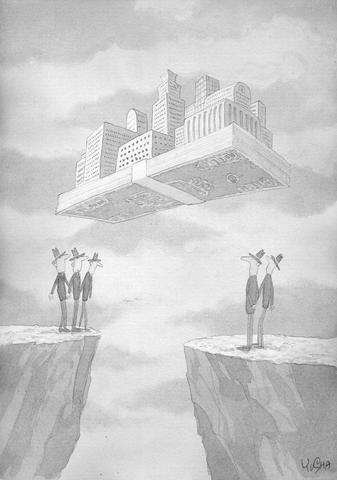

The UN and NATO are widely perceived as damaged, if not broken, by their failure to agree on what to do about Iraq. Will these cracks in the international political system now wound the world's economic architecture, and with it globalization, as well?

International economic agreements have never been easy to make. Reaching consensus among the WTO's 145 members, where one dissent can cause utter disarray, was difficult even before the world's governments divided into pro- and anti-American camps. Indeed, multilateral trade agreements were being eclipsed by bilateral deals, such as between the EU and various developing countries, long before the divisions over Iraq appeared.

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

Of course, the problem goes deeper and not everything that touches globalization has turned dark. Immigration controls, for example, have been relaxed in several European countries (notably Germany) due to declining populations and educational shortcomings. But bad economic times are rarely moments when governments push bold international economic proposals.

Economic fragility among the world's leading economies is the biggest stumbling block. The US and the EU have few fiscal and monetary levers left to combat weak performance. Short-term interest rates in the US, at 1.25 percent, are at a 40-year low. The US Congress has pared US$100 billion from the Bush administration's 10-year US$726 billion tax cut plan and the US's projected 10-year US$2 trillion budget deficit will grow as the Iraq war's costs mount, with President George W. Bush submitting a supplemental request for US$80 billion (0.8 percent of GDP) in extra military spending this year.

Such spending risks absorb productive resources that could be employed more efficiently elsewhere. This was demonstrated by the rapid growth of output and incomes that followed the arrival of the so-called "peace dividend" which came with the Cold War's end. Moreover, others (Arab countries, Germany, and Japan) will not cover the US' military costs, as in the 1991 Gulf War. We are now back to the more usual situation where war is financed by government debt, which burdens future generations unless it is eroded by inflation.

In the Eurozone the scope for fiscal stimulus (lower taxes and/or higher public spending) was constrained until war blew a hole in the Stability Pact, which caps member budget deficits at 3 percent of GDP. The limit will now be relaxed due to the "exceptional" circumstances implied by the Iraq war-providing relief, ironically, to the war's main European opponents, France and Germany. But the European Central Bank remains reluctant to ease monetary policy.

In Japan, there seems little hope that the world's second-largest economy can extricate itself from its homemade deflation trap to generate the demand needed to offset economic weakness elsewhere in the world. Four years of deflation and a drawn-out banking crisis offer little prospect of economic stimulus. Higher oil prices and lower trade turnover aggravate the problem.

But high oil prices threaten the health of the entire US$45 trillion world economy. Oil prices have flirted with their highest level since the Gulf War and will go higher if Iraq's oil infrastructure (or that of neighboring countries) is damaged.

The adverse effects on growth will be felt everywhere, but nowhere more, perhaps, than in the energy-dependent South Korea and China. Although China's official growth rate reached 8 percent last year, its high budget deficit and large stock of non-performing loans (about 40 percent of GDP) mean that it cannot afford any slowdown if it is to keep people employed, especially in rural areas.

Some poor economies will be directly damaged by the loss of the Iraq market, which accounts for roughly 40 percent of Vietnam's tea exports and 20 percent of its rice exports. For others, weakness in the world's big economies may be compounded by political risks.

Turkey has suffered from rising oil prices, falling tourism income (its second-largest source of foreign exchange), and declining foreign investment. Now the Erdogan government's lukewarm support for US policy on Iraq exposes Turkey to doubts about America's commitment to its economic well being, and global markets may question its ability to service its US$100 billion public-sector debt this year and next.

The test of whether multilateral cooperation can be put back on track, and reconciled with America's war against terrorism and the spread of weapons of mass destruction, may come with Iraq's reconstruction. With the costs of ousting Iraqi President Saddam Hussein and occupying Iraq likely to run at anywhere from US$100 to US$600 billion over the next decade, the US will want to "internationalize" Iraq's reconstruction.

Iraq's US$20 billion annual oil revenues cannot meet such costs. Indeed, those revenues will scarcely cover the costs of rebuilding basic infrastructure, feeding and housing displaced populations, and paying for the country's civil administration.

After the ouster of the Taliban last year, the US$4.5 billion of reconstruction aid pledged to Afghanistan's new government demonstrated that a multilateral approach to reconstruction is possible. But the poisoned atmosphere that followed the UN debates on Iraq may prevent the US from getting its way here. Already, French President Jacques Chirac has promised to veto any UN Security Council resolution on reconstruction that seeks to justify the war. If the world economy is to recover, the diplomatic failures and name-calling must end.

Brigitte Granville is the head of the International Economics Program at the Royal Institute for International Affairs, London.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

Jaw Shaw-kong (趙少康), former chairman of Broadcasting Corp of China and leader of the “blue fighters,” recently announced that he had canned his trip to east Africa, and he would stay in Taiwan for the recall vote on Saturday. He added that he hoped “his friends in the blue camp would follow his lead.” His statement is quite interesting for a few reasons. Jaw had been criticized following media reports that he would be traveling in east Africa during the recall vote. While he decided to stay in Taiwan after drawing a lot of flak, his hesitation says it all: If

When Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) caucus whip Ker Chien-ming (柯建銘) first suggested a mass recall of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislators, the Taipei Times called the idea “not only absurd, but also deeply undemocratic” (“Lai’s speech and legislative chaos,” Jan. 6, page 8). In a subsequent editorial (“Recall chaos plays into KMT hands,” Jan. 9, page 8), the paper wrote that his suggestion was not a solution, and that if it failed, it would exacerbate the enmity between the parties and lead to a cascade of revenge recalls. The danger came from having the DPP orchestrate a mass recall. As it transpired,

Much has been said about the significance of the recall vote, but here is what must be said clearly and without euphemism: This vote is not just about legislative misconduct. It is about defending Taiwan’s sovereignty against a “united front” campaign that has crept into the heart of our legislature. Taiwanese voters on Jan. 13 last year made a complex decision. Many supported William Lai (賴清德) for president to keep Taiwan strong on the world stage. At the same time, some hoped that giving the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) a legislative majority would offer a

Owing to the combined majority of the opposition Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), the legislature last week voted to further extend the current session to the end of next month, prolonging the session twice for a total of 211 days, the longest in Taiwan’s democratic history. Legally, the legislature holds two regular sessions annually: from February to May, and from September to December. The extensions pushed by the opposition in May and last week mean there would be no break between the first and second sessions this year. While the opposition parties said the extensions were needed to