia, poor communities have received Chinese donations that include footballs and boreholes for drinking water.

But much of the responsibility will still rest with investment recipients to set out clear rules on how they manage the growing flows of cash.

“My hunch is that foreign governments have got to make decisions about where they want the money to go and where they say no,” Kerry said.

In the US’ National Security Strategy (NSS) report released last month, US President Donald Trump offered his interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine. The “Trump Corollary,” presented on page 15, is a distinctly aggressive rebranding of the more than 200-year-old foreign policy position. Beyond reasserting the sovereignty of the western hemisphere against foreign intervention, the document centers on energy and strategic assets, and attempts to redraw the map of the geopolitical landscape more broadly. It is clear that Trump no longer sees the western hemisphere as a peaceful backyard, but rather as the frontier of a new Cold War. In particular,

When it became clear that the world was entering a new era with a radical change in the US’ global stance in US President Donald Trump’s second term, many in Taiwan were concerned about what this meant for the nation’s defense against China. Instability and disruption are dangerous. Chaos introduces unknowns. There was a sense that the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) might have a point with its tendency not to trust the US. The world order is certainly changing, but concerns about the implications for Taiwan of this disruption left many blind to how the same forces might also weaken

As the new year dawns, Taiwan faces a range of external uncertainties that could impact the safety and prosperity of its people and reverberate in its politics. Here are a few key questions that could spill over into Taiwan in the year ahead. WILL THE AI BUBBLE POP? The global AI boom supported Taiwan’s significant economic expansion in 2025. Taiwan’s economy grew over 7 percent and set records for exports, imports, and trade surplus. There is a brewing debate among investors about whether the AI boom will carry forward into 2026. Skeptics warn that AI-led global equity markets are overvalued and overleveraged

Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi on Monday announced that she would dissolve parliament on Friday. Although the snap election on Feb. 8 might appear to be a domestic affair, it would have real implications for Taiwan and regional security. Whether the Takaichi-led coalition can advance a stronger security policy lies in not just gaining enough seats in parliament to pass legislation, but also in a public mandate to push forward reforms to upgrade the Japanese military. As one of Taiwan’s closest neighbors, a boost in Japan’s defense capabilities would serve as a strong deterrent to China in acting unilaterally in the