People tend to think of work-family conflict as something that only women experience and assume that it pushes women to quit their jobs.

However, new research shows that men feel it just as much as women do and that it also undercuts their commitment to their employer.

An article published this week in Harvard Business Review looks at why both men and women feel work-family conflict, but why men’s feelings on this remain largely invisible.

The authors, Robin Ely of Harvard Business School and Irene Padavic at Florida State University, studied a global consulting firm for 18 months.

In interviews with the research team, which also included Erin Reid of McMaster University, the men expressed profound sadness and guilt over not being there for their children and their partners.

It is not the only study to reveal that men feel work-family conflict — but it is remarkable for the portrait it paints of silent male suffering, and the way in which male silence and female openness conspire to maintain the status quo.

One working dad painted a bleak portrait of his son playing alone with a toy train, while a nanny looked coldly on. Another seemed sad that his young daughter always asked for his wife at bedtime — never for him.

Yet while these men felt work-family conflict deeply, they also tended to suppress those feelings — minimizing their own feelings or displacing them onto women.

One described falling “chemically, deeply” in love with his newborn daughter and said that it helped him “understand” why some women would not want to go back to work after having kids.

His takeaway was not that he was entitled to his own mixed feelings, but that women must have a hard time balancing work and family.

Others distanced themselves from their fears using humor, or by emphasizing that however bad they had felt before, they felt better now — now that they are not on a six-month assignment in a foreign country, now that only one of their kids cries when they leave for work, now that the seven-year-old can “almost” make his own breakfast (Pop Tarts).

By contrast, the women were more frank about the work-family conflicts they felt. They did not hide from them, or project them onto someone else.

The women were also more likely to take action to try to resolve the conflict, like swapping a client-facing role for one with more-predictable hours. As a result, though, the women gave up power in the firm — and saw their progress stall.

Women made up 37 percent of junior associates, but only 10 percent of partners; and women who made it to partner took two years longer to get there than men did.

While senior leaders assumed it was women who struggled with the firm’s 24-7 culture, men and women reported equally that the relentless pace was crushing — and unnecessary.

Consultants spoke of working through the night to make 100-slide presentations they were all too aware the client could not use, had not asked for and probably would not even read, but no one at the firm seemed to think it was possible to stop producing them.

If it sounds a little like a cult, that is because it kind of is — in which work is a kind of religion and devotees show their faith not by shaving their heads or wearing hair shirts, but by working all the time.

Men made it clear that working this way took a toll on their commitment to the firm.

One dad said he “wanted to quit then and there” when work caused him to miss his son’s soccer game — and his son to burst into tears.

Another said he was “overworked and underfamilied,” adding: “If I were a betting man, I’d bet that a year from now I’m working somewhere else.”

That was what happened. In fact, while the firm assumed women had a higher turnover rate, this was not true — looking at three years of data showed men were just as likely to quit as women.

Nonetheless, when the researchers presented their findings to the firm’s leaders — that the culture of overwork was hurting both men and women, but that women were paying a disproportionate price for it — the managers rejected the conclusion as well as the proposed gender-neutral solutions.

They said that work-family conflict was women’s problem, and that any solution must target women specifically. (Since female-specific solutions only seem to derail women’s careers, adding yet another was not likely to help.)

We cannot keep pretending, in the face of mounting evidence, that work-family conflict is only a woman’s problem, or that the only reason more women are not working 24-7 is because of their children.

It is closer to the truth to say that no one wants to work 24-7, because it is, frankly, a miserable way to live.

Instead of offering women yet more poisoned chalices in the form of flex-time programs that only mark them for punishment, managers must target dysfunctional work cultures that hinge on over-selling and over-delivering, driving both men and women to seek other employment arrangements.

Talented, hard-working people have options. They also, quite frequently, exercise them.

Sarah Green Carmichael is an editor with Bloomberg Opinion. She was managing editor of ideas and commentary at Barron’s and an executive editor at Harvard Business Review, where she hosted the HBR Ideacast.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

In Italy’s storied gold-making hubs, jewelers are reworking their designs to trim gold content as they race to blunt the effect of record prices and appeal to shoppers watching their budgets. Gold prices hit a record high on Thursday, surging near US$5,600 an ounce, more than double a year ago as geopolitical concerns and jitters over trade pushed investors toward the safe-haven asset. The rally is putting undue pressure on small artisans as they face mounting demands from customers, including international brands, to produce cheaper items, from signature pieces to wedding rings, according to interviews with four independent jewelers in Italy’s main

Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi has talked up the benefits of a weaker yen in a campaign speech, adopting a tone at odds with her finance ministry, which has refused to rule out any options to counter excessive foreign exchange volatility. Takaichi later softened her stance, saying she did not have a preference for the yen’s direction. “People say the weak yen is bad right now, but for export industries, it’s a major opportunity,” Takaichi said on Saturday at a rally for Liberal Democratic Party candidate Daishiro Yamagiwa in Kanagawa Prefecture ahead of a snap election on Sunday. “Whether it’s selling food or

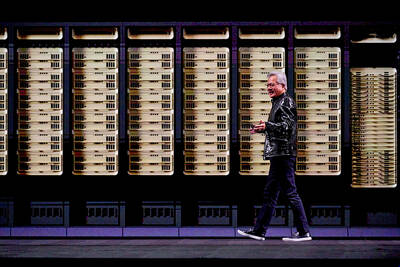

CONCERNS: Tech companies investing in AI businesses that purchase their products have raised questions among investors that they are artificially propping up demand Nvidia Corp chief executive officer Jensen Huang (黃仁勳) on Saturday said that the company would be participating in OpenAI’s latest funding round, describing it as potentially “the largest investment we’ve ever made.” “We will invest a great deal of money,” Huang told reporters while visiting Taipei. “I believe in OpenAI. The work that they do is incredible. They’re one of the most consequential companies of our time.” Huang did not say exactly how much Nvidia might contribute, but described the investment as “huge.” “Let Sam announce how much he’s going to raise — it’s for him to decide,” Huang said, referring to OpenAI

The global server market is expected to grow 12.8 percent annually this year, with artificial intelligence (AI) servers projected to account for 16.5 percent, driven by continued investment in AI infrastructure by major cloud service providers (CSPs), market researcher TrendForce Corp (集邦科技) said yesterday. Global AI server shipments this year are expected to increase 28 percent year-on-year to more than 2.7 million units, driven by sustained demand from CSPs and government sovereign cloud projects, TrendForce analyst Frank Kung (龔明德) told the Taipei Times. Demand for GPU-based AI servers, including Nvidia Corp’s GB and Vera Rubin rack systems, is expected to remain high,