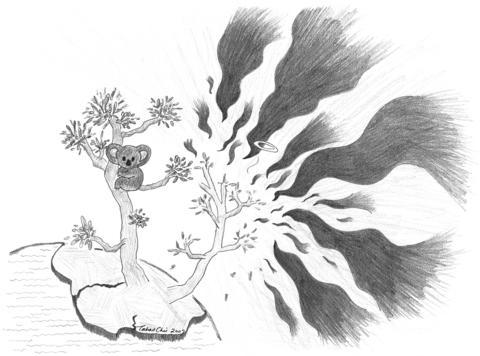

Extreme drought, ferocious bushfires and urban development are killing Australia's koalas and could push the species towards extinction within a decade, environmentalists are warning.

Alarms about the demise of the iconic and peculiar animal, which sleeps about 20 hours per day and eats only the leaves of the eucalyptus tree, have been raised before.

But Deborah Tabart, chief executive officer of the Australia Koala Foundation, believes the animal's plight is as bad as she has seen it in her 20 years as a koala advocate.

"In southeast Queensland we had them listed as a vulnerable species which could go to extinction within 10 years. That could now be seven years," she said. "The koala's future is obviously bleak."

Southeastern Queensland has the strongest koala populations in the vast country, meaning extinction in this area spells disaster for the future of the species, Tabart said.

The biggest threat is the loss of habitat as a result of road building and development on Australia's eastern coast -- traditional koala country. The joke, Tabart said, is that koalas enjoy good real estate and are often pushed out of their habitat by farming or development.

"I've driven pretty much the whole country and I just see environmental vandalism and destruction everywhere I go," she said. "It's a very sorry tale. There are [koala] management problems all over the country."

Massive bushfires which raged in the country's south for weeks during the Australian summer, burning a million hectares of land, would also have killed thousands of koalas.

Meanwhile there is the worst drought in a century, genetic mutations from decades of inbreeding in some populations, and the widespread incidence of chlamydia, a type of venereal disease which affects fertility, to further cut koala numbers.

Moreover, the animals are often fatally attacked by pet dogs.

"In southeast Queensland the koalas are just in people's backyards and the dogs just munch on them," Tabart said.

Confusing the issue is the lack of data on the number of koalas in the wild. Figures range from 100,000 animals to several million. What is known is that there were once millions of them ranged along eastern Australia.

The hunting and slaughter for their furs in the 1920s eradicated the species in the state of South Australia and pushed Victorian populations close to extinction.

Public outrage over the killing of the big-eyed "bears" put an end to the practice but Victorian stocks were unfortunately later replenished with in-bred animals, leading to a lack of genetic diversity in that state.

As a result, genetic problems such as missing testicles and deformed "pin" heads have emerged in Victorian koalas, said University of Queensland academic Frank Carrick.

Carrick, who leads a koala study project at the university, estimates the national population of the marsupial at about 1 million. And while he doesn't believe the animal will be extinct within a decade, he acknowledges that numbers are contracting.

"Though we don't really have an accurate figure on how many koalas there are in Australia right now, we do know one thing -- that it's going down. Because we keep chopping down trees and their food source," he said.

Carrick said it will take 40 to 50 years for the koala to sufficiently recover from the impact of the latest Victorian bushfires, drought and development.

"Exactly how small do we want the population to be before we push the panic button?" he said.

Dan Lunney, a senior research scientist with the New South Wales (NSW) state Department of Environment and Conservation, said koalas cover roughly the same territory as they did 20 years ago.

In some areas -- Victoria state and Kangaroo Island in South Australia -- koala numbers are growing. But in New South Wales, which tracks the east coast of Australia, the koala is a recognized threatened species.

"That means if nothing is done about it the population will continue to decline," he said. "The issue is not how many there are; but it's whether they are declining or not."

Lunney said while the Victoria bushfires would have killed large numbers of animals, as long as some koalas survived and sufficient bush regrowth is maintained, the population will recover.

"Koalas can take a fair bit. That's why we've still got them," he said. "But they do have a threshold at which they can't continue."

Lunney said populations were at most risk of dying out in areas where new houses were being built, putting them at risk of death by cars and dogs.

"Koalas in the NSW coastal areas are the most vulnerable because that's where the human population is increasing," he said.

"As the human population increases on the North Coast, the cost is coming out in the survival of koalas. Road kill -- it's a common way to see wildlife," Lunney said.

Drought, fire and flood have always been part of the Australian environment, "but when your habitat is fragmented, all these things are exacerbated," said Erna Walraven, senior curator at Sydney's Taronga Zoo.

Walraven sees the koala as a flagship species, with the health of their populations serving as an indicator of the wider health of the wildlife of the bush, including bandicoots and wallabies.

"My view is that there are a range of animals under that five, six, seven kilogram range that really [are] quite vulnerable to increased development and land clearing on the coast," she said. "I think that the koala is in there with a big suite of other species, native Australian icons, that are under threat."

When former president Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) first took office in 2016, she set ambitious goals for remaking the energy mix in Taiwan. At the core of this effort was a significant expansion of the percentage of renewable energy generated to keep pace with growing domestic and global demands to reduce emissions. This effort met with broad bipartisan support as all three major parties placed expanding renewable energy at the center of their energy platforms. However, over the past several years partisanship has become a major headwind in realizing a set of energy goals that all three parties profess to want. Tsai

An elderly mother and her daughter were found dead in Kaohsiung after having not been seen for several days, discovered only when a foul odor began to spread and drew neighbors’ attention. There have been many similar cases, but it is particularly troubling that some of the victims were excluded from the social welfare safety net because they did not meet eligibility criteria. According to media reports, the middle-aged daughter had sought help from the local borough warden. Although the warden did step in, many services were unavailable without out-of-pocket payments due to issues with eligibility, leaving the warden’s hands

Indian Ministry of External Affairs spokesman Randhir Jaiswal told a news conference on Jan. 9, in response to China’s latest round of live-fire exercises in the Taiwan Strait: “India has an abiding interest in peace and stability in the region, in view of our trade, economic, people-to-people and maritime interests. We urge all parties to exercise restraint, avoid unilateral actions and resolve issues peacefully without threat or use of force.” The statement set a firm tone at the beginning of the year for India-Taiwan relations, and reflects New Delhi’s recognition of shared interests and the strategic importance of regional stability. While India

A survey released on Wednesday by the Taiwan Inspiration Association (TIA) offered a stark look into public feeling on national security. Its results indicate concern over the nation’s defensive capability as well as skepticism about the government’s ability to safeguard it. Slightly more than 70 percent of respondents said they do not believe Taiwan has sufficient capacity to defend itself in the event of war, saying there is a lack of advanced military hardware. At the same time, 62.5 percent opposed the opposition’s efforts to block the government’s NT$1.25 trillion (US$39.6 billion) special defense budget. More than half of respondents — 56.4