The Madrid bombings have made Europeans feel the scourge of terrorism in their bones. March 11 is now Europe's version of Sept. 11 in the US. Yet the US and Europe often do not seem to see the world through the same glasses: Spain's response to the terrorist attacks -- a threat common to all democracies -- was to vote in a government promising an end to pro-US policy on Iraq. Does this mean that Europe and the US have dramatically different visions?

Part of the seeming disconnect on foreign policy emerges from a misunderstanding about what "Europe" is about. The European project is a realist's response to globalization and its challenges. It was initiated to create "solidarites de fait," promote political stability, and consolidate democracy and Europe's social model. Having achieved these goals, Europe now wants to make a positive contribution to world developments.

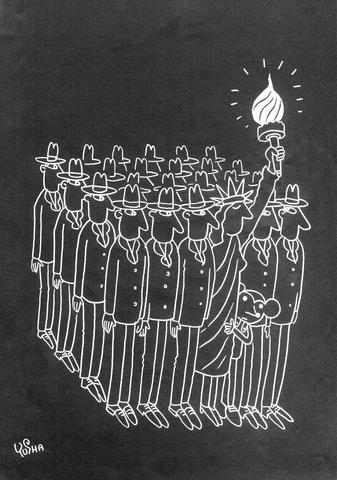

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

This is not nostalgia for past glory. An unprecedented degree of solidarity now exists across Europe, as was apparent in the collective mourning and outpouring of sympathy toward Spain; we must build on that huge potential to create a logic of solidarity in the world.

The US, also victim of a horrendous attack, feels drawn to the world, but not to promote a similar model of cooperation. Rather, in defending their values and security, Americans strive to defend the world, especially the Western world, from dark new threats. The messianic idealism that liberated Europe from Nazism and protected Western Europe from communism is now directed at other enemies.

With all the attention devoted to strained transatlantic relations, it is easy to overlook how often our preoccupations overlap. On issues such as terrorism, weapons proliferation, Iran, Afghanistan (where we jointly train the country's future army), and Africa (where French initiatives with US support recently succeeded in stabilizing the Ivory Coast and Congo), Europe and the US speak with a common voice. But on some issues, such as the Iraq war, Europeans are not all ready to follow the US blindly.

The world -- Europe in particular -- has fascination and admiration for the US. But today we must move away from fascination and gratitude and realize that the pursuit of European integration remains in the best interest of the US, which has supported it for 50 years. In today's world, there is clearly work for two to bring about stability and security, and in promoting common values.

In particular, the Franco-German "engine" of Europe should not be seen as a potential rival to the US. France and Germany are not an axis aspiring to be some sort of an alternative leadership to the US. Rather, the two countries form a laboratory needed for the internal working of the EU. Anyone who thinks we are building a European rival to the US has not looked properly at the facts.

Indeed, France and Germany do not get along naturally. Much sets us apart: EU enlargement, agriculture and domestic market issues. So it is not the sum of the two that matters, but the deal between the two, which should be viewed as a prototype of the emerging Europe. It is in that process, mostly inward looking, that France and Germany claim to make Europe advance.

So I do not believe that a lasting rift looms. Most Americans still see in Europe a partner with largely the same aims in the world. Most Europeans see in the US a strong friend. We are all allies of the US; our draft constitution restates the importance of the NATO link; our strategy for growth and our contribution to global stability depend on the irreplaceable nature of our relationship with the US.

This is why the US should encourage the development of a common European security and defense policy, which is merely the burden-sharing that the US has been pressing on Europe for decades. We must forge greater European military capacities simply to put in place a mechanism that allows us to stand effectively shoulder to shoulder when terrorism or other catastrophes strike one of our democracies, as just happened.

But we must also establish an autonomous European military planning capacity, because the EU might need to lead its own operations, perhaps because NATO is unwilling to. We French are opposed to building a "two-speed" Europe. But we want structured co-operation -- meaning that some European states may press ahead in defense capacity -- because we are not prepared to let the more cautious and hesitant dictate a recurrence of the Balkan tragedy of the 1990s, when Europeans couldn't act and the US wouldn't (for a while). The creation of such a capacity will make the EU a more effective transatlantic partner.

So it is hard for Europeans to understand why plans for closer European integration should be seen as anti-American. The only way to arrest such fears is through closer and more frequent dialogue. On defense and security matters, the EU's security doctrine provides a great opportunity to build on our common worries: terrorism and non-proliferation, but also the need to ensure sustainable development in all quarters of the world.

Europe and the US must pursue their aims in cooperation, while ensuring that such cooperation never becomes an alliance of the "West against the Rest." Some in the West have tried to conjure a "Clash of Civilizations" out of our troubled times. Our task is to find a way to stand together without standing against anybody in particular.

Noelle? Lenoir is France's minister for Europe and a former member of the Constitutional Court, France's highest court, and has taught law at Yale University and the University of London.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) challenges and ignores the international rules-based order by violating Taiwanese airspace using a high-flying drone: This incident is a multi-layered challenge, including a lawfare challenge against the First Island Chain, the US, and the world. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) defines lawfare as “controlling the enemy through the law or using the law to constrain the enemy.” Chen Yu-cheng (陳育正), an associate professor at the Graduate Institute of China Military Affairs Studies, at Taiwan’s Fu Hsing Kang College (National Defense University), argues the PLA uses lawfare to create a precedent and a new de facto legal

Chile has elected a new government that has the opportunity to take a fresh look at some key aspects of foreign economic policy, mainly a greater focus on Asia, including Taiwan. Still, in the great scheme of things, Chile is a small nation in Latin America, compared with giants such as Brazil and Mexico, or other major markets such as Colombia and Argentina. So why should Taiwan pay much attention to the new administration? Because the victory of Chilean president-elect Jose Antonio Kast, a right-of-center politician, can be seen as confirming that the continent is undergoing one of its periodic political shifts,

On Sunday, elite free solo climber Alex Honnold — famous worldwide for scaling sheer rock faces without ropes — climbed Taipei 101, once the world’s tallest building and still the most recognizable symbol of Taiwan’s modern identity. Widespread media coverage not only promoted Taiwan, but also saw the Republic of China (ROC) flag fluttering beside the building, breaking through China’s political constraints on Taiwan. That visual impact did not happen by accident. Credit belongs to Taipei 101 chairwoman Janet Chia (賈永婕), who reportedly took the extra step of replacing surrounding flags with the ROC flag ahead of the climb. Just

Taiwan’s long-term care system has fallen into a structural paradox. Staffing shortages have led to a situation in which almost 20 percent of the about 110,000 beds in the care system are vacant, but new patient admissions remain closed. Although the government’s “Long-term Care 3.0” program has increased subsidies and sought to integrate medical and elderly care systems, strict staff-to-patient ratios, a narrow labor pipeline and rising inflation-driven costs have left many small to medium-sized care centers struggling. With nearly 20,000 beds forced to remain empty as a consequence, the issue is not isolated management failures, but a far more