Mention vaccines and most people -- if they're not too busy wincing at the thought of a sharp needle plunging into their upper arm -- will think of an injection that prevents an illness such as flu, rubella or measles. Drop the C-word into conversation and talk automatically turns to chemotherapy, radiation or surgery. This could be about to change with the news that a vaccine against cervical cancer is on the way. The jab, which targets the virus that is the main cause of cervical cancer, has proved so effective in trials that it is expected to be licensed for use in the UK within five years.

Experts estimate that it will be another two decades before the vaccine eliminates the need for cervical screening, but are optimistic that it could eventually substantially reduce the incidence of the disease. It's an exciting prospect, but one which raises an important question: are we on the cusp of a new age for cancer treatment, in which preventative vaccines will become commonplace? Emphatically not, according to Richard Sullivan of Cancer Research.

"Vaccines can only be used to prevent those cancers which are caused by a virus, and there are a limited number of these," he says. These are: Those 70 percent of cervical cancers caused by the human papilloma virus (HPV); liver cancers brought on by hepatitis B; the AIDS-related cancer Kaposi's sarcoma; and Burkitt's lymphoma, which is triggered by the glandular fever virus.

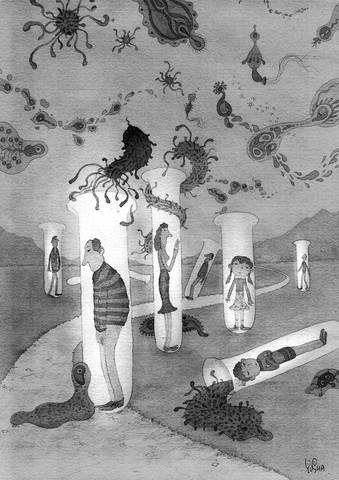

ILLUSTRATION: YUSHA

The cervical cancer vaccine -- to be marketed by GlaxoSmithKline as Ceravix and Merck as Gardasil -- protects against four types of HPV. In clinical tests, infections in those patients with the four HPV types fell by 90 percent compared with the control group. The HPV virus is mainly passed on during sexual intercourse, which is why doctors believe it would be most effective to vaccinate young girls aged between 10 and 13 before they have had any sexual experience.

Most sexually active women have the virus at some time in their lives, but for most women, most of the time the virus is knocked out by their immune system without them even being aware that they have been affected. So while it's likely that the nation's girls will be rolling up their sleeves to be administered cancer-thwarting jabs in the near future, the boys won't be joining them for injections to ward off prostate cancer, or other non-viral cancers. Nevertheless, vaccines could well have an exciting role to play in cancer treatment, but as a therapeutic, not a preventive, measure.

Scientists around the world are exploring such vaccines in a variety of cancers: melanoma, prostate, colon, renal, breast, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, non-small-cell lung and ovarian are just some of the ones being targeted. Though these are still in the experimental stage, experts are increasingly excited about the possible effect they could have on cancer recovery rates.

These therapeutic vaccines work by stimulating a response from the human immune system to help seek out and destroy cancer cells in people already diagnosed with the disease. They attempt to make the body's defense mechanism recognize there is something wrong, and to kick-start it into action to destroy the dangerous cells. Put simply, it's a question of priming the immune system in people known to be at risk (ie, those who have already been diagnosed with cancer) by injecting them with a substance that gives their body the ability to mark, and then deal with, invading malignant cells when they turn up again in the body's system.

Mary Collins, professor of immunology at University College London, has been involved in various trials of melanoma vaccines. She believes therapeutic vaccines will be particularly good at warding off recurrent skin cancers.

"This is because with melanoma it's very easy to predict the likelihood of the disease coming back with a secondary tumor," she says. "If a primary tumor is more than a certain depth, you can say with reasonable certainty that it will return."

There are two different ways of administering therapeutic vaccines, according to Angus Dalgleish, professor of oncology at St George's Hospital in London.

"There are those in which tumor antigens are injected alone, in the form of cells; or dendritic cell vaccines [named after the special class of immune cells that initiate the immune response], which collect the patient's own stem cells, isolating the dendritic cells, incubating them to make a vaccine, then returning them to the patient to `supercharge' their blood to fight the cancer," Dalgleish says.

Perhaps surprisingly, experts do not believe that cancer patients will have a problem with being reinjected with the disease that has infected their body. Professor Mary Collins says that in her experience, "patients already suffering from cancer can understand the rationale and are surprisingly keen to take part in experimental trials."

It is important to bear in mind, though, that immunotherapy will never replace traditional therapies, stresses Margaret Stanley, professor in epithelial biology at Cambridge University.

"There is absolutely never going to be just one treatment for cancer," she says. "Tumors can evade the immune system in many different ways, so it would be a case of using the vaccine in conjunction with chemotherapy, radiotherapy or surgery."

Dalgleish concurs. "Vaccines are not a one-size-fits-all approach," he says. "They do not work for everyone. In our research on therapeutic vaccines for prostate cancer, we've noticed, for example, that they seem to work best in fit, healthy people with good diets."

One thing's for sure: there's a lot more research to be done before these vaccines will be licensed and available on the open market.

"The whole field is being taken really seriously now that there's increasing evidence to show that the vaccines can induce some kind of positive response to improve survival rates," Dalgleish said.

But, "To get it right, there's a long way to go," he added.

In a stark reminder of China’s persistent territorial overreach, Pema Wangjom Thongdok, a woman from Arunachal Pradesh holding an Indian passport, was detained for 18 hours at Shanghai Pudong Airport on Nov. 24 last year. Chinese immigration officials allegedly informed her that her passport was “invalid” because she was “Chinese,” refusing to recognize her Indian citizenship and claiming Arunachal Pradesh as part of South Tibet. Officials had insisted that Thongdok, an Indian-origin UK resident traveling for a conference, was not Indian despite her valid documents. India lodged a strong diplomatic protest, summoning the Chinese charge d’affaires in Delhi and demanding

In the past 72 hours, US Senators Roger Wicker, Dan Sullivan and Ruben Gallego took to social media to publicly rebuke the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) over the defense budget. I understand that Taiwan’s head is on the chopping block, and the urgency of its security situation cannot be overstated. However, the comments from Wicker, Sullivan and Gallego suggest they have fallen victim to a sophisticated disinformation campaign orchestrated by an administration in Taipei that treats national security as a partisan weapon. The narrative fed to our allies claims the opposition is slashing the defense budget to kowtow to the Chinese

In a Taipei Times editorial published almost three years ago (“Macron goes off-piste,” April 13, 2023, page 8), French President Emmanuel Macron was criticized for comments he made immediately after meeting Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) in Beijing. Macron had spoken of the need for his country to find a path on Chinese foreign policy no longer aligned with that of the US, saying that continuing to follow the US agenda would sacrifice the EU’s strategic autonomy. At the time, Macron was criticized for gifting Xi a PR coup, and the editorial said that he had been “persuaded to run

The wrap-up press event on Feb. 1 for the new local period suspense film Murder of the Century (世紀血案), adapted from the true story of the Lin family murders (林家血案) in 1980, has sparked waves of condemnation in the past week, as well as a boycott. The film is based on the shocking, unsolved murders that occurred at then-imprisoned provincial councilor and democracy advocate Lin I-hsiung’s (林義雄) residence on Feb. 28, 1980, while Lin was detained for his participation in the Formosa Incident, in which police and protesters clashed during a pro-democracy rally in Kaohsiung organized by Formosa Magazine on Dec.