I have often wondered why Karl Popper ended the dramatic peroration of the first volume of his Open Society and Its Enemies with the sentence: "We must go on into the unknown, the uncertain and insecure, using what reason we have to plan for both security and freedom." Is not freedom enough? Why put security on the same level as that supreme value?

Then one remembers that Popper was writing in the final years of World War II. Looking around the world in 2004, you begin to understand Popper's motive: Freedom always means living with risk, but without security, risk means only threats, not opportunities.

Examples abound. Things in Iraq may not be as bad as the daily news of bomb attacks make events there sound; but it is clear that there will be no lasting progress towards a liberal order in that country without basic security. Afghanistan's story is even more complex, though the same is true there. But who provides security, and how?

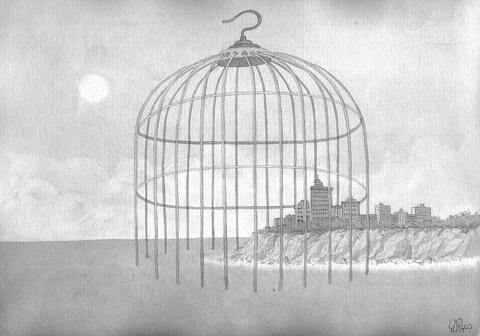

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

In Europe and the West, there is the string of terrorist acts -- from those on the US in 2001 to the pre-election bombings in Madrid -- to think about. London's mayor and police chief have jointly warned that terrorist attacks in the city are "inevitable." Almost every day there are new warnings, with heavily armed policemen in the streets, concrete barriers appearing in front of embassies and public buildings, stricter controls at airports and elsewhere -- each a daily reminder of the insecurity that surrounds us.

Nor is it only bombs that add to life's general uncertainties. Gradually, awareness is setting in that global warming is not just a gloom and doom fantasy. Social changes add to such insecurities. All at once we seem to hear two demographic time-bombs ticking: The continuing population explosion in parts of the third world, and the astonishing rate of aging in the first world. What will this mean for social policy? How will mass migration affect countries' cultural heritage?

There is also a widespread sense of economic insecurity. No sooner is an upturn announced than it falters. At any rate, employment seems to have become decoupled from growth. Millions worry about their jobs -- and thus the quality of their lives -- in addition to fearing for their personal security.

Such examples serve to show that the most disquieting aspect of today's insecurity may well be the diversity of its sources, and that there are no clear explanations and simple solutions. Even a formula like "war on terror" simplifies a more complex phenomenon.

So what should we do? Perhaps we should look at Popper again and remember his advice: To use what reason we have to tackle our insecurities.

In many cases this requires drastic measures, particularly insofar as our physical security is concerned. But while it is hard to deny that such measures are necessary, it is no less necessary to remember the other half of the phrase: "Security and freedom."

Checks on security measures that curtail the freedoms that give our lives dignity are as imperative as protection. Such checks can take many forms. One is to make all such measures temporary by giving these new laws and regulations "sunset clauses" that limit their duration. Security must not become a pretext for the suspending and destroying the liberal order.

A second requirement is that we look ahead more effectively. It is not necessary for us to wait for great catastrophes to occur if we can see them coming. Holland does not have to sink into the North Sea before we do something about the world's climate; pensions do not have to decline to near-zero before social policies are adjusted.

A third need is to preserve, and in many cases to recreate, what one might call islands of security. Globalization must become "glocalization": There is value in the relative certainties of local communities, small companies, human associations. Such islands are not sheltered and protected spaces, but models for others. They prove that up to a point security can be provided without loss of freedom.

There remains the most fundamental issue of attitude. It is debatable whether governments should ever frighten their citizens by painting the horror scenario of "inevitable" attack. The truth -- to quote Popper again -- is that "we must go on into the unknown, the uncertain and insecure," come what may.

Today's instabilities may be unusually varied and severe, but human life is one of ceaseless uncertainty at all times. Such uncertainty can lead to a frozen state of near-entropy. More frequently, uncertainty leads to someone claiming to know how to eliminate it -- frequently through arbitrary powers that benefit but a few.

False gods have always profited from a widespread sense of insecurity. Against them, an active effort to tackle the risks around us is the only answer. Perhaps we need a new Enlightenment to spread the confidence we need to live with insecurity in freedom.

Ralf Dahrendorf, author of numerous acclaimed books and a former European commissioner from Germany, is a member of the British House of Lords, a former rector of the London School of Economics and a former warden of St. Antony's College, Oxford.

Copyright: Project Syndicate/Institute for Human Sciences

There is a modern roadway stretching from central Hargeisa, the capital of Somaliland in the Horn of Africa, to the partially recognized state’s Egal International Airport. Emblazoned on a gold plaque marking the road’s inauguration in July last year, just below the flags of Somaliland and the Republic of China (ROC), is the road’s official name: “Taiwan Avenue.” The first phase of construction of the upgraded road, with new sidewalks and a modern drainage system to reduce flooding, was 70 percent funded by Taipei, which contributed US$1.85 million. That is a relatively modest sum for the effect on international perception, and

At the end of last year, a diplomatic development with consequences reaching well beyond the regional level emerged. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu declared Israel’s recognition of Somaliland as a sovereign state, paving the way for political, economic and strategic cooperation with the African nation. The diplomatic breakthrough yields, above all, substantial and tangible benefits for the two countries, enhancing Somaliland’s international posture, with a state prepared to champion its bid for broader legitimacy. With Israel’s support, Somaliland might also benefit from the expertise of Israeli companies in fields such as mineral exploration and water management, as underscored by Israeli Minister of

When former president Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) first took office in 2016, she set ambitious goals for remaking the energy mix in Taiwan. At the core of this effort was a significant expansion of the percentage of renewable energy generated to keep pace with growing domestic and global demands to reduce emissions. This effort met with broad bipartisan support as all three major parties placed expanding renewable energy at the center of their energy platforms. However, over the past several years partisanship has become a major headwind in realizing a set of energy goals that all three parties profess to want. Tsai

On Sunday, elite free solo climber Alex Honnold — famous worldwide for scaling sheer rock faces without ropes — climbed Taipei 101, once the world’s tallest building and still the most recognizable symbol of Taiwan’s modern identity. Widespread media coverage not only promoted Taiwan, but also saw the Republic of China (ROC) flag fluttering beside the building, breaking through China’s political constraints on Taiwan. That visual impact did not happen by accident. Credit belongs to Taipei 101 chairwoman Janet Chia (賈永婕), who reportedly took the extra step of replacing surrounding flags with the ROC flag ahead of the climb. Just