In August, Russian troops moved into Georgia. Observers dispute who fired first, but there was a little noticed dimension of the conflict that will have major repercussions for the future.

Computer hackers attacked Georgian government Web sites in the weeks preceding the outbreak of armed conflict. The Russia-Georgia conflict represents the first significant cyber attacks accompanying armed conflict. Welcome to the 21st century.

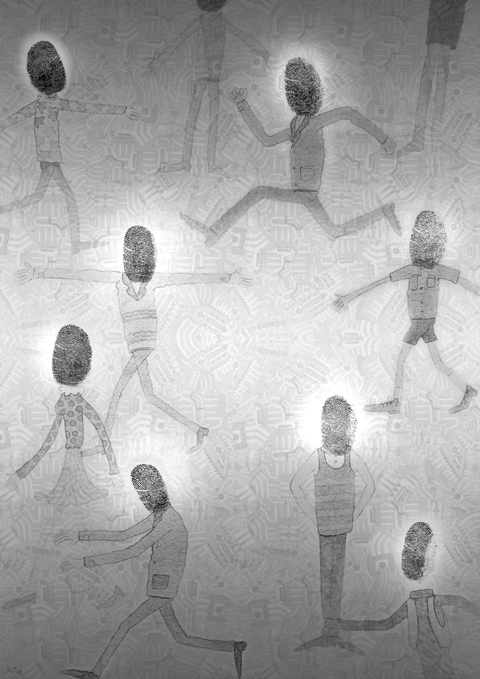

Cyber threats and potential cyber warfare illustrate the increased vulnerabilities and loss of control in modern societies. Governments have mainly been concerned about hacker attacks on their own bureaucracy’s information technology infrastructure, but there are social vulnerabilities well beyond government computers.

In an open letter to the US president in September last year, US professionals in cyber defense warned that “the critical infrastructure of the United States, including electrical power, finance, telecommunications, health care, transportation, water, defense, and the Internet, is highly vulnerable to cyber attack. Fast and resolute mitigating action is needed to avoid national disaster.”

In the murky world of the Internet, attackers are difficult to identify.

In today’s interconnected world, an unidentified cyber attack on non-governmental infrastructure might be severely damaging. For example, some experts believe that a nation’s electric power grid may be particularly susceptible. The control systems that electric power companies use are thought vulnerable to attack, which could shut down cities and regions for days or weeks. Cyber attacks may also interfere with financial markets and cause immense economic loss by closing down commercial Web sites.

Some scenarios, including an “electronic Pearl Harbor,” sound alarmist, but they illustrate the diffusion of power from central governments to individuals. In 1941, the powerful Japanese navy used many resources to create damage thousands of miles away. Today, an individual hacker using malicious software can cause chaos in far-away places at little cost to himself.

Moreover, the information revolution enables individuals to perpetrate sabotage with unprecedented speed and scope. The so-called “love bug virus,” launched in the Phillipines in 2000, is estimated to have cost billions of dollars in damage. Terrorists, too, can exploit new vulnerabilities in cyberspace to engage in asymmetrical warfare.

In 1998, when the US complained about seven Moscow Internet addresses involved in the theft of Pentagon and NASA secrets, the Russian government replied that phone numbers from which the attacks originated were inoperative. The US had no way of knowing whether the Russian government had been involved.

More recently, last year, China’s government was accused of sponsoring thousands of hacking incidents against German federal government computers and defense and private-sector computer systems in the US. But it was difficult to prove the source of the attack, and the Pentagon had to shut down some of its computer systems.

When Estonia’s government moved a World War II statue commemorating Soviet war dead last year, hackers retaliated with a costly denial-of-service attack that closed down Estonia’s access to the Internet. There was no way to prove whether the Russian government, a spontaneous nationalist response, or both aided this transnational attack.

In January, US President George W. Bush signed two presidential directives that called for establishing a comprehensive cyber-security plan, and his budget for next year requested US$6 billion to develop a system to protect national cyber security.

President-elect Barack Obama is likely to follow suit. In his campaign, Obama called for tough new standards for cyber security and physical resilience of critical infrastructure, and promised to appoint a national cyber adviser who will report directly to him and be responsible for developing policy and coordinating federal agency efforts.

That job will not be easy, because much of the relevant infrastructure is not under direct government control. Just recently, US Deputy Director of National Intelligence Donald Kerr warned that “major losses of information and value for our government programs typically aren’t from spies ... In fact, one of the great concerns I have is that so much of the new capabilities that we’re all going to depend on aren’t any longer developed in government labs under government contract.”

Kerr described what he called “supply chain attacks” in which hackers not only steal proprietary information, but go further and insert erroneous data and programs in communications hardware and software — Trojan horses that can be used to bring down systems. All governments will find themselves exposed to a new type of threat that will be difficult to counter.

Governments can hope to deter cyber attacks just as they deter nuclear or other armed attacks. But deterrence requires a credible threat of response against an attacker. And that becomes much more difficult in a world where governments find it hard to tell where cyber attacks come from, whether from a hostile state or a group of criminals masking as a foreign government.

While an international legal code that defines cyber attacks more clearly, together with cooperation on preventive measures, can help, such arms-control solutions are not likely to be sufficient. Nor will defensive measures like constructing electronic firewalls and creating redundancies in sensitive systems.

Given the enormous uncertainties involved, the new cyber dimensions of security must be high on every government’s agenda.

Joseph Nye is a professor at Harvard University and an author.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

When it became clear that the world was entering a new era with a radical change in the US’ global stance in US President Donald Trump’s second term, many in Taiwan were concerned about what this meant for the nation’s defense against China. Instability and disruption are dangerous. Chaos introduces unknowns. There was a sense that the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) might have a point with its tendency not to trust the US. The world order is certainly changing, but concerns about the implications for Taiwan of this disruption left many blind to how the same forces might also weaken

As the new year dawns, Taiwan faces a range of external uncertainties that could impact the safety and prosperity of its people and reverberate in its politics. Here are a few key questions that could spill over into Taiwan in the year ahead. WILL THE AI BUBBLE POP? The global AI boom supported Taiwan’s significant economic expansion in 2025. Taiwan’s economy grew over 7 percent and set records for exports, imports, and trade surplus. There is a brewing debate among investors about whether the AI boom will carry forward into 2026. Skeptics warn that AI-led global equity markets are overvalued and overleveraged

Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi on Monday announced that she would dissolve parliament on Friday. Although the snap election on Feb. 8 might appear to be a domestic affair, it would have real implications for Taiwan and regional security. Whether the Takaichi-led coalition can advance a stronger security policy lies in not just gaining enough seats in parliament to pass legislation, but also in a public mandate to push forward reforms to upgrade the Japanese military. As one of Taiwan’s closest neighbors, a boost in Japan’s defense capabilities would serve as a strong deterrent to China in acting unilaterally in the

Taiwan last week finally reached a trade agreement with the US, reducing tariffs on Taiwanese goods to 15 percent, without stacking them on existing levies, from the 20 percent rate announced by US President Donald Trump’s administration in August last year. Taiwan also became the first country to secure most-favored-nation treatment for semiconductor and related suppliers under Section 232 of the US Trade Expansion Act. In return, Taiwanese chipmakers, electronics manufacturing service providers and other technology companies would invest US$250 billion in the US, while the government would provide credit guarantees of up to US$250 billion to support Taiwanese firms