It's not often that the international press take an interest in UK politics, but they are now. Survey the back rows of the morning press conferences and you'll see reporters from across the globe, come to watch the final days of the British election campaign.

What have they noticed so far? I spoke to several struck by the aggressiveness, even downright rudeness, of the exchanges between candidates and voters.

"I have never in my life seen a head of government treated that way," one US correspondent told me, shocked by the mauling UK Prime Minister Tony Blair received from a TV audience on April 28. Calmly and coherently, people first booed Blair then told him, to his face, that he was a liar -- something no American had ever done to US President George W. Bush.

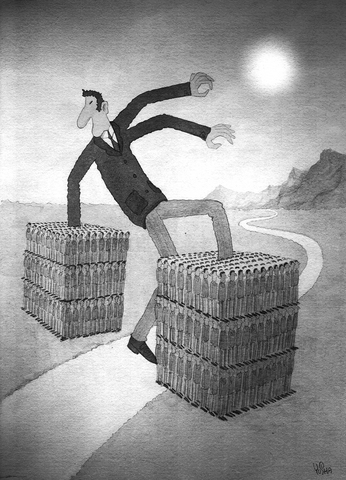

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

The foreign press have been impressed by the degree of interrogation the British party leaders face each day.

"Blair takes more questions in a morning than [Senator] John Kerry took all year," says another US colleague, envious of the British daily grilling.

The Americans particularly admire the UK's ban on paid TV advertising, which forces candidates to slug it out on "free media": news programs where they are challenged at every turn.

These musings will soon give way to the real purpose of their visits here: to report the election result. If Labour notches up a substantial victory, as most polls now predict, the foreign media will know what to say.

"Blair overcame British opposition to the war on Iraq to win a historic third term..." is the first line one correspondent imagines he'll be writing next week. That gives a useful clue to how the world will see a Labour win this week. No matter the myriad domestic considerations that are really motivating British voters, foreign capitals are bound to interpret tomorrow's election as a referendum on the war.

Some will read into Labour success proof that Iraq was just not that important to the people of the UK. They may not have liked it, but their opposition was not strong enough to make them eject a government.

Others will go further. They will interpret a Labour victory as a kind of vindication, a collective thumbs-up for the war. That's certainly how policymakers in Washington will want to see it.

Consider Bush's interview with the Washington Post shortly after his re-election last autumn. He was asked why no administration official had lost his job, why no one had been held accountable for the serial mistakes made in the conduct of the war.

The president replied that the electorate had had their "moment of accountability" the previous November. If they had wanted to punish those who had prosecuted the war, that was their chance. As he saw it, re-election was proof that the US people supported his action in Iraq. He will surely see a Blair win the same way.

Yet that would hardly be accurate. In the UK, in contrast with recent elections in the US, Spain and Australia, a pro-war government is confronted with a pro-war opposition. That makes it impossible to see May 5 as a plebiscite on the war: the choice is simply not that straightforward.

Indeed, now that Conservative opposition leader Michael Howard has said he would have supported an invasion of Iraq even if he had known the country had no weapons of mass destruction, the electorate's choice boils down to hawk or ultra-hawk. Kerry came up with some extraordinary convolutions on Iraq last year, but none as twisted as the "regime change plus" position now staked out by Howard -- which is even more at odds with international law than the one maintained by the prime minister.

No, the truer interpretation of a probable Blair triumph is that Labour will have won despite Iraq -- and despite Blair. This is quite a challenge for foreign reporters: to explain to their readers an election in which the incumbent is distrusted, even despised, by large numbers of voters -- yet on course for a comfortable victory.

The explanation lies in the fact that tomorrow's election is not, after all, a referendum on the war but a choice as to who should run the UK. On that measure, Labour is still favored over the Conservatives.

What if the predictions are wrong and the Tories do well? That will be simpler to explain. Observers will say that Blair was punished for an unpopular war -- and that Howard struck a potent nerve in the British body politic. Since their campaign has been so relentlessly focused on immigration, Tory success will be understood as proof that the UK is hostile to outsiders. Brits may not like it, but that's how they will be seen. For elections are about more than policies and programs -- they are also moments where nations say something about who they are. Next week the world will be listening.

As the new year dawns, Taiwan faces a range of external uncertainties that could impact the safety and prosperity of its people and reverberate in its politics. Here are a few key questions that could spill over into Taiwan in the year ahead. WILL THE AI BUBBLE POP? The global AI boom supported Taiwan’s significant economic expansion in 2025. Taiwan’s economy grew over 7 percent and set records for exports, imports, and trade surplus. There is a brewing debate among investors about whether the AI boom will carry forward into 2026. Skeptics warn that AI-led global equity markets are overvalued and overleveraged

An elderly mother and her daughter were found dead in Kaohsiung after having not been seen for several days, discovered only when a foul odor began to spread and drew neighbors’ attention. There have been many similar cases, but it is particularly troubling that some of the victims were excluded from the social welfare safety net because they did not meet eligibility criteria. According to media reports, the middle-aged daughter had sought help from the local borough warden. Although the warden did step in, many services were unavailable without out-of-pocket payments due to issues with eligibility, leaving the warden’s hands

Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi on Monday announced that she would dissolve parliament on Friday. Although the snap election on Feb. 8 might appear to be a domestic affair, it would have real implications for Taiwan and regional security. Whether the Takaichi-led coalition can advance a stronger security policy lies in not just gaining enough seats in parliament to pass legislation, but also in a public mandate to push forward reforms to upgrade the Japanese military. As one of Taiwan’s closest neighbors, a boost in Japan’s defense capabilities would serve as a strong deterrent to China in acting unilaterally in the

Taiwan last week finally reached a trade agreement with the US, reducing tariffs on Taiwanese goods to 15 percent, without stacking them on existing levies, from the 20 percent rate announced by US President Donald Trump’s administration in August last year. Taiwan also became the first country to secure most-favored-nation treatment for semiconductor and related suppliers under Section 232 of the US Trade Expansion Act. In return, Taiwanese chipmakers, electronics manufacturing service providers and other technology companies would invest US$250 billion in the US, while the government would provide credit guarantees of up to US$250 billion to support Taiwanese firms