The search for a new managing director of the IMF provides a keen reminder of how unjust today's international institutions are. Created in the postwar world of 1945, they reflect realities that have long ceased to exist.

The organization and allocation of power in the UN, the IMF, the World Bank, and the G7 meetings reflects a global equilibrium that disappeared long ago. After World War II, Germany and Japan were the defeated aggressors, the Soviet Union posed a major threat, and China was engulfed in a civil war that would bring Mao Zedong's

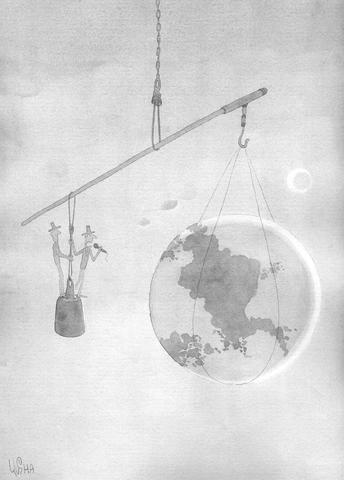

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

There were 74 independent countries in the world in 1945; today there are 193. Outside of China, Cuba and North Korea communism is popular only in West European cafes and a few US college campuses. Germany is reunited and much of the Third World is growing faster than the First World, with computer software built in Bangalore and US graduate programs, including business schools, receiving thousands of application from smart Chinese students.

The whole world has turned upside down, and yet France and the UK, for example, retain permanent seats on the UN Security Council. This made sense in 1945; it does not today. Why France and the UK and not Germany or Japan, two much larger economies? Or India and Brazil, two huge countries?

Does it really make sense that two EU member countries hold a veto power on the Security Council while the Third World (outside of China) is completely unrepre-sented? The EU does not have a common foreign policy and it will not have one in the foreseeable future, but this is no reason to continue to provide a preference to France and the UK. If Europe is really serious about a common foreign policy, does the current arrangement make any sense? True, France and the UK do have the best foreign services in Europe, but this is reversing cause and effect. France and the UK maintain this capability because they continue to have foreign-policy relevance.

Europe's over-representation extends beyond the Security Council. While a European foreign policy does not exist, Europe has some sort of common economic policy: 12 of the 15 current members have adopted the euro as their currency and share a central bank. Nevertheless Germany, France, Italy and the UK hold four of the seven seats at the G7 meetings.

Indeed, the situation is even more absurd when G7 finance ministers meet: the central bank governors of France, Germany and Italy still attend these meetings, even though their banks have been reduced to local branches of the European Central Bank, while its president -- these countries' real monetary authority -- is a mere "invited guest." Shouldn't there be only one seat for Europe?

Of course, European leaders strongly oppose any such reform: they fear losing not only important opportunities to have their photographs taken, but real power as well. But how much power they really wield in the G7 is debatable: the US president, secretaries of state and treasury, and the chairman of the US Federal Reserve almost certainly get their way more easily in a large, unwieldy group than they would in a smaller meeting where Europe spoke with a single voice.

The current search for a new IMF head continues this pattern. The IMF managing director is a post reserved for a West European; the Americans have the World Bank.

This division of jobs leaves out the developing countries, many of which are "developing" at a speed that will make them richer than Europe in per capita terms quite soon.

What about the 1 billion Indians or the 1.2 billion Chinese? Shouldn't one of them at least be considered for such a post? What about the hard-working and fast-growing South Koreans? Why should they not be represented at the same level as Italy or France? What about Latin American success stories like Chile and perhaps Mexico or Brazil?

The Europeans don't even seem to care very much about the job. After all, Horst Kuhler, the IMF managing director, resigned from a job that commands the world's attention to accept the nomination to become president of Germany, a ceremonial post with no power whatsoever, not even inside Germany.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development is located in Paris, the UN's Food and Agriculture Organization in Rome, and the list goes on. Simply put, Western Europe is overrepresented in international organizations, given its size in terms of GDP and even more so in terms of population. It is thus not surprising that some Europeans -- particularly the French -- are so reluctant to reform the international organizations, even in terms of cutting waste and inefficiency at the UN. After all, might not someone then suggest that the first step in such a reform would be to reduce Europe to a single seat on the Security Council?

Europe is being myopic. A single seat -- at the UN, the IMF or the World Bank -- would elevate Europe to the same level as the US and would augment, rather than diminish, its global influence.

The over-representation of Western Europe and the under-representation of growing de-veloping countries cannot last. Indeed, it is already creating tensions.

Obsolete dreams of grandeur should not be allowed to interfere with a realistic and fair distribution of power in the international arena.

Alberto Alesina is professor of economics at Harvard University; Francesco Giavazzi is professor of economics at Bocconi University, Milan. Their e-mail addresses are: aalesina@harvard.edu and francesco.giavazzi@uni-bocconi.it.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

Is a new foreign partner for Taiwan emerging in the Middle East? Last week, Taiwanese media reported that Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Francois Wu (吳志中) secretly visited Israel, a country with whom Taiwan has long shared unofficial relations but which has approached those relations cautiously. In the wake of China’s implicit but clear support for Hamas and Iran in the wake of the October 2023 assault on Israel, Jerusalem’s calculus may be changing. Both small countries facing literal existential threats, Israel and Taiwan have much to gain from closer ties. In his recent op-ed for the Washington Post, President William

Taiwan-India relations appear to have been put on the back burner this year, including on Taiwan’s side. Geopolitical pressures have compelled both countries to recalibrate their priorities, even as their core security challenges remain unchanged. However, what is striking is the visible decline in the attention India once received from Taiwan. The absence of the annual Diwali celebrations for the Indian community and the lack of a commemoration marking the 30-year anniversary of the representative offices, the India Taipei Association and the Taipei Economic and Cultural Center, speak volumes and raise serious questions about whether Taiwan still has a coherent India

A stabbing attack inside and near two busy Taipei MRT stations on Friday evening shocked the nation and made headlines in many foreign and local news media, as such indiscriminate attacks are rare in Taiwan. Four people died, including the 27-year-old suspect, and 11 people sustained injuries. At Taipei Main Station, the suspect threw smoke grenades near two exits and fatally stabbed one person who tried to stop him. He later made his way to Eslite Spectrum Nanxi department store near Zhongshan MRT Station, where he threw more smoke grenades and fatally stabbed a person on a scooter by the roadside.

Recent media reports have again warned that traditional Chinese medicine pharmacies are disappearing and might vanish altogether within the next 15 years. Yet viewed through the broader lens of social and economic change, the rise and fall — or transformation — of industries is rarely the result of a single factor, nor is it inherently negative. Taiwan itself offers a clear parallel. Once renowned globally for manufacturing, it is now best known for its high-tech industries. Along the way, some businesses successfully transformed, while others disappeared. These shifts, painful as they might be for those directly affected, have not necessarily harmed society