he US' self-confidence is on the wane.

It is not just that the economy seems to be in a recession, although that is no doubt a big part of it. Foreign policy reversals and worries that the US cannot compete in a changing world also play a role.

Similar fears have arisen before and have eventually been proved wrong. But that has always taken time, perhaps because such deep fears can be self-fulfilling as both businesses and consumers cut back spending -- something that appears to be happening now.

Evidence of the loss of confidence came last week when the Conference Board released its consumer confidence survey for last month. What stood out was how far economic expectations have fallen.

The amount of pessimism -- as shown by people who forecast things will get worse -- is not quite at record highs. But the amount of optimism that things will get better is as low as it has been in the four decades that the Conference Board has been asking questions.

Why is that? It is not just the decline in home prices and the increase in mortgage defaults. Nor is the seemingly interminable war in Iraq the major cause, although it, too, is probably playing a role.

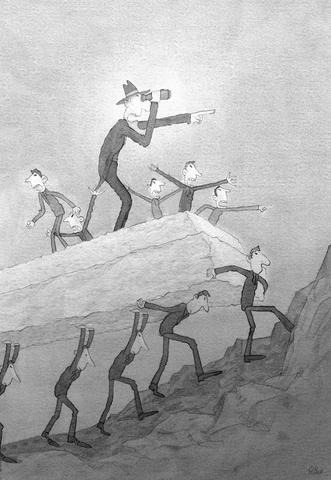

Instead, it is evidence that the US is no longer a leader, or perhaps even competent, in one area in which we believed it excelled.

That area is finance. Only months ago, US financial institutions were pre-eminent in the world economy. It was the country that invented all the new financial products and made lots of money from them. It was US investment banks that were called upon to advise companies and governments in other countries, and then to arrange the financing they needed.

Now that reputation lies in tatters. Our big banks have been forced to turn to places like China and Abu Dhabi for capital as losses have mounted. But no similar angel turned up for Bear Stearns, and the US Federal Reserve Board had to step in to avert disaster.

The Fed, which only months ago seemed omniscient, now seems to be making it up as it goes along.

Perhaps the most similar loss of confidence -- at least since the end of the Great Depression -- came in late 1973, when a sudden increase in the price of oil brought on a severe recession. The continuing war in Vietnam also hurt confidence, and then-US president Richard Nixon was under siege in the Watergate scandal, which led to his resignation the following year.

It was in December 1973 that the Conference Board's consumer expectations index hit the lowest level ever, 45.2. Last week's reading, 47.9, ranks second.

In some ways, there is even less optimism now than there was then. A lower proportion of those surveyed expect business conditions to improve within six months, and the percentage of people who think their own income will rise is much lower now than it was then.

Only in jobs is there more optimism now, and the difference is small.

The other time that is comparable in terms of a loss of confidence was early 1980, when the country was facing a new recession and imposing credit controls in what seemed to be a panicky -- and unsuccessful -- response to rising inflation. The Iranian hostage crisis seemed insoluble and then-US president Jimmy Carter was facing a primary challenge within his own party.

Expectations also declined in 1990, although not quite as far. That came after the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait and amid worries about a seeming inability to compete with Japan, whose economic success was envied and resented. In fact, the Japanese bubble was bursting, but that was not clear then.

US Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson has tried to be reassuring. But squabbling in Washington over what should be done may have contributed to a sense of drift.

In a speech last month, Paulson dismissed as "not yet ready for the starting gate" some proposals by congressional Democrats.

He said he was trying to avoid "unnecessary capital market turmoil," which seemed to imply he had no problem with necessary turmoil, and he cautioned against efforts to "slow the housing correction" that he deemed healthy.

That statement may not have encouraged fearful homeowners.

"I am constantly asked how much longer will this take to play out and if this is the worst period of market stress I have experienced," he said in a speech to a Chamber of Commerce group.

"I respond that every period of prolonged turbulence seems to be the worst until it is resolved. And it always is resolved," he said.

"Our economy and our capital markets are flexible and resilient, and I have great confidence in them," he said.

That confidence is not shared by many in the public, however.

Nor is it only consumers who are scared. Corporate executives tell pollsters they are worried and are cutting back on capital spending. Many, according to a poll of chief financial officers by Duke University and CFO magazine, think the recession will not end until next year.

By then, there will be a new US president. And the political seers may want to note that the Conference Board's expectation index, which dates to 1967, has fallen below 60 in just 10 surveys before this year -- in 1973 to 1974, 1980 and 1990 to 1991.

In the presidential election after each of those crises of confidence, the incumbent party lost the White House.

When it became clear that the world was entering a new era with a radical change in the US’ global stance in US President Donald Trump’s second term, many in Taiwan were concerned about what this meant for the nation’s defense against China. Instability and disruption are dangerous. Chaos introduces unknowns. There was a sense that the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) might have a point with its tendency not to trust the US. The world order is certainly changing, but concerns about the implications for Taiwan of this disruption left many blind to how the same forces might also weaken

As the new year dawns, Taiwan faces a range of external uncertainties that could impact the safety and prosperity of its people and reverberate in its politics. Here are a few key questions that could spill over into Taiwan in the year ahead. WILL THE AI BUBBLE POP? The global AI boom supported Taiwan’s significant economic expansion in 2025. Taiwan’s economy grew over 7 percent and set records for exports, imports, and trade surplus. There is a brewing debate among investors about whether the AI boom will carry forward into 2026. Skeptics warn that AI-led global equity markets are overvalued and overleveraged

Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi on Monday announced that she would dissolve parliament on Friday. Although the snap election on Feb. 8 might appear to be a domestic affair, it would have real implications for Taiwan and regional security. Whether the Takaichi-led coalition can advance a stronger security policy lies in not just gaining enough seats in parliament to pass legislation, but also in a public mandate to push forward reforms to upgrade the Japanese military. As one of Taiwan’s closest neighbors, a boost in Japan’s defense capabilities would serve as a strong deterrent to China in acting unilaterally in the

Taiwan last week finally reached a trade agreement with the US, reducing tariffs on Taiwanese goods to 15 percent, without stacking them on existing levies, from the 20 percent rate announced by US President Donald Trump’s administration in August last year. Taiwan also became the first country to secure most-favored-nation treatment for semiconductor and related suppliers under Section 232 of the US Trade Expansion Act. In return, Taiwanese chipmakers, electronics manufacturing service providers and other technology companies would invest US$250 billion in the US, while the government would provide credit guarantees of up to US$250 billion to support Taiwanese firms