What does last week's US Supreme Court ruling mean -- for individual file-sharers and for the future of the Internet in general?

The court judgment against Grokster and StreamCast rules that those producing file-sharing programs can be held liable for copyright infringement may actually lead to a reduction in the industry's unpopular prosecutions of individual downloaders -- although it's also likely to make the software harder to come by.

For software developers and the Web at large, activists fear that the ruling will stifle progress, making entrepreneurs wary of releasing any technology that could be used illegally. The court has "unleashed a new era of legal uncertainty on America's innovators," says Fred von Lohmann, senior intellectual property attorney for the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), which lobbies in defense of "digital freedoms."

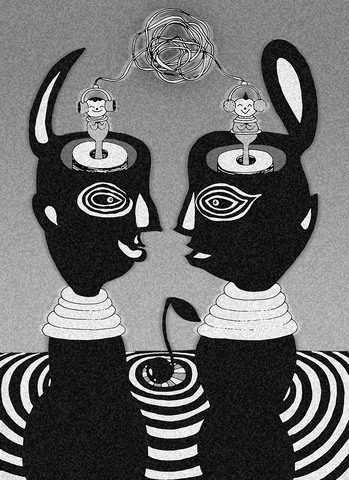

ILLUSTRATION: MOUNTAIN PEOPLE

Recent history is littered with examples of the entertainment industry panicking about technologies that ended up proving harmless -- and which might not exist today had they been subject to a ruling like this one.

"I say to you that the VCR is to the American film producer and the American public as the Boston strangler is to the woman home alone," Jack Valenti, then head of the Motion Picture Association of America, said in 1982.

Those arguments don't apply here, the court said. "There was no evidence that [the VCR manufacturer] Sony had expressed an object of bringing about taping in violation of copyright or had taken active steps to increase its profits from unlawful taping," the judges wrote.

But that seems to leave a loophole. What seems crucial is proving that the company intended to profit from lawbreaking. So another software firm might reduce the risk of a lawsuit by declaring at every possible opportunity that its product shouldn't be used illegally, and by actively encouraging legal uses.

First, is file-sharing just stealing?

Unauthorized downloading certainly infringes copyright, and copyright infringement can certainly be a crime. For the industry, that's the end of the story -- as it is for the government.

"Piracy is theft, pure and simple," British Arts Minister Estelle Morris said last year. "Whether it's Jamelia or a jobbing musician, the artist suffers. We owe it to them to make sure they get a fair return for their creativity, flair and inspiration."

You won't find many people on the pro-sharing side of the argument speaking up for total copyright anarchy. What they say is that the situation is more complicated. For a start, if it's true that downloads don't affect sales, it would be a victimless crime. (Which doesn't necessarily make it all right: the British Phonographic Industry (BPI) argues that unauthorized file-sharing would be wrong "regardless of whether a single record sale was lost").

Second, there's the argument that copyright in a work of art simply isn't the same as, say, your rights in a piece of land that you own. Patents and copyrights, from this viewpoint, have always been aimed at finding a balance -- as the Harvard professor Lawrence Lessig puts it -- "between rewarding creativity and allowing the borrowing from which new creativity springs." That's why terms of copyright eventually elapse; in the original US Constitution, they elapsed after just 17 years. Under Thomas Jefferson's original standard, it would no longer be illegal to download, for example, Madonna's 1986 album True Blue.

Finally, there's the argument that, even if unauthorized file-sharing is wrong, that doesn't make it right to prosecute downloaders. On one hand, what about proportion? It's immoral to steal an apple, but more immoral to sentence the apple-stealer to death by firing squad -- and critics might argue that prosecuting parents for their schoolchildren's downloads falls into a similar trap.

On the other hand, there's the possibility of negative consequences that outweigh the benefits. What if, as file-sharing activists argue, the Supreme Court ruling has the effect of dissuading entrepreneurs from inventing new technologies, which might otherwise benefit us all, for fear that someone might misuse them?

Also, is there any evidence that file-sharing has actually damaged CD sales?

The facts are far murkier than the record industry likes to assert.

"The unauthorized distribution of music over the Internet ... has already had an enormous effect on music sales," the BPI declares.

And music retailing is certainly in decline: CD sales have fallen by 25 percent since 1999. But is file-sharing to blame?

Some surveys seem to suggest that it is. According to one, Americans who had downloaded more than 100 files bought 61 percent fewer CDs from one year to the next. In a Canadian study, 30 percent of people who said they had bought fewer CDs in the past year admitted, without being prompted, that file-sharing was one of the reasons. But then, last year, two US economists -- studying actual downloads, instead of survey responses -- provoked fury from the industry with a statistical analysis that found a negligible impact. "Downloads have an effect on sales which is statistically indistinguishable from zero," concluded Felix Oberholzer, a Harvard Business School professor, and Carolina academic Koleman Strumpf.

Some downloaders were not "free riders," the professors argued, but "samplers." In other words, they were more likely to buy CDs as a result of having tried them out online. Many others would never have bought the CD in the first place. At worst, they wrote, "It would take 5,000 downloads to reduce the sales of an album by one copy."

Even the decline of the CD is a more intriguing tale than it may at first seem. Album sales actually reached a record high in the Britain in 2003; it's singles that have suffered the biggest catastrophe.

When it wants to deter pirates, the BPI attributes this to piracy. But in other contexts it is happy to admit to other possible causes: the shrinking gap between the cost of an album and the cost of a single, for example, along with the rise of competing forms of electronic entertainment.

Third, are the major record labels really more greedy and exploitative than any other industry?

A lot of the viciousness of the file-sharing debate hinges not on whether it's right or wrong -- but on the accusation that the record industry, through its exploitation of artists and customers, long ago gave up the right to the moral high ground it now seeks to occupy. Is that fair?

In America in 2002, the five biggest CD distributors settled a lawsuit accusing them of price-fixing, agreeing to pay back US$143 million to consumers. Then again, the Record Industry Association of America argues, CDs, in the US at least, would have doubled in price if they had kept pace with the consumer price index for much of the 1990s.

"Pricing is never used as a justification for what is effectively theft," says Matt Phillips of the BPI. "And take a step back. There's a God-given idea that CDs are too expensive, but compared to what? When people will willingly go to Starbucks and pay US$4 for a coffee then say US$14 for a CD is too expensive, it doesn't make any kind of sense to me."

As for whether the industry exploits artists, there are as many views as there are artists' contracts. It is virtually impossible to pinpoint a meaningful "average royalty" that an artist gets from a CD. If we take the extremely rough figure of 10 percent, that doesn't compare badly to what novelists get -- but then, crucially, they usually get to keep their copyright.

The industry arguably stifles creativity in other ways, too, by mega-promoting a handful of mainstream artists at the expense of others -- although, as Phillips says, it provides "the lion's share" of investment in the music world as a whole.

Fourth, how can individual file-sharers protect themselves against lawsuits?

Most obviously by not downloading music files without permission from the copyright holder. The EFF also reluctantly recommends turning off any options that allow your computer to be used as a source, rather than just a destination, for shared files, since the industry seems to be targeting those who do both.

We are used to hearing that whenever something happens, it means Taiwan is about to fall to China. Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) cannot change the color of his socks without China experts claiming it means an invasion is imminent. So, it is no surprise that what happened in Venezuela over the weekend triggered the knee-jerk reaction of saying that Taiwan is next. That is not an opinion on whether US President Donald Trump was right to remove Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro the way he did or if it is good for Venezuela and the world. There are other, more qualified

The immediate response in Taiwan to the extraction of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro by the US over the weekend was to say that it was an example of violence by a major power against a smaller nation and that, as such, it gave Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) carte blanche to invade Taiwan. That assessment is vastly oversimplistic and, on more sober reflection, likely incorrect. Generally speaking, there are three basic interpretations from commentators in Taiwan. The first is that the US is no longer interested in what is happening beyond its own backyard, and no longer preoccupied with regions in other

As technological change sweeps across the world, the focus of education has undergone an inevitable shift toward artificial intelligence (AI) and digital learning. However, the HundrED Global Collection 2026 report has a message that Taiwanese society and education policymakers would do well to reflect on. In the age of AI, the scarcest resource in education is not advanced computing power, but people; and the most urgent global educational crisis is not technological backwardness, but teacher well-being and retention. Covering 52 countries, the report from HundrED, a Finnish nonprofit that reviews and compiles innovative solutions in education from around the world, highlights a

Jan. 1 marks a decade since China repealed its one-child policy. Just 10 days before, Peng Peiyun (彭珮雲), who long oversaw the often-brutal enforcement of China’s family-planning rules, died at the age of 96, having never been held accountable for her actions. Obituaries praised Peng for being “reform-minded,” even though, in practice, she only perpetuated an utterly inhumane policy, whose consequences have barely begun to materialize. It was Vice Premier Chen Muhua (陳慕華) who first proposed the one-child policy in 1979, with the endorsement of China’s then-top leaders, Chen Yun (陳雲) and Deng Xiaoping (鄧小平), as a means of avoiding the