Even before the bomb ripped through our Baghdad headquarters on Aug. 19 last year, taking the lives of 22 of my colleagues, the UN mission in Iraq had already become marginal to the epic crisis being played out there.

Iraq had become the center of both the US war on terror and the war between the extremes of two civilizations. The vicious terrorist attack a year ago surprised no one working for Sergio Vieira de Mello, the UN secretary general's special representative. Indeed, the UN's Iraq communications chiefs had met that morning to seek a plan to counter the intensifying perception among Iraqis that our mission was simply an adjunct of the US occupation.

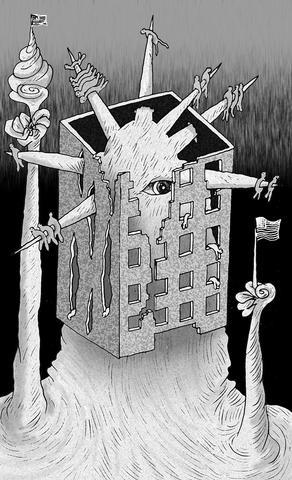

ILLUSTRATION MOUNTAIN PEOPLE

Little did the Iraqis know that the reality was quite the opposite: by August, the UN mission had grown very distant from the Americans. The intense early relationship that Sergio, the world's most brilliant negotiator of post-conflict crises, had fashioned with Paul Bremer, the US proconsul, had already fractured. Contact was intermittent once Bremer's coalition provisional authority (CPA) could deal directly with the Iraqis whom it had appointed, with Sergio's help, to the governing council. General dismay over occupation tactics aside, Sergio had already parted company with Bremer over key issues such as the need for electoral affirmation of a new constitution, and the arrests and conditions of detention of the thousands imprisoned at Abu Ghraib prison.

The low point came at the end of July last year, when, astonishingly, the US blocked the creation of a fully fledged UN mission in Iraq. Sergio believed that this mission was vital and had thought the CPA also supported it. Clearly, the Bush administration had eagerly sought a UN presence in occupied Iraq as a legitimizing factor, rather than as a partner that could mediate the occupation's early end, which we knew was essential to averting a major conflagration.

Sergio had nevertheless continued to squeeze whatever mileage he could from what he called the "constructive ambiguity" of a terrible postwar security council resolution; one that sent UN staff into the Iraqi cauldron without giving them even a minimal level of independence or authority. It is not an exaggeration to say that it was this resolution that rang the death knell for the UN in Iraq.

Having heroically resisted American pressure to authorize the war, security council members decided to show goodwill to the "victors."

"A step too far" was how an Iraqi put it to me on my second day in Baghdad.

He said that even those who had grown accustomed to the double standards the security council employed in punishing Iraqis for the 1990 invasion of Kuwait, while acquiescing to a quarter-century of Israeli occupation of Arab lands, were horrified that it could legitimize an unprovoked war that the entire world had clamorously opposed. Many Iraqis were also furious that the UN did not raise its voice against brutal occupation tactics, unaware that custom and diplomacy dictated that UN officials say little in public that would offend the world's most powerful state.

But by mid-August, a restless and discouraged Sergio had begun to breach the protocol. Two days before the bombing, he told a Brazilian journalist that Iraqis felt humiliated by the occupation, asking him how Brazilians would feel if foreign tanks were patrolling Rio de Janeiro. And on the day of the bombing, Sergio was going to issue a statement criticizing the killing by US soldiers of the Reuters cameraman Mazen Dana as he filmed an incident outside Abu Ghraib prison.

That statement saved my life. Sergio asked me to add additional information about other unlawful killings, which made me miss the 4pm meeting that was the target of that attack. Six of the seven participants were killed, and the seventh lost both legs and an arm.

Aug. 19 last year was a pivotal moment in UN history, not merely because of the unprecedented viciousness of the attack, but because of the lack of an Iraqi, Arab and Muslim outcry over the atrocity.

This near-silence exposed the depths to which the organization's standing had sunk in the Middle East as a result of its inability to contain or even condemn the militaristic excesses of US and Israeli policies in the post-Sept. 11 period. The UN is generally considered to be too willing to do the US' bidding, and its rare challenge on the Iraq war authorization was quickly forgotten once subsequent resolutions pushed the American project in Iraq. Spectacularly egregious was the security council approval of a Spanish resolution condemning ETA for the Madrid bombings when most suspected al-Qaeda.

This cavalier use of supposedly hallowed security council resolutions was only possible because of support from the US, which wished to protect the Aznar government from electoral defeat.

While the security council's double standards over the Middle East are the principal cause of Arab and Muslim hostility, US ability to pressure UN heads to toe the line is also a vexing problem. The Bush administration continues to impose maximum pressure on Kofi Annan to effect a fuller UN return to Iraq, regardless of the physical danger and moral damage to which this exposes the organization and its staff.

Annan has been resolute on the question of guaranteed security being a prerequisite for UN staff returning, but on the question of the need for a democratically elected interim government and, more recently, the composition of the interim government, it has looked as if the UN has buckled to US pressure again. When powerful member states find it necessary to give in so often to American demands, it is hardly surprising that an appointed secretary general finds it hard to challenge the US on issues it considers vital.

The Bush administration puts relentless pressure on countries to support even the most questionable aspects of its war on terror, regardless of the damage such support might do to their stability. A perfect example is the drive to get a UN mission operational in Iraq under the protection of forces from Muslim countries. Such a presence would pose excruciating risks to both the UN and any countries that comply, notably Pakistan and Saudi Arabia; but such is US power that its "persuasion" might succeed. Little seems to have been learned from the cataclysm that befell the UN a year ago today.

The UN is precious -- not because of its name, but because it struggles, however imperfectly, to reach global consensus on the world's critical issues. The fanatics who blew up the UN mission dealt a severe blow to its fortunes in the Middle East. But more lasting damage is being done to the legitimacy of this irreplaceable institution by demands to obey US dictates. If it continues to bow to pressure, its capital will be squandered and its resolutions rendered weightless for large chunks of humanity.

Member states and the secretary general should see this eroding legitimacy as the greatest challenge the organization faces. But they will be unable to make effective headway unless the US itself recognizes that it needs, in its own interest, to show greater respect for the UN, from which it can learn to define and pursue its own interests more wisely.

Salim Lone was director of communications for the UN mission in Iraq.

When it became clear that the world was entering a new era with a radical change in the US’ global stance in US President Donald Trump’s second term, many in Taiwan were concerned about what this meant for the nation’s defense against China. Instability and disruption are dangerous. Chaos introduces unknowns. There was a sense that the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) might have a point with its tendency not to trust the US. The world order is certainly changing, but concerns about the implications for Taiwan of this disruption left many blind to how the same forces might also weaken

As the new year dawns, Taiwan faces a range of external uncertainties that could impact the safety and prosperity of its people and reverberate in its politics. Here are a few key questions that could spill over into Taiwan in the year ahead. WILL THE AI BUBBLE POP? The global AI boom supported Taiwan’s significant economic expansion in 2025. Taiwan’s economy grew over 7 percent and set records for exports, imports, and trade surplus. There is a brewing debate among investors about whether the AI boom will carry forward into 2026. Skeptics warn that AI-led global equity markets are overvalued and overleveraged

Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi on Monday announced that she would dissolve parliament on Friday. Although the snap election on Feb. 8 might appear to be a domestic affair, it would have real implications for Taiwan and regional security. Whether the Takaichi-led coalition can advance a stronger security policy lies in not just gaining enough seats in parliament to pass legislation, but also in a public mandate to push forward reforms to upgrade the Japanese military. As one of Taiwan’s closest neighbors, a boost in Japan’s defense capabilities would serve as a strong deterrent to China in acting unilaterally in the

Taiwan last week finally reached a trade agreement with the US, reducing tariffs on Taiwanese goods to 15 percent, without stacking them on existing levies, from the 20 percent rate announced by US President Donald Trump’s administration in August last year. Taiwan also became the first country to secure most-favored-nation treatment for semiconductor and related suppliers under Section 232 of the US Trade Expansion Act. In return, Taiwanese chipmakers, electronics manufacturing service providers and other technology companies would invest US$250 billion in the US, while the government would provide credit guarantees of up to US$250 billion to support Taiwanese firms