Despite the breakdown of UN climate-change talks in Bali last December, the same themes were still being pushed at this week’s meeting in Ghana — but now developing countries have begun to question the effects on the world’s poorest.

Although he recognizes that vulnerability to climate is a result of poverty, Yvo de Boer, executive secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, had stated he wanted to focus on emissions reductions, to slow down or even halt climate change. This is the standard UN line, strongly supported by the EU and Japan, among others. Not everyone was so keen.

“It is clear that mitigation cannot be a priority for developing countries any more. Adaptation is clearly the way forward,” Ghanaian representative William Agyeman-Bonsu said.

Indeed, nearly all the Least Developed Countries were far more interested in coping with current and future conditions rather than sacrificing economic growth at the altar of emissions reductions, especially when India’s and China’s growth make the idea redundant.

Many of the predicted impacts of climate change, from increased flooding to the spread of infectious diseases, have long been around, killing kill millions of people every year — particularly the poorest.

For poor countries it is therefore essential that climate change policy does not undermine the biggest anti-poverty weapon of all, economic growth. How governments respond, trying to adapt to climate change or trying to stop it, will make all the difference. The UN has claimed that foreign aid can help, but Africa’s countless aid-financed infrastructure projects, riddled with corruption and waste, demonstrate otherwise.

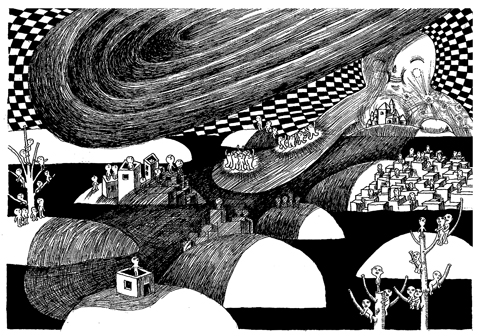

Many have attributed this week’s images of torn bridges and flooded farmlands in Sandema in northern Ghana to climate change. In reality, flooding is a seasonal event that has been occurring for centuries. Farmers suffer in this region because a lack of other jobs forces them to remain in the low-lying basins of the White Volta. So their real problem is poverty, not climate.

Their plight is exacerbated by the cyclical Bagre Dam spillages from neighboring Burkina Faso. From the beginning, the two countries did not work together, relying instead on a badly managed foreign aid package.

It is easy to see why poor countries are skeptical about spending billions of dollars on emissions reduction when similar amounts could improve the infrastructure that keeps the weather at bay — dams, flood defenses, drainage and so on. For many, discussing the future seems irrelevant when the present is so bleak.

De Boer also spoke of the need to stop deforestation as part of climate mitigation strategies. The issues are similar. Ghana has lost half its forests over the past 50 years to slash-and-burn agriculture and logging, with Sandema being one of the worst affected areas.

Local people are best placed to prevent the disappearance of forests — but to do so, they need to know that conservation will work with, not against, their economic well-being. Tourism and the wider leisure industry have proved successful in checking deforestation in the Caribbean, while plantation forestry and lumber management have achieved similar outcomes in Japan, Indonesia and Argentina.

The common factor has been the promotion of clearly defined, and often transferable, property rights. Rights over natural resources empower individuals and communities, meaning those best equipped to conserve their surroundings have an incentive to do so.

Such property rights, together with the rule of law, also have the wider effect of bringing economic growth, which reduces climate vulnerability — especially vulnerability to the diseases that kill millions right now. Governments and international organizations need to focus on true sustainable development, the kind that helps both the environment and the people who live in it.

Climate mitigation schemes, in contrast, are too often dreamed up by bureaucrats with little appreciation of the local situation. The Nigerian government, for example, recently announced its intention to generate 20 percent of energy from renewable sources by 2012, forgetting that the vast majority of its people rely on noxious fuels like wood or dung because they have no access to existing electricity, let alone any future schemes. Nigeria has recently spent more than US$10 billion, according to some estimates, on an energy program that has added zero megawatts to existing supply.

People need electricity now, not pipe dreams: sustainable bio-mass fuels, meaning dung and wood, kill at least 1.6 million children a year, the WHO says.

The world’s poorest countries must continue to fight for greater realism in the climate debate: Their livings and even their lives depend on it.

Franklin Cudjoe and Bright Simons are executive director and director of development respectively at the IMANI Center for Education & Policy in Ghana.

The US Senate’s passage of the 2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), which urges Taiwan’s inclusion in the Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercise and allocates US$1 billion in military aid, marks yet another milestone in Washington’s growing support for Taipei. On paper, it reflects the steadiness of US commitment, but beneath this show of solidarity lies contradiction. While the US Congress builds a stable, bipartisan architecture of deterrence, US President Donald Trump repeatedly undercuts it through erratic decisions and transactional diplomacy. This dissonance not only weakens the US’ credibility abroad — it also fractures public trust within Taiwan. For decades,

In 1976, the Gang of Four was ousted. The Gang of Four was a leftist political group comprising Chinese Communist Party (CCP) members: Jiang Qing (江青), its leading figure and Mao Zedong’s (毛澤東) last wife; Zhang Chunqiao (張春橋); Yao Wenyuan (姚文元); and Wang Hongwen (王洪文). The four wielded supreme power during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), but when Mao died, they were overthrown and charged with crimes against China in what was in essence a political coup of the right against the left. The same type of thing might be happening again as the CCP has expelled nine top generals. Rather than a

Former Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmaker Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) on Saturday won the party’s chairperson election with 65,122 votes, or 50.15 percent of the votes, becoming the second woman in the seat and the first to have switched allegiance from the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) to the KMT. Cheng, running for the top KMT position for the first time, had been termed a “dark horse,” while the biggest contender was former Taipei mayor Hau Lung-bin (郝龍斌), considered by many to represent the party’s establishment elite. Hau also has substantial experience in government and in the KMT. Cheng joined the Wild Lily Student

Taipei stands as one of the safest capital cities the world. Taiwan has exceptionally low crime rates — lower than many European nations — and is one of Asia’s leading democracies, respected for its rule of law and commitment to human rights. It is among the few Asian countries to have given legal effect to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant of Social Economic and Cultural Rights. Yet Taiwan continues to uphold the death penalty. This year, the government has taken a number of regressive steps: Executions have resumed, proposals for harsher prison sentences