It’s been almost 50 years since the Tibetan god-king fled across the Himalayas and created his government-in-exile. Decades later, the Dalai Lama and his followers are still in Dharmsala.

And the struggle for Tibet? That, they increasingly say in the hilly, northern Indian town, has been futile.

“We have failed to bring any positive change inside Tibet,” said Samdhong Rinpoche, prime minister of the government-in-exile. “The majority of Tibetans are increasingly frustrated and want more forceful change.”

Now, nearly everything is on the table for discussion. Starting today, exiled Tibetans from around the world will gather in Dharamsala, called together by the Dalai Lama for a six-day meeting that could end years of carefully moderated policies toward Beijing.

In a town of often-feuding exiles, many now have at least one thing to agree upon: Their movement has reached a crossroad. The Dalai Lama is growing old, a young generation of activists want tough talk toward China and Beijing is moving thousands of ethnic Han Chinese into Tibet.

“In 10 or 15 years, when we look back at this, we’re hopeful that we’ll see this as a historic conference,” said Tsewang Rigzin, president of the Tibetan Youth Congress, one of the more militant activist groups. “We know that we have to be rational and reasonable, but we also need to change the political stand of the Tibetan people.”

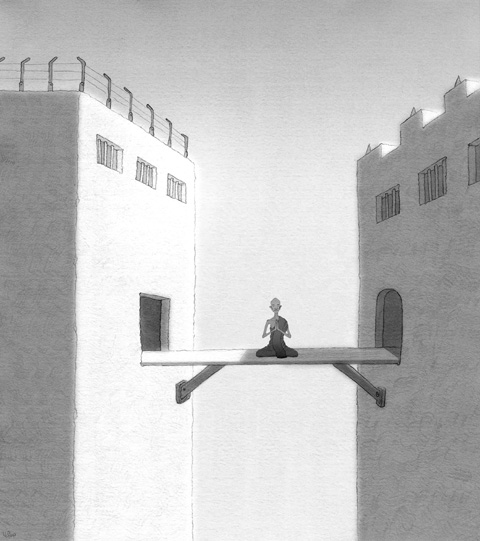

For 20 years, the exile movement has been guided by the Dalai Lama’s “middle way,” which rejects demands for outright independence but calls for limited autonomy for Tibet. Until very recently, the Dalai Lama had insisted on conciliation, repeatedly telling Beijing that progress for Tibet could come only through talks, and insisting he did not want independence.

Conciliatory talk, though, brought little but disdain from China.

Instead, Beijing derides the Dalai Lama as a “splittist,” saying he really wants a Tibetan nation. For years, talks between Beijing and the Dalai Lama’s envoys have ended in stalemate.

Last month, the man who turned patience into an art form appeared to finally grow impatient.

The Dalai Lama said in a speech that after years of pursuing the middle way “there hasn’t been any positive response.”

“As far as I’m concerned, I have given up,” he said.

From those statements came his call for the special exile conference. Many specifics remain vague, but any issues can be discussed (though policy changes would require approval by the government-in-exile). The Dalai Lama now remains silent, worried any statements would be seen as support for a particular policy.

So what sort of agendas could emerge from the conference?

The days of CIA-backed Tibetan military units ended decades ago, and even the most hard-line exiles see no hope in fighting China’s army.

Today, the clearest divide is between those favoring Tibetan autonomy and those favoring independence. But there are also endless sub-permutations, with various factions urging more protests, angrier protests, boycotts, more pressure on Western nations and, among a small group, a push for sabotage of China’s infrastructure.

With China heightening its rhetoric — last Monday, Beijing officials accused the Dalai Lama’s envoys of trickery — the exile debate has also become sharper.

“The tough line taken by China is increasing divisions among the exiles and uncertainty about what it should do,” said Robbie Barnett, an expert on modern Tibet at Columbia University.

In many ways, these debates can seem pointless. China has 1.3 billion people and the world’s largest army. The Tibetans number perhaps 6 million and are led by a devout pacifist who hasn’t been home since fleeing amid a failed uprising against Chinese rule in 1959.

But the discussions are taken deadly seriously in Dharamsala, where movement leaders hope for a time when changes in China will lead to meaningful change in Tibet.

Certainly, this is a time of turmoil in the Tibetan exile movement. Bloody anti-government riots in March in Lhasa, Tibet’s capital, were brutally put down. Shaken by reports of anti-Chinese attacks, the Dalai Lama threatened to resign unless his followers stopped their violence.

That was followed by the Beijing Olympics, which many Tibetan activists had hoped would offer the best stage in years for demonstrations. Instead, protests in Europe during the Olympic torch run faded into near-silence after China was hammered by an earthquake.

The lack of protests, in turn, helped reinforce divisions between Tibetan exiles who back the Dalai Lama’s relentless pacifism and a far angrier young generation, many born in exile, increasingly desperate for action.

Most importantly, though, there is the Dalai Lama, 73. While people close to him insist he remains in good health for his age, he has been hospitalized twice since August and his travel schedule has been curtailed.

In a movement that often sways between centuries, it can be hard to differentiate between the Tibetan struggle at large and the Dalai Lama himself.

On one side there is a modern protest movement, with Web sites and hip T-shirts and Richard Gere speeches. On the other is a leader who came to power because Buddhist mystics proclaimed him the reincarnation of the previous Dalai Lama. He is a holy man who became a master at public relations, and who remains a god to his followers.

“I have heard of this middle way, but I don’t know much about it,” said a former businessman, his hair combed into a pompadour, waiting recently in a Dharamsala refugee center.

Days earlier, he had fled Tibet, fearing the police because he’d joined the March protests. He asked that his name not be used out of concern for his family.

As for the conference, he wasn’t worrying about it: “I will do what His Holiness wants, no matter what.”

Father’s Day, as celebrated around the world, has its roots in the early 20th century US. In 1910, the state of Washington marked the world’s first official Father’s Day. Later, in 1972, then-US president Richard Nixon signed a proclamation establishing the third Sunday of June as a national holiday honoring fathers. Many countries have since followed suit, adopting the same date. In Taiwan, the celebration takes a different form — both in timing and meaning. Taiwan’s Father’s Day falls on Aug. 8, a date chosen not for historical events, but for the beauty of language. In Mandarin, “eight eight” is pronounced

In a recent essay, “How Taiwan Lost Trump,” a former adviser to US President Donald Trump, Christian Whiton, accuses Taiwan of diplomatic incompetence — claiming Taipei failed to reach out to Trump, botched trade negotiations and mishandled its defense posture. Whiton’s narrative overlooks a fundamental truth: Taiwan was never in a position to “win” Trump’s favor in the first place. The playing field was asymmetrical from the outset, dominated by a transactional US president on one side and the looming threat of Chinese coercion on the other. From the outset of his second term, which began in January, Trump reaffirmed his

Having lived through former British prime minister Boris Johnson’s tumultuous and scandal-ridden administration, the last place I had expected to come face-to-face with “Mr Brexit” was in a hotel ballroom in Taipei. Should I have been so surprised? Over the past few years, Taiwan has unfortunately become the destination of choice for washed-up Western politicians to turn up long after their political careers have ended, making grandiose speeches in exchange for extraordinarily large paychecks far exceeding the annual salary of all but the wealthiest of Taiwan’s business tycoons. Taiwan’s pursuit of bygone politicians with little to no influence in their home

Despite calls to the contrary from their respective powerful neighbors, Taiwan and Somaliland continue to expand their relationship, endowing it with important new prospects. Fitting into this bigger picture is the historic Coast Guard Cooperation Agreement signed last month. The common goal is to move the already strong bilateral relationship toward operational cooperation, with significant and tangible mutual benefits to be observed. Essentially, the new agreement commits the parties to a course of conduct that is expressed in three fundamental activities: cooperation, intelligence sharing and technology transfer. This reflects the desire — shared by both nations — to achieve strategic results within