Braving the snow and cold, 18-year-old Abrar Ahmad is one of thousands of Kashmiris who regularly spend hours traveling on a packed train just so that they can go online as the region grapples with the longest Internet blackout imposed by a democracy.

Stepping off the crammed train — dubbed the “Internet Express” by Indian Kashmiris — in the nearby town of Banihal, the passengers make a beeline for cafes where they pay up to 300 rupees (US$4.22) for an hour of broadband access.

“I couldn’t have afforded to miss this opportunity,” Ahmad told the Thomson Reuters Foundation after filling out an online job application at a teeming Internet cafe, where dozens of others hit by the five-and-a-half-month Internet shutdown lined up behind him.

“There is no one else in my family to take care of my three younger siblings and me,” he said, adding that his father, a mason, lost his leg in a road accident last year.

Indian-administered Kashmir has been without broadband and mobile data services since Aug. 5 last year, when India’s government revoked the special status of its only Muslim-majority state, splitting Jammu & Kashmir in two.

Despite a UN declaration in 2016 that the Internet is a human right, shutdowns have risen in the past few years as governments from the Philippines to Yemen have said that they were necessary for public safety and national security.

Kashmir is claimed in full by India and Pakistan, which have gone to war twice over it. Each rules parts of the scenic Himalayan region.

India said that it cut communications to prevent unrest in Kashmir, where a separatist insurgency has killed more than 40,000 people since 1989.

The lockdown has cost Kashmir more than US$2.4 billion since August, with sectors directly dependent on the Internet such as e-commerce and information technology the worst-hit, the Kashmir Chamber of Commerce and Industry said.

“Doing trade without the Internet is unimaginable in the present-day world,” said Abdul Majeed Mir, vice president of the chamber, which estimated that nearly 500,000 jobs have been lost. “Irreversible damage has been caused to the economy.”

Kashmir’s Internet ban has affected everything from relationships to access to healthcare, said Raman Jit Singh Chima, Asia policy director at global digital rights group Access Now.

In addition to introducing the democratic world’s longest Internet clampdown in Kashmir, Access Now said that India also accounted for two-thirds of global shutdowns in 2018.

“Punishing an entire population on the basis of saying potential violence or terrorism might occur is extraordinary,” Chima said.

The Indian home and information ministries did not respond to requests for comment.

At a noisy cybercafe in Banihal, Danish stepped out to catch his breath as people elbowed past to get on the Web. Diesel generator fumes filled the cramped space to keep computers and laptops running during frequent power cuts.

“I felt suffocated inside,” said Danish, a University of Kashmir academic who declined to give his full name. “This Internet gag is driving me crazy.”

However, he prefers the lengthy trek to Banihal to trying to get online at one of the hundreds of Internet kiosks the government has set up in Kashmir, where demand hugely outstrips supply.

New Delhi said that the scrapping of Jammu & Kashmir’s special status was necessary to integrate it into the rest of India and spur development.

It has done anything but that, locals said.

Outside a courier company in Kashmir’s main city, Srinagar, two delivery executives chatted idly by a bonfire, saying that no Internet meant no packages.

“We are the only two who still come to the office. Some 50 boys have lost their jobs,” Touseef Ahmad said. “If the Internet is not restored soon, I can lose my job.”

Tourism — for decades the backbone of the scenic region’s economy — has been badly hit.

Every year, people from across India flock to Kashmir to enjoy its snowcapped mountains and scenic Dal Lake, home to hundreds of ornately-carved houseboats whose owners rely on tourism.

Kashmiri boat association president Bashir Ahmad Sultani said that there was no work for more than 4,000 boatmen.

“We are going through very bad times. Some of us are not even able to arrange two square meals for our families,” boatman Mohammad Shafi said. “We are looking at a dark future.”

The restriction has served a major blow to tour operators, hoteliers and artisans, as well.

“I mostly buy things on credit from local shopkeepers,” said Ghulam Jeelani, a hotel manager in Srinagar, who feared being laid off with no online bookings or transactions.

The 52-year-old said that he has been struggling to pay for his daughter’s tuition and daily groceries since his monthly salary was slashed by three-fourths to 6,000 rupees in October last year.

“I have been told that I can’t get even this amount if tourists don’t start arriving in a few weeks,” he added.

The government has not said when Internet access will be restored, despite calls from civil society and the UN.

Without it, many locals have said that they might have to take up manual jobs such as construction — or even pack up and leave.

However, for Danish, frequent trips to Banihal are the only way forward.

“I would have moved to some other city, but I can’t, because my [supervising] professor is in Kashmir. How can I exchange e-mails with him when there is no Internet?” he said. “Such a long blackout ... amounts to playing with our future. We are losing precious time.”

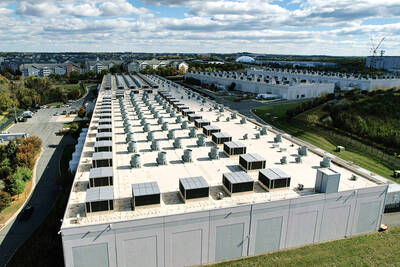

The demise of the coal industry left the US’ Appalachian region in tatters, with lost jobs, spoiled water and countless kilometers of abandoned underground mines. Now entrepreneurs are eyeing the rural region with ambitious visions to rebuild its economy by converting old mines into solar power systems and data centers that could help fuel the increasing power demands of the artificial intelligence (AI) boom. One such project is underway by a non-profit team calling itself Energy DELTA (Discovery, Education, Learning and Technology Accelerator) Lab, which is looking to develop energy sources on about 26,305 hectares of old coal land in

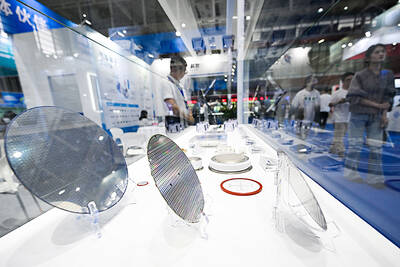

Taiwan’s exports soared 56 percent year-on-year to an all-time high of US$64.05 billion last month, propelled by surging global demand for artificial intelligence (AI), high-performance computing and cloud service infrastructure, the Ministry of Finance said yesterday. Department of Statistics Director-General Beatrice Tsai (蔡美娜) called the figure an unexpected upside surprise, citing a wave of technology orders from overseas customers alongside the usual year-end shopping season for technology products. Growth is likely to remain strong this month, she said, projecting a 40 percent to 45 percent expansion on an annual basis. The outperformance could prompt the Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and

Netflix on Friday faced fierce criticism over its blockbuster deal to acquire Warner Bros Discovery. The streaming giant is already viewed as a pariah in some Hollywood circles, largely due to its reluctance to release content in theaters and its disruption of traditional industry practices. As Netflix emerged as the likely winning bidder for Warner Bros — the studio behind Casablanca, the Harry Potter movies and Friends — Hollywood’s elite launched an aggressive campaign against the acquisition. Titanic director James Cameron called the buyout a “disaster,” while a group of prominent producers are lobbying US Congress to oppose the deal,

Two Chinese chipmakers are attracting strong retail investor demand, buoyed by industry peer Moore Threads Technology Co’s (摩爾線程) stellar debut. The retail portion of MetaX Integrated Circuits (Shanghai) Co’s (上海沐曦) upcoming initial public offering (IPO) was 2,986 times oversubscribed on Friday, according to a filing. Meanwhile, Beijing Onmicro Electronics Co (北京昂瑞微), which makes radio frequency chips, was 2,899 times oversubscribed on Friday, its filing showed. The bids coincided with Moore Threads’ trading debut, which surged 425 percent on Friday after raising 8 billion yuan (US$1.13 billion) on bets that the company could emerge as a viable local competitor to Nvidia