Europe's sigh of relief at the supposed end of the dispute between Russia and Ukraine over gas pricing was audible here in Kiev. But the settlement raises more questions than it answers. By placing Ukraine's energy needs in the hands of a shadowy company linked to international criminals, the agreement has planted the seeds of new and perhaps more dangerous crises.

As a result, I am challenging this deal in court. Let a public hearing before a judge reveal exactly who will benefit from this deal.

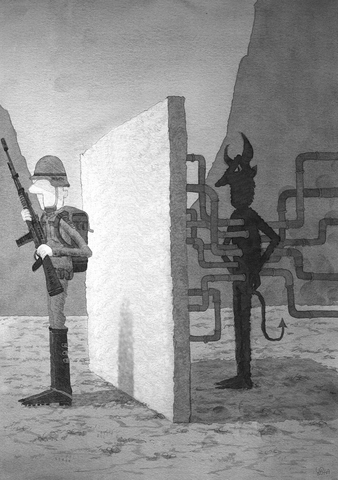

The settlement between Ukraine and Russia's state-owned gas monopoly, Gazprom, is intolerable because Ukraine's energy future has been placed in the hands of RosUkrEnergo, a criminal canker on the body of our state gas corporation. RosUkrEnergo was established in the last months of the regime of our former ruler, Leonid Kuchma. Yet it miraculously gained control of all of Ukraine's gas imports from Central Asia. Under the deal agreed this week, it retains that control.

As one who worked in the gas industry before entering politics, I know that the gas trade in the countries of the former Soviet Union is riddled with corruption. During my premiership, my government sought to investigate RosUkrEnergo -- to discover who precisely its owners are, how it gained a virtual monopoly on the import of Central Asian gas, and where its profits go. Now that I am not in government, that investigation has been shelved. Ukraine's energy needs, and thus the certainty of energy supplies across Europe, will never be secure as long as gas transit is in the hands of secretive companies with unknown owners.

But the issues raised by the gas dispute between Ukraine and Russia go beyond energy security, reviving questions about Ukraine's place in Europe and the world. As this struggle shows, Ukraine has been obliged to assume a higher-profile role in European affairs. It must consider where and in what sort of Europe it fits, what balance it should strike between Russia and the EU, and how it should find the self-assurance needed to play its full part in world affairs.

It would be sheer folly to suggest that Ukrainians start with a blank slate. Centuries of being part of the Russian and Soviet empires have, in different ways, shaped how Ukrainians view their country and its interests. One consequence of this is that Ukrainians are often shy about asserting Ukraine's independent interests plainly -- exemplified by Ukraine's acceptance of a deal that leaves its energy future so insecure.

Like any country, Ukraine's relations with the world are determined by four interlocking factors: history, patriotism, national interests and geography. Each factor has special resonance here. True, Ukrainians rightly feel like citizens of a normal, independent country and want to be treated that way. But this does not mean we want to bury history and our historic ties. We are a normal country with an abnormal history.

Indeed, Ukraine's interests form a comfortingly familiar triangle of economic, political and strategic priorities: free trade and open markets across the globe; prosperous and democratic neighbors; and not being on the front-line of a conflict, still less a potential battleground, between Russia and the West. Our goal is thus a democratic Ukraine located between prosperous like-minded neighbors to the east and west.

Of course, the risk of tyranny, turmoil and war within the so-called "post-Soviet space" is large, leaving Ukraine keen to limit its vulnerability. Ukrainian enthusiasm about the EU is based on the idea that European security is indivisible.

We recognize, of course, that few of even the most fervent supporters of European integration want to help Ukraine quickly become a member. But the risk to EU gas supplies shows that our fates are linked. Europe must play its part as Ukraine redefines its historic ties to Russia, and its actions must do nothing to undermine Ukraine's national independence -- or, indeed, that of any of the countries that emerged from the Soviet Union's breakup.

The proposed Baltic Sea pipeline, which would bring gas to Germany directly from Russia, bypassing Poland, Ukraine, the Baltic states and the rest of Central Europe, is dangerous in this regard, because it may allow Gazprom the freedom to cut gas supplies to customers without endangering supplies to its favored western markets. That is a recipe for renewed threats, not only to Ukraine, but to EU members like Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia, Slovenia and the three Baltic states.

In broad terms, Ukraine seeks security and stability, and it should be remembered that our record here is strong. Our decision more than a decade ago to surrender Ukraine's status as a nuclear nation is the clearest sign of our good neighborly intentions and political maturity.

Today's crisis over gas supplies must not be overblown. Objectively speaking, Ukraine today is more secure as a nation than at any time in its history. But Ukrainians do not feel as secure as they should.

The way to deal with uncertainty and complex situations is to think clearly and act decisively, not cut deals that place Ukraine's future in the hands of shadowy businesses. Only by clearly articulating and defending Ukraine's national interests can today's dispute over gas supplies establish our role in a transformed Europe.

Yuliya Tymoshenko is a former prime minister of Ukraine.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

The saga of Sarah Dzafce, the disgraced former Miss Finland, is far more significant than a mere beauty pageant controversy. It serves as a potent and painful contemporary lesson in global cultural ethics and the absolute necessity of racial respect. Her public career was instantly pulverized not by a lapse in judgement, but by a deliberate act of racial hostility, the flames of which swiftly encircled the globe. The offensive action was simple, yet profoundly provocative: a 15-second video in which Dzafce performed the infamous “slanted eyes” gesture — a crude, historically loaded caricature of East Asian features used in Western

Is a new foreign partner for Taiwan emerging in the Middle East? Last week, Taiwanese media reported that Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Francois Wu (吳志中) secretly visited Israel, a country with whom Taiwan has long shared unofficial relations but which has approached those relations cautiously. In the wake of China’s implicit but clear support for Hamas and Iran in the wake of the October 2023 assault on Israel, Jerusalem’s calculus may be changing. Both small countries facing literal existential threats, Israel and Taiwan have much to gain from closer ties. In his recent op-ed for the Washington Post, President William

A stabbing attack inside and near two busy Taipei MRT stations on Friday evening shocked the nation and made headlines in many foreign and local news media, as such indiscriminate attacks are rare in Taiwan. Four people died, including the 27-year-old suspect, and 11 people sustained injuries. At Taipei Main Station, the suspect threw smoke grenades near two exits and fatally stabbed one person who tried to stop him. He later made his way to Eslite Spectrum Nanxi department store near Zhongshan MRT Station, where he threw more smoke grenades and fatally stabbed a person on a scooter by the roadside.

Taiwan-India relations appear to have been put on the back burner this year, including on Taiwan’s side. Geopolitical pressures have compelled both countries to recalibrate their priorities, even as their core security challenges remain unchanged. However, what is striking is the visible decline in the attention India once received from Taiwan. The absence of the annual Diwali celebrations for the Indian community and the lack of a commemoration marking the 30-year anniversary of the representative offices, the India Taipei Association and the Taipei Economic and Cultural Center, speak volumes and raise serious questions about whether Taiwan still has a coherent India