China's remarkable growth has been financed recently by a rapid expansion of money and bank credit that is producing an increasingly unsustainable investment boom. This renews concerns that the country may not be able to avert a replay of the painful boom?and-bust cycle such as the one it endured in the mid-1990s.

Monetary policy is usually the first line of defense in such situations. But China's monetary policy has been hamstrung by the tightly managed exchange-rate regime. This regime prevents the central bank -- the People's Bank of China -- from taking appropriate policy decisions to manage domestic demand, because interest-rate hikes could encourage capital inflows and put further pressure on the exchange rate.

There is, of course, a vigorous ongoing debate about China's exchange-rate policy. China's rising trade surplus has led some observers to call for a revaluation of the yuan to correct what they see as an unfair competitive advantage that China maintains in international markets. Others argue that the stable exchange rate fosters macroeconomic stability in China. But this debate misses the point.

What China really needs is a truly independent monetary policy oriented to domestic objectives. This would enable the central bank to manage domestic demand by allowing interest rates to rise in order to rein in credit growth and deter reckless investment. An independent monetary policy requires a flexible exchange rate, not a revaluation. But what could take the place of the stable exchange rate as an anchor for monetary policy and for tying down inflation expectations?

We recommend a low inflation objective as the anchor for monetary policy in China. Theoretical research and the practical experiences of many countries both show that focusing on price stability is the best way for monetary policy to achieve the broader objectives in the charter of the central bank: macroeconomic and financial stability, high employment growth, etc.

The low inflation objective need not involve the formalities of an inflation-targeting regime, such as that practiced by the European Central Bank and the Bank of England, and is similar in approach to that recommended for the US by Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke.

How could such a framework be operated effectively in an economy in which financial sector problems have weakened the monetary transmission mechanism? This is a key concern because, notwithstanding recent reforms, the banking system remains fragile. Nevertheless, we believe that a minimal set of financial sector reforms -- essentially making banks' balance sheets strong enough to withstand substantial interest-rate policy actions -- should suffice to implement a low inflation objective.

Although full modernization of the financial sector is a long way off even in the best of circumstances, the minimal reforms that we recommend could strengthen the banking system sufficiently in the near term to support a more flexible exchange rate anchored by an inflation objective. Indeed, price stability, and the broader macroeconomic stability emanating from it, would provide a good foundation for pushing forward with other financial sector reforms.

The framework we suggest has the important benefit of continuity. The central bank would not have to change its operational approach to monetary policy. Only a shift in strategic focus would be needed to anchor monetary policy with a long-run target range for low inflation. Monitoring of monetary (and credit) targets would still be important in achieving the inflation objective. Furthermore, it should be easier to adopt the new framework when times are good -- like now, when growth is strong and inflation is low.

There is some risk that appreciation of the exchange rate, if greater flexibility were allowed, could precipitate deflation. What this really highlights, however, is the importance of framing the debate about exchange-rate flexibility in a broader context. Having an independent monetary policy that could counteract boom-and-bust cycles would be the best way for China to deal with such risks.

Contrary to those who regard the discussion of an alternative monetary framework as premature, there are good reasons for China to begin right now to build the institutional foundation for the transition to an independent monetary policy. Indeed, early adoption of a low inflation objective would help secure the monetary and financial stability that China needs as it allows greater exchange-rate flexibility.

Marvin Goodfriend is a professor at the Tepper School of Business at Carnegie-Mellon University and was previously senior vice president and policy adviser at the US Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, Virginia. Eswar Prasad is chief of the Financial Studies Division in the IMF's Research Department. Copyright: Project Syndicate

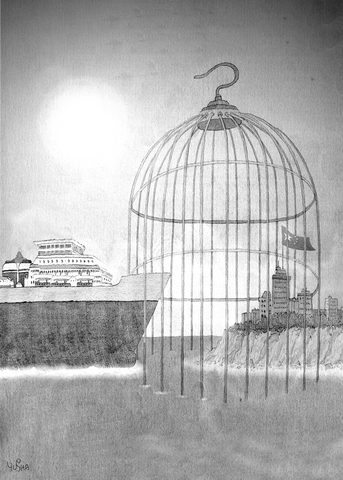

We are used to hearing that whenever something happens, it means Taiwan is about to fall to China. Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) cannot change the color of his socks without China experts claiming it means an invasion is imminent. So, it is no surprise that what happened in Venezuela over the weekend triggered the knee-jerk reaction of saying that Taiwan is next. That is not an opinion on whether US President Donald Trump was right to remove Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro the way he did or if it is good for Venezuela and the world. There are other, more qualified

The immediate response in Taiwan to the extraction of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro by the US over the weekend was to say that it was an example of violence by a major power against a smaller nation and that, as such, it gave Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) carte blanche to invade Taiwan. That assessment is vastly oversimplistic and, on more sober reflection, likely incorrect. Generally speaking, there are three basic interpretations from commentators in Taiwan. The first is that the US is no longer interested in what is happening beyond its own backyard, and no longer preoccupied with regions in other

As technological change sweeps across the world, the focus of education has undergone an inevitable shift toward artificial intelligence (AI) and digital learning. However, the HundrED Global Collection 2026 report has a message that Taiwanese society and education policymakers would do well to reflect on. In the age of AI, the scarcest resource in education is not advanced computing power, but people; and the most urgent global educational crisis is not technological backwardness, but teacher well-being and retention. Covering 52 countries, the report from HundrED, a Finnish nonprofit that reviews and compiles innovative solutions in education from around the world, highlights a

A recent piece of international news has drawn surprisingly little attention, yet it deserves far closer scrutiny. German industrial heavyweight Siemens Mobility has reportedly outmaneuvered long-entrenched Chinese competitors in Southeast Asian infrastructure to secure a strategic partnership with Vietnam’s largest private conglomerate, Vingroup. The agreement positions Siemens to participate in the construction of a high-speed rail link between Hanoi and Ha Long Bay. German media were blunt in their assessment: This was not merely a commercial win, but has symbolic significance in “reshaping geopolitical influence.” At first glance, this might look like a routine outcome of corporate bidding. However, placed in