I was driving through up-state New York recently. In Buffalo, the huge people out on the street were sipping from giant plastic cups, while shambling about in loose tracksuits and tops decorated with the upbeat emblem of the Buffalo Bills. I stopped at a diner for breakfast, where everyone was eating generous combinations of kiddies' food: pancakes with syrup, eggs over easy or sunny side up, juice, milk, milkshakes. As the waitresses made encouraging noises it suddenly occurred to me that they were treating us exactly as if we were huge babies. And every time I watched television, the presenters -- coiffed, buffed and shining -- were speaking as if to infants, cheerfully, full of encouragement, sometimes switching to a grave demeanour for the important stuff like the non-appearance of weapons of mass destruction.

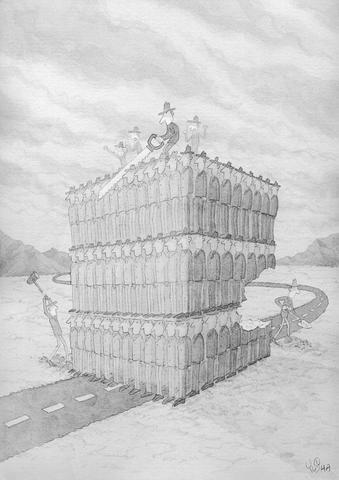

But this is not an anti-American rant, even if US President George W. Bush did find it necessary to explain what the phrase "dead or alive" meant, and even if he has promised to smoke the evil ones out of their caves. Bushisms are only one example of a phenomenon I have begun to notice everywhere: the infantilizing of the public, with the public's eager connivance. And no public is conniving more eagerly than the British public, particularly if we can accept that our own speciality, "reality" TV, means anything at all.

The puzzle, as a new book by Nick Clarke, The Shadow of a Nation: The Changing Face of Britain, asks, is why the popular mood has changed so radically from one of cautious self-restraint to a religious zeal for gratification. The demonstrable result of this change is the extraordinary number of obese people who lumber around the streets and presumably even more who stay at home because they can't lumber at all. Last week in Yorkshire, in the north of England, I was, until the eye adjusted, astounded by the size of men, women and children. But over-eating is in a sense only the obvious and visible sign of a fall from grace, a sort of perversion of the sacraments. In all sorts of ways we act as if there are no consequences.

How has this come about? In 1937, Walt Disney produced Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. With hindsight, this may have been a very significant moment. Bruno Bettelheim, a survivor of the Holocaust, the darkest imaginable horror, said the message of fairy tales is that struggles against severe difficulties in life are unavoidable.

Although fairy tales simplify the moral problems and provide improbable solutions in the form of tasks and magical tools, these tales once contained dark and unpalatable truths, mortality being the best example. But with Snow White, Disney produced the happy fairy tale: the unpleasantness of life was expunged: the wicked stepmother was not required to dance in red-hot iron shoes. Instead, hard work, a good attitude and cheerful demeanour were shown to triumph over the irrational.

In subsequent animations, the magic became a sort of lifestyle accessory. Nobody had chunks of their head used as an ingredient of soup, or their fingers cut off; in fact they were not required to confront death at all. And it is a consistent feature of the new infantilism that there are no consequences. The Iraq war, from "Shock and Awe" to "Saving Private Jessica Lynch", demonstrated that the unpleasantness of battle can be expunged and can be largely painless for those with the technology -- in other words, exactly like a video game. But of course there have been consequences, and we are likely to feel the force of them in the near future.

Infantilism comes in many guises: the belief that we have guardian angels, the idea that our laptop loves us, the matey messages from Internet sellers, the mission statements of banks, the reality TV shows, the cups with baby-bottle nozzles, the bogus promises of skinny lattes and bran muffins, and phone-in and interactive programs, to list just an obvious few. Not so obviously childish are the political messages. Politicians have understood that we live in a new romantic age because we, the public, have come to believe that the only unit of currency that can be trusted is the self.

In politics, this means there are no hard choices. Instead there is a sort of low-level spirituality: the fraud lies in the implication that society is becoming more caring. The word resounds emptily all over the country. Pedophiles are being caught, wife-beaters are going on a register, bus and cycle lanes are sprouting, foxes are being protected, criminal immigrants are being deported, countless league tables are being drawn up. All the while large areas of education, transport, public behavior and hospitals are -- as we can all see -- under siege. And cycle lanes appear to have no purpose other than the symbolic. But the important thing is the self.

The self cannot be required to practise critical self-examination on its progress through life; instead the self is seen as being on a journey of improvement. Fundamentalism, too, is a kind of infantilism. Although it pretends to subsume the individual into a greater truth, it is in a sense the mirror image of the promotion of the self: It provides a simple, infantile, answer to the world's problems. Just as fairy tales simplify the moral choices, and religions codify them, so fundamentalism discounts liberal democracy and human rights. In contemporary society it also provides an identity: look, I have discovered truth and certainty, while you are still groping about in a kind of moral swamp. And from this certainty, as history has shown, consequences inevitably follow.

Still, I have come to the conclusion that dumbing-down, most often linked to television, is not the real problem. The problem is a society that has no confidence in attributing value: hence the resort to self-indulgence and infantile behavior; hence the infantile political solutions and the infantile commercial promises. It's a kind of make-believe because we don't know what our values are. But in the same way that we know gross indulgence leads to health problems so we know in our hearts the result of this infantilism: there will be tears before bed-time.

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s