A year ago, we were told we had 12 months to make poverty history. So, in the bleary cold light of the new year, how does our achievement stack up? Did a year of unprecedented focus on Africa -- rock concerts, 250,000 demonstrating in Edinburgh and an extraordinary degree of political engagement at the highest levels -- succeed?

In recent weeks there has been no shortage of aid agencies and government advisers attempting to draw up the balance sheet. The year ended on a gloomy note. The failure in Hong Kong to achieve anything like a positive outcome for developing countries was a big blow, given that the huge costs of unfair trade dwarf the pocket-money deals on debt and aid. Even more depressing was the news from Africa.

It was not just the string of crises -- from Malawi and Zambia in famine-struck southern Africa to the fragility of the peace in Sudan and the ongoing conflict in Darfur -- but, more worryingly, the much-favored reform-minded governments of key countries such as Uganda and Ethiopia showed an ugly ruthlessness.

So the campaign fizzled out. It lost momentum in the public imagination after the London bombings in July. The politicians may have plowed on at the UN summit in New York in September, but they no longer did so under the glare of media attention.

But if you stand back from the past few months and assess the whole year, something more optimistic becomes clear: The politics of global inequality have come of age. It has become part of the mainstream in this country, in a way that was unthinkable a decade ago. In the past, third-world poverty did occasionally grab attention, but only when framed as an appeal to respond to a humanitarian crisis.

This year marked a step change in the popular understanding that global poverty is about more than dipping your hand in your pocket for the odd pound coin. The involvement of celebrities ensured slots on primetime TV and the attention of popular newspapers and reached an entirely new constituency. Issues such as trade justice, once regarded as the obscure obsessions of the hairy, the sandalled and the tattooed, are percolating through to your average supermarket shopper.

At the same time as the shift at a popular level gathered pace, last year saw the deepening of a cosy relationship between government and the aid agencies. In the 1990s, the debt campaigners labored away on the margins of the Labor party, and never dreamed of the kind of easy access to ministerial ears their successors regard as routine.

Government and aid agencies are now tied into a symbiotic -- and not unproblematic -- relationship as they bolster each other's credibility. During much of last year they were working hand-in-glove (the agencies' criticisms post-Gleneagles were a short-lived bid to scramble back some vestige of independence). They both have much at stake -- to show that campaigning can work and politicians can make a difference.

The final confirmation of this mainstreaming came when David Cameron picked development as one of his six key themes on becoming leader of Britain's opposition Conservative party, even if he did forget to deliver that bit of his memorized speech.

The point is that in British politics, having something to say about global poverty is now regarded as an essential to get the tone of your political pitch right. It hits two Cs: compassionate and contemporary.

So if the politics of global inequality have come of age, what are its ingredients?

At a political level, the rhetoric is grandiose. Any aspiring world statesman now has to deliver speeches on child mortality and talk about female literacy rates in the developing world as if they a) knew what they were on about and b) spent the early hours worrying about it. There's a new expectation of government. That's a step change from the era of Reagan and Thatcher.

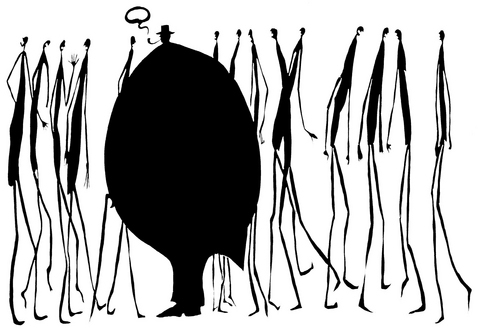

At street level, there's a vague sentimentality, a bit of emotional manipulation, a fair dollop of the consumer feel-good factor (the "I want to feel virtuous and consume"). It's not political mobilization or activism in any traditional sense, but it's enough to motivate someone to buy the white wristband and email British Prime Minister Tony Blair. It's the celebrity factor that delivers this constituency -- and that makes the likes of Bono, Bob Geldof and the film-maker Richard Curtis into a new breed of political actor. Love 'em or loathe 'em.

The big worry is that this kind of politics has no kind of sustainability. It's a flash moment, and short attention spans ensure the media has moved on to something else before the politicians' rhetoric has been translated into delivery. This is particularly pertinent to the Gleneagles aid deal, which could very uneasily come unstuck, given the huge increases in aid required from reluctant countries such as Germany and Italy -- of 106 percent and 276 percent, respectively, by 2010.

But perhaps an even bigger worry is that the politics of global inequality are characterized by a wishful naivety. Tony Blair's Commission for Africa in March last year posited its analysis of a turnaround in Africa on the existence of a new generation of African governments.

From the start, some argued there was no such thing, and their voices have only grown louder in the summer, as the Ethiopian government, whose president was a member of the commission, shot dozens of demonstrators and detained thousands. More recently, criticism of Uganda's President Yoweri Museveni has come to a head over the imprisonment of an opposition leader.

A batch of books this year, including Matthew Lockwood's stinging analysis The State They're In and Martin Meredith's history of the past 50 years in Africa, point to the fact that most African governments have a poor, often abysmal, record of delivering development, and there's little reason to believe that has changed.

So there is fat chance that last year made poverty history. It finally offered a decent debt deal after 20 years of campaigning; there was a promise, yet to be fulfilled, to double aid by 2010; and there was a surprise goody thrown in -- a hugely ambitious target for universal access to HIV/AIDS treatment. In terms of G8 summits, it was a big deal; in terms of a breakthrough for Africa, forget it. AIDS and climate change will ensure that the suffering of millions of Africans will plague our consciences for decades to come.

But for all its shortcomings, the coming-of-age of the politics of global inequality is being driven by an important issue that will ensure it stays on the international agenda: At its heart is a question of legitimacy.

The West's global dominance is being challenged as unjust -- whether that is by the WTO's new bloc of leading developing countries or even by the fanatical violence of the Islamist extremists. The huge wealth generated by globalization, with its equally huge ecological footprint, cannot largely be for the benefit of a tiny proportion of the world's population.

Increasingly we question our own legitimacy, as well as being called to account by others. Last year spurred a new expectation across the developed world from the new campaigns in Japan to the US that politicians have to show they do more than just talk about it. That's no small achievement.

We are used to hearing that whenever something happens, it means Taiwan is about to fall to China. Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) cannot change the color of his socks without China experts claiming it means an invasion is imminent. So, it is no surprise that what happened in Venezuela over the weekend triggered the knee-jerk reaction of saying that Taiwan is next. That is not an opinion on whether US President Donald Trump was right to remove Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro the way he did or if it is good for Venezuela and the world. There are other, more qualified

The immediate response in Taiwan to the extraction of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro by the US over the weekend was to say that it was an example of violence by a major power against a smaller nation and that, as such, it gave Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) carte blanche to invade Taiwan. That assessment is vastly oversimplistic and, on more sober reflection, likely incorrect. Generally speaking, there are three basic interpretations from commentators in Taiwan. The first is that the US is no longer interested in what is happening beyond its own backyard, and no longer preoccupied with regions in other

As technological change sweeps across the world, the focus of education has undergone an inevitable shift toward artificial intelligence (AI) and digital learning. However, the HundrED Global Collection 2026 report has a message that Taiwanese society and education policymakers would do well to reflect on. In the age of AI, the scarcest resource in education is not advanced computing power, but people; and the most urgent global educational crisis is not technological backwardness, but teacher well-being and retention. Covering 52 countries, the report from HundrED, a Finnish nonprofit that reviews and compiles innovative solutions in education from around the world, highlights a

A recent piece of international news has drawn surprisingly little attention, yet it deserves far closer scrutiny. German industrial heavyweight Siemens Mobility has reportedly outmaneuvered long-entrenched Chinese competitors in Southeast Asian infrastructure to secure a strategic partnership with Vietnam’s largest private conglomerate, Vingroup. The agreement positions Siemens to participate in the construction of a high-speed rail link between Hanoi and Ha Long Bay. German media were blunt in their assessment: This was not merely a commercial win, but has symbolic significance in “reshaping geopolitical influence.” At first glance, this might look like a routine outcome of corporate bidding. However, placed in