The continuous presentation of scary stories about global warming in the popular media makes us unnecessarily frightened. Even worse, it terrifies our kids.

Former US vice president Al Gore famously depicted how a sea-level rise of 6m would almost completely flood Florida, New York, Holland, Bangladesh and Shanghai, even though the UN estimates that sea levels will rise 20 times less than that, and do no such thing.

When confronted with these exaggerations, some of us say that they are for a good cause and surely there is no harm done if the result is that we focus even more on tackling climate change. A similar argument was used when former US president George W. Bush’s administration overstated the terror threat from Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein.

But this argument is astonishingly wrong. Such exaggerations do plenty of harm. Worrying excessively about global warming means that we worry less about other things, where we could do so much more good. We focus, for example, on global warming’s impact on malaria — which will be to put slightly more people at risk in 100 years — instead of tackling the half-billion people suffering from malaria today with prevention and treatment policies that are much cheaper and dramatically more effective than carbon reduction would be.

Exaggeration also wears out the public’s willingness to tackle global warming. If the planet is doomed, people wonder, why do anything? A record 54 percent of US voters now believe the news media make global warming appear worse than it really is. A majority of people now believe — incorrectly — that global warming is not even caused by humans. In the UK, 40 percent believe that global warming is exaggerated and 60 percent doubt that it is man-made.

But the worst cost of exaggeration, I believe, is the unnecessary alarm that it causes — particularly among children. Recently, I discussed climate change with a group of Danish teenagers. One of them worried that global warming would cause the planet to “explode” — and all the others had similar fears.

In the US, the ABC TV network recently reported that psychologists were starting to see more neuroses in people anxious about climate change. An article in the Washington Post cited nine-year-old Alyssa, who cries about the possibility of mass animal extinctions from global warming.

In her words: “I don’t like global warming because it kills animals, and I like animals.”

From a child who is yet to lose all her baby teeth: “I worry about [global warming] because I don’t want to die.”

The newspaper also reported that parents were searching for “productive” outlets for their eight-year-olds’ obsessions with dying polar bears. They might be better off educating them and letting them know that, contrary to common belief, the global polar bear population has doubled and perhaps even quadrupled over the past half-century, to about 22,000. Despite diminishing — and eventually disappearing — summer Arctic ice, polar bears will not become extinct. After all, in the first part of the current interglacial period, glaciers were almost entirely absent in the northern hemisphere, and the Arctic was probably ice-free for 1,000 years, yet polar bears are still with us.

Another nine-year old showed the Washington Post his drawing of a global warming timeline.

“That’s the Earth now,” Alex says, pointing to a dark shape at the bottom. “And then it’s just starting to fade away.”

Looking up to make sure his mother was following along, he tapped the end of the drawing: “In 20 years, there’s no oxygen.”

Then, to dramatize the point, he collapsed, “dead,” to the floor.

And these are not just two freak stories. In a new survey of 500 US pre-teens, it was found that one in three children between the ages of six and 11 feared that the Earth would not exist when they reach adulthood because of global warming and other environmental threats. An unbelievable one-third of our children believe that they don’t have a future because of scary global warming stories.

We see the same pattern in the UK, where a survey showed that half of young children between the ages of seven and 11 were anxious about the effects of global warming, often losing sleep because of their concern. This is grotesquely harmful.

And let us be honest. This scare was intended. Children believe that global warming will destroy the planet before they grow up because adults are telling them that .

When every prediction about global warming is scarier than the last one, and the scariest predictions — often not backed up by peer-reviewed science — get the most airtime, it is little wonder that children are worried.

Nowhere is this deliberate fearmongering more obvious than in Gore’s Inconvenient Truth, a film that was marketed as “by far the most terrifying film you will ever see.”

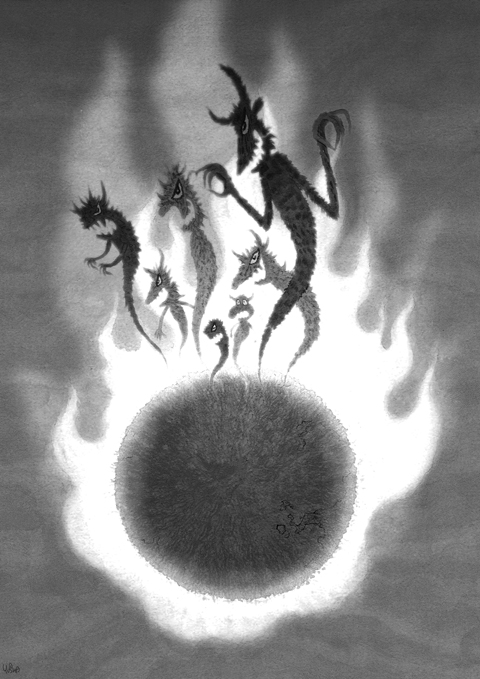

Take a look at the trailer for this movie on YouTube. Notice the imagery of chilling, larger-than-life forces evaporating our future. The commentary tells us that this film has “shocked audiences everywhere,” and that “nothing is scarier” than what Gore is about to tell us. Notice how the trailer even includes a nuclear explosion.

The current debate about global warming is clearly harmful. I believe that it is time we demanded that the media stop scaring us and our kids silly. We deserve a more reasoned, more constructive and less frightening dialogue.

Bjorn Lomborg, the director of the Copenhagen Consensus Center, is an adjunct professor at the Copenhagen Business School and author of The Skeptical Environmentalist and Cool It: The Skeptical Environmentalist’s Guide to Global Warming.

COPYRIGHT: PROJECT SYNDICATE

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has long been expansionist and contemptuous of international law. Under Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平), the CCP regime has become more despotic, coercive and punitive. As part of its strategy to annex Taiwan, Beijing has sought to erase the island democracy’s international identity by bribing countries to sever diplomatic ties with Taipei. One by one, China has peeled away Taiwan’s remaining diplomatic partners, leaving just 12 countries (mostly small developing states) and the Vatican recognizing Taiwan as a sovereign nation. Taiwan’s formal international space has shrunk dramatically. Yet even as Beijing has scored diplomatic successes, its overreach

After 37 US lawmakers wrote to express concern over legislators’ stalling of critical budgets, Legislative Speaker Han Kuo-yu (韓國瑜) pledged to make the Executive Yuan’s proposed NT$1.25 trillion (US$39.7 billion) special defense budget a top priority for legislative review. On Tuesday, it was finally listed on the legislator’s plenary agenda for Friday next week. The special defense budget was proposed by President William Lai’s (賴清德) administration in November last year to enhance the nation’s defense capabilities against external threats from China. However, the legislature, dominated by the opposition Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), repeatedly blocked its review. The

In her article in Foreign Affairs, “A Perfect Storm for Taiwan in 2026?,” Yun Sun (孫韻), director of the China program at the Stimson Center in Washington, said that the US has grown indifferent to Taiwan, contending that, since it has long been the fear of US intervention — and the Chinese People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) inability to prevail against US forces — that has deterred China from using force against Taiwan, this perceived indifference from the US could lead China to conclude that a window of opportunity for a Taiwan invasion has opened this year. Most notably, she observes that

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) said on Monday that it would be announcing its mayoral nominees for New Taipei City, Yilan County and Chiayi City on March 11, after which it would begin talks with the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) to field joint opposition candidates. The KMT would likely support Deputy Taipei Mayor Lee Shu-chuan (李四川) as its candidate for New Taipei City. The TPP is fielding its chairman, Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌), for New Taipei City mayor, after Huang had officially announced his candidacy in December last year. Speaking in a radio program, Huang was asked whether he would join Lee’s